Scheduled for the 23rd of November 2019 after having been delayed twice the referendum of Bougainville was on all lips when we visited the region on our last tour of Papua New Guinea. You might not have heard of Bougainville and might have even less heard of its referendum, so what is it about and what are the stakes?

A troubled past

Bougainville has been nicknamed the island of tears for its recent tragic history. All of it starts in 1885 when the island, along with a big part of Papua and the Northern Solomon, was ruled by German colonialists. It is the first time when the territory of Bougainville was stuck together with the rest of what would become Papua New Guinea, as in many other places in the world, by arbitrary lines drawn by colonial powers. After the defeat of the Germans in World War II, the whole region fell under Australian administration. It later fell under Japanese occupation and finally, was grouped with Papua New Guinea when that country gained independence in 1975. Throughout all that time and all those administrations, the Bougainvillians, feeling different from the Papua New Guineas and closer to the culture of the Solomon Islanders, were never asked what they wanted. To this day, it is quite easy to spot a Bougainvillian amongst other Papua New Guinean as the Bougainvillians generally have a much darker skin. Although nowadays this dark skin is often a subject of pride for the people of Bougainville, which can often be seen wearing t-shirts with slogans such as “Black is beautiful” or “Bougainville, the black island”, this physical difference would have tragic repercussions in the year to come.

The spark that set everything ablaze

The Panguna Mine – The largest mineral exploitation while it was open

Installations at the Panguna mine are now defunct

For a long time, Bougainvillians and Papua New Guineans coexisted and worked together on the island. Bougainville does not have a very varied economy and its resources can be quite limited apart from fishing and some tropical crops. However, the Bougainvillians sit on a massive mineral wealth. The Panguna mine, in the centre of the island, is one of the largest reserve of both copper and gold in PNG but also in the world. It exploitation started in 1972, with most of the mineral extracted being sold to Australia. At the peak of its exploitation, the mine’s products made up for 45% of Papua New Guinea’s export revenue, with the government of the country holding 20% of the shares of the mine. In the meantime, local landowners only saw around 1.25% of the revenue come back to them. The rest of the profits was sent to the Australian mining company Conzinc Rio Tinto.

Local landowners complained that they were getting a risible share of the profit while getting the brunt of the consequences of the exploitation. They complained, notably, of terrible environmental impact, with the nearby river poisoned by the copper, causing birth defects and also of a discrimination system based on race being established on their island, with the white-skinned Australian owners on top, the mainland PNGers (nicknamed red-skins) in the middle and the local black-skinned Bougainvillians at the bottom. Tensions grew and in 1988, the conflict shifted into a global insurgency on the island opposing the forces of the Papua New Guinea government, helped by Australia and the Bougainville Revolutionary Army, composed of rebels. The mine was taken over by the BRA and closed. To this day, the mine hasn’t reopened and is left in a state of disuse. In 1990, the leader of the BRA, Francis Ona, unilaterally declared the independence of the island under the name of the kingdom of Meekamui and the conflict went on for over 20 years, with the island put under a blockade and a vicious war going on. In this war, families were torn apart as Bougainvillians picked their side between the Revolutionary and the Resistance (those who sided with the PNG government). The fights were atrocious, with the local fighters acquiring weapons as they could, including reusing WWII relics to fight, and the PNG government hiring mercenary forces to tame the rebellion.

