Introduction

Director William Friedkin’s (The French Connection, Cruising) 1973 adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s book,The Exorcist, is regarded by many not only as one of the best horror films ever made but perhaps the scariest film of all time. As with all classics, the story behind the production of the film itself has taken on mythic qualities. The so-called “Exorcist Curse” has been the subject of numerous books, podcasts and documentaries, and has been most recently explored on an episode of Shudder’s popular Cursed Films series.

When one examines all of the strange occurrences that took place during pre-production, production, post-production and the release of the film, it certainly begs the question as to whether there were satanic forces at play. These events include:

• A major fire to the studio caused a delay to the start of production. Most of the sets were destroyed in the fire with the exception of that of the room of the possessed character, Reagan.

• Supporting actor Max von Sydow’s brother passed away on the first day of principal photography.

• A Jesuit priest was at one point brought in to bless the set.

• Actors Jack MacGowran and Vasiliki Maliaros died while the film was in post-production. The kicker? Both of their characters died in the film itself.

• Actress Ellen Burstyn was seriously injured in a scene where she is thrown to the ground by her possessed daughter, and the injury hurts her to this day. Although, it is worth noting that director William Friedkin, known for his unorthodox methods of directing, such as firing guns on set to startle actors, instructed the rigging team to be deliberately rough with Burstyn.

• Actress Linda Blair, too, was injured when the rigging used to make her appear to thrash around at the hands of demonic forces did the job too convincingly.

• Mercedes McCambridge, who played the voice of the demon Pazuzu, later suffered a horrific tragedy when her son killed his wife, kids and then himself.

• Upon the film’s release, there were instances of people passing out in theatres and injuring themselves, resulting in lawsuits against the Warner Brothers Pictures. Some of these incidents, however, were later revealed to be part of a deliberate PR campaign which included spreading rumors that playing the film invited demons into the theater, that it would be too upsetting an experience for pregnant women, as well as accounts of audience members vomiting and parking ambulances outside of theaters.

• A major storm in Rome on the night of its Italian premiere.

• A real radiology team was used for the scene where Reagan undergoes a radiology exam. One of the team members, a technician named Paul Batesman, was later convicted of the 1977 murder of Variety reporter Addison Verrill.

The Curse

In the recent Shudder documentary, Leap of Faith: William Friedkin on The Exorcist, Friedkin gave a small nod to the alleged “curse,” saying: “I feel to this day there were forces beyond me that brought things to that movie. Like, offerings…Fate.”

While all of these various odd and tragic coincidences make for a compelling urban legend, it seems that the best explanation that anyone can come up with for the curse is the subject matter. Cursed Films’ episode on the subject points out that the story’s demon, Pazuzu, is a Messapotamian demon that originates from Northern Iraq, but it stops short of suggesting that actually filming in a demon’s backyard could have brought on the curse! Not only was Pazuzu a demon of ancient Messapotamiun religion, he was known as the king of the demons of the wind and is said to have also brought storms and drought.

Pictured Above: Bronze Statuette of Pazuzu, Cira 8th Century BC

In Friedkin’s quest to tell a “straight ahead story that was done as realistically as possible,” he demanded to incredulous Warner Bros. executives that the film’s exteriors be shot on location such as New York City, Georgetown and Iraq. As a film like The Exorcist had never been made before, the studio executives ultimately gave in to Friedkin’s creative demands. Instead of having to shoot California’s Mojave Desert for Iraq, he was able to actually shoot in Hatra, an ancient city 68 miles southwest of Mosul in Northern Iraq.

“We [had] to open in Iraq,” says Friedkin in Leap of Faith. “That opening chapter started my skin crawling when I read it and I didn’t know why. I’m sure a lot of people to this day are puzzled. What the hell is that? But to me, it is the introduction and the solid underpinning of the piece.”

Filming on location in Northern Iraq was not without its challenges. In addition to only being able to film for 6 hours a day due to the extreme desert heat and winds, the crew were affected by numerous illnesses throughout the shoot. Additionally, Friedkin was also not able to watch his dailies. Instead, he had to rely solely on feedback from the film lab who could only report on how the footage looked over once-a-week phone calls. The political situation in Iraq, too, caused complications when, on the third week of production, the American crew were confined to their tents. Though they were assured that the problem had nothing to do with them, the atmosphere was tense.

For a bit of historical context, the Iraqi Ba’ath Party had only been in full control of the country since 1968’s July 14 Revolution and the political situation was still volatile. On June 30, 1973, when Ba’athist president Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr was due to return from a trip to Bulgaria and Poland, he was saved from assassination when his flight was delayed several hours, causing a hit sqaud waiting for him at Baghdad airport to turn themselves in thinking their plot had been foiled. The attempted coup had been led by Col. Nazem Kazzar, then-director of Iraq’s national public security department. In the ensuing chaos, Kazzar had escaped to Northern Iraq, close to where Friedkin was shooting. Filming resumed a few days later after Kazzar was apprehended and he, along with 22 other members of the “Kazzar Clique,” were executed. (al-Bakr was later usurped by his vice president Saddam Hussein)

Political unrest, weather and hygienic conditions aside, there is a truly authentic atmosphere in the film’s opening which would have never been possible on a set in the United States (see the stark difference between The Exorcist‘s scenes in Iraq and Exorcist II: The Heretic‘s scenes in “Ethiopia”). It is the small details, such as the actual bazaar through which father Merrin passes, or the real muslim prayer heard in the film’s opening; all of which help to sell what Friedkin called “the atmosphere of dread and an ancient supernatural mystery…”

At the time, there was a german archeologist overseeing a dig in Hatra. Friedkin met with the archaeologist and asked if they could film on his live dig. The archeologist agreed and the opening shots of Max von Sydow’s character, Father Merrin, walking through an excavation site were mostly unstaged. The archeological crew were also digging up the severed heads of statues because in 240 A.D. the city had been seized by the Sassidians and all of its inhabitants, as well as statues, were beheaded. These real – potentially cursed – artifacts are those featured in the film!