An end to the conflict

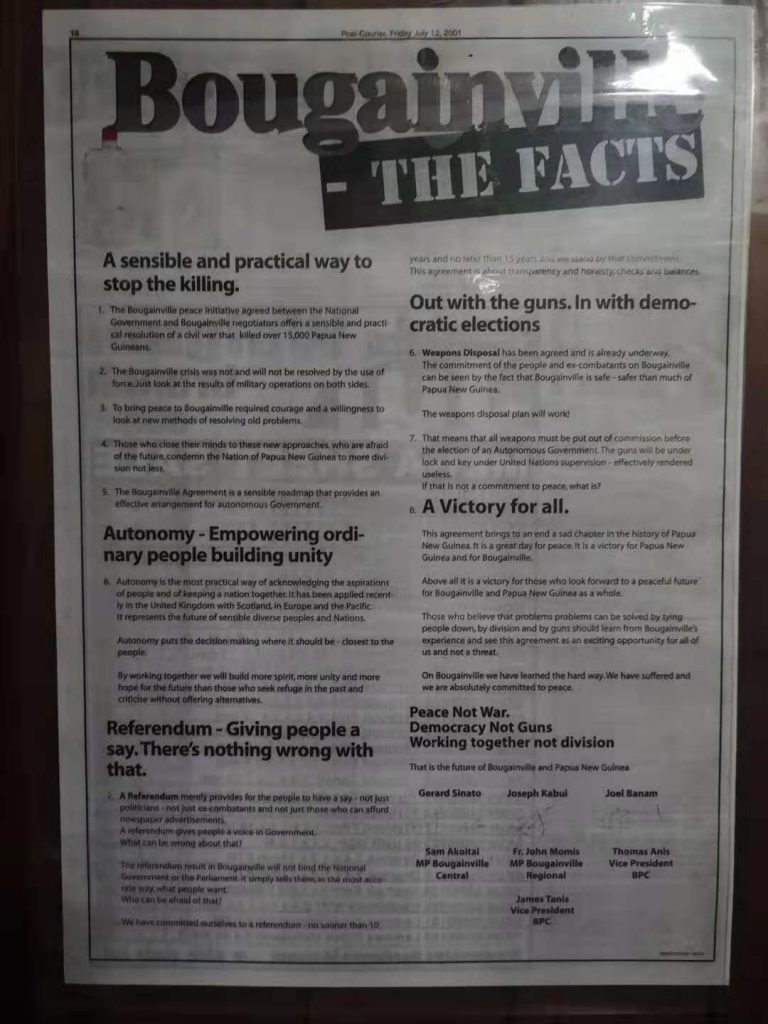

The conflict went on until 1997 when the Prime Minister at the time negotiated a ceasefire with the local insurgent leaders which led to what is called the Bougainville Peace Agreement. As a result of this agreement, a referendum to decide of the future of Bougainville was agreed upon and Bougainville was declared an Autonomous Region of Papua New Guinea. It was decided that the referendum should happen not earlier than 15 years and in no longer than 20 years. Finally, it was decided that the referendum would happen on the 23rd of November 2019. Bougainville became a Autonomous Region of Papua New Guinea and was put under a transitional government. The leader of said transitional government, President Monis, has described the Bougainville Civil War as the largest conflict in Oceania since WWII.

The shape of the referendum

Rather than a yes, no question, the referendum will ask Bougainvillians the following question and offer them two answers:

Do you agree for Bougainville to have: (1) Greater Autonomy (2) Independence?

It is important to know that the referendum is also only consultative and that the government of Papua New Guinea, once it has collected the answer, is free to do whatever it wants with it. The actual specifics of an independent Bougainville, or the procedure behind the accession to independence for the region, are not set in stone. However, Bougainville could become the youngest country in the world. Polling stations have been prepared across Bougainville and in other parts of Papua New Guinea and a team from the UN has been dispatch to oversee the process as the Bougainville Referendum Commission.

The current attitude to the referendum

On the island, the referendum is on all lips with a multitude of colourful shirts with slogans being sold to the locals. Traditional dances are paired with songs wishing “Goodbye PNG, hello referendum” and for many people who we have asked questions to, the referendum is the answer to many of Bougainville woes. Once Bougainville is independent, we were told, the mine can be reopened on good terms for the Bougainvillians and relaunch the economy. Once Bougainville is independent, the cities of the island, Arawa and Buka, which have been torched down during the conflict, can be rebuilt. Other people, however, was showing concern that, while most people agree on independence, few actually know how it would happen. Also, while it can be said that most people on the islands are for independence, Bougainvillians leaving in the rest of PNG, which are also allowed to vote, could massively vote for “Greater Autonomy”.

People are also worried that, if the Greater Autonomy option is the one that wins, fighters might take up their weapons again. While it was agreed with the ceasefire that Bougainville fighters would disarm, it is said that many people have surrendered their improvised weapon but that the good ones, the military grade firearms, have only been hidden.

Nothing is certain concerning the referendum of Bougainville, but it is certainly a fascinating era for the Pacific. Loving Bougainville and Papua New Guinea ourselves, YPT is sure to follow the events very closely.