That is not all. In his autobiography, The Friedkin Connection, Friedkin recalled that as the archeological crew had not actually unearthed a large statue of Pazuzu as called for in the script, Warner Bros. had created one and had it shipped to Baghdad via the reliable Flying Tigers shipping company. The gigantic statue allegedly spooked so many customs officials that the package disappeared and was finally discovered all the way in Australia.

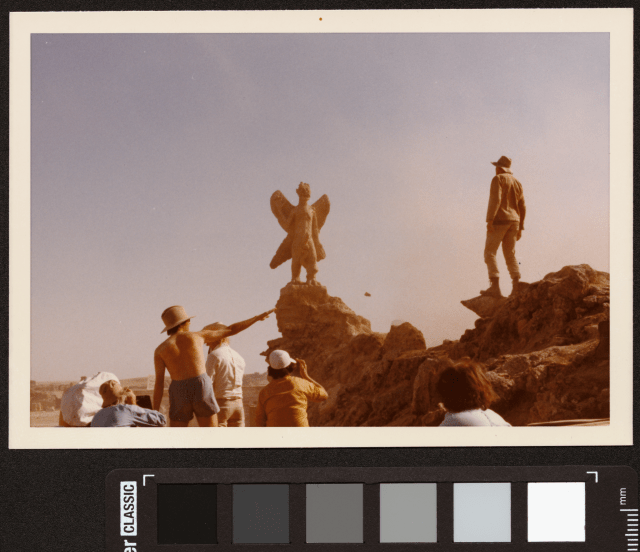

Pictured above: Shooting Father’s first encounter with the Demon Pazuzu in Iraq.

When the statue finally arrived in Iraq, Friedkin attempted to lure vultures to it by hanging scraps of meat on it (it did not work) and staged a scene with dogs fighting over bread at its feet. While he did not attract any vultures to hover over the statue for a creepy shot in the film, Friedkin did attract the attention of the nearby Yazidis who believed that he was actually worshipping Pazuzu.

Considered by some a subset of the Kurds, and by others as a separate indiginous minority, “Yazidi” translates to “the servant of the creator,” and they have been portrayed both in fiction and non-fiction as “devil worshippers.” This label, however, appears to have been placed on the Yazidis by muslims who have misunderstood their beliefs. The Yazidis are still discriminated against and/or persecuted by the Kurds, ISIL/ISIS, the Turkish Armed Forces and the Syrian National Army.

The religion of the Yazidi’s origins can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamian. While the Yazidi believe in one God, there are also “Seven Mysteries” or angels who have been appointed by God to take care of the earth. One of these “Seven Mysteries” is Melek Taus, an angel represented in the form of a peacock who, similarly to Iblis, who is considered to be the Quran’s answer to Satan, refused to bow to Adam. While Iblis was thrown out of heaven for refusing God’s order, the Yazidi religion celebrates Melek Taus’ refusal as a sign that he was truly devoted to God. While a deeper, theocratic study of the issue is much more complex, it is generally believed that the conflation of the stories of Melek Taus and Iblis is responsible for the Yazidi’s label as “devil worshippers.”

When the Yazidi contacted Friedkin’s Ba’athist minders and requested an audience with the American, the Ba’athist officials strongly advised against the visit as they would have to pass “through Kurdish territory to a dangerous place they couldn’t control.” (The 80s and 90s would later see fierce conflict between the Kurds and Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi government which lead to Saddam’s infamous use of chemical weapons against the Kurds)

Friedkin’s direct minder decided to take the risk and, disregarding party instructions, brought Friedkin to meet the Yazidi sheikh who had requested the meeting. As they made the drive to the Yazidi camp situated north of Mosul, Friedkin was warned not to harm the flies which the Yazidi allowed to infest their camp, believing that they contained the spirit of Malak Taus, or his other name “Shaytan” (“Shaytan” is also Arabic for “devil” and undoubtedly another reason for the muslim confusion about the Yazidis).

As Friedkin sat with the Yazidi sheikh, all the while being devoured by swarms of flies, he did his best to explain that the “sacrifices” he had made to Pazuzu were actually for a movie. Though the Sheikh had never seen a movie, or met an American, he explained the Yazidi beliefs to Friedkin, who found him to be modest and curious. Friedkin had certainly managed to get to the very heart of his subject matter! Who is to say that Friedkin did not bring some of the region’s spirits back home with him?

While most of the theories surrounding the “Exorcist Curse” center simply around the film being about demonic possession, they stop short of getting to the real compelling potential explanation. Director Bill Friedkin’s insistence on shooting in the real birthplace of the film’s demon, and his contact with the Yazidi who, while perhaps not proper devil-worshippers, had a knowledge of and a very real belief in The Exorcist’s demon, Pazuzu, are way more believable than anything else put forward by superstitious film buffs.

Lucky for John Boorman, director of the aptly titled Exorcist II: The Heretic, he largely dodged the curse when he abandoned plans to shoot in Ethiopia and instead shot most of the film on the Warner Bros. backlot. He did not escape the curse entirely, however, as the sequel grossly underperformed ($30.7 million box office versus $441.3 million of the original) and was largely panned by critics.