During the Arab Spring of the early 2010s, the popular news consensus was that the Syrian government was on its way out. The rapid collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s government in 2011 was a clear blueprint and the rapid rise of anti-government forces in Syria seemed to show history repeating itself. Cue one of the bloodiest wars in recent memory and despite everything news pundits and national leaders repeated ad nauseam, the Syrian government remains in control. It’s straight-up become a joke that people calling for the government’s removal are more likely to be unseated themselves! So what’s the deal? What is the Syrian government exactly?

Ba’athism

The Ba’ath party was founded in 1947 in Syria and espoused a political theory called Ba’athism, with Ba’ath being Arabic for ‘rebirth’, summed up in its three-word slogan “Unity, freedom, socialism.” The theory, put simply, calls for a united pan-Arab state based on principles of ‘Arab socialism’ (a loosely defined concept), Arab nationalism and anti-imperialism. It advocates secularism and the development of an ‘enlightened’ Arab world to reverse the post-Ottoman collapse trend of the Arab world being subservient to powers in the west. To actually attain these goals, they took a few cues from Leninism, the political philosophy of the Soviet Union and many other Marxist states.

Now, this doesn’t mean they were Marxists or anything. They just recognised that if you want to achieve total social transformation in a short time, you needed complete political control to circumvent reactionary powers like foreign capital, the clergy and sectarian movements. For this reason, the Ba’ath party was to function as a vanguard party, meaning that the most revolutionary elements of society would lead the party towards a collective goal, overruling the immediate interests of the majority for the sake of their benefit. Despite this, Ba’athism didn’t call for the suppression of freedom of speech, they desired a kind of benevolent dictatorship that would hand over power when Arab society was ready.

Among the many differences they had with Marxists, the Ba’athists didn’t see the working class as the inherent revolutionary class, nor did they see communism as an ultimate goal. Concepts like dialectical materialism were similarly alien to ‘Arab socialism’. They saw ‘socialism’ (in this context, pretty much just heavy state interventionism, not even abolishing capitalism) as a means to aid the ‘liberty’ of Arabs by unshackling them from poverty, foreign exploitation and a lack of basic utilities like education and healthcare. The movement’s founder Michel Aflaq argued that this was perfectly in line with Arab nationalist ideals, claiming that the roots of Arab socialism take as much or more from the prophet Muhammad than Marx.

The Coup

So yeah, most of that is totally irrelevant to modern Syria. What, you thought Syria was Ba’athist just because I told you it was? Of course not, they’re neo-Ba’athist. And no, that’s not the same thing. You see, the Ba’ath party may have come into power in Syria in 1963, but that doesn’t mean things just went off without a hitch. A schism existed in the party from the very beginning between those backing Aflaq and a younger, mostly military-led faction. In 1966, this resulted in a coup that drove Aflaq and his followers out of the country, while putting fresh-faced Salah Jadid into power.

This marked Ba’athism’s sudden ‘leftist’ turn, marked by the Syrian government’s co-operation with the Soviet Union, rapid nationalisation policies and heightened hostility towards the likes of Israel. The pan-Arab ideal, the whole bedrock Ba’athism rested upon, took a back-seat and led to a schism with branches of the party based outside of Syria. When the Iraqi Ba’ath party seized control in 1968, there was zero attempt to reunify or create a united Syrian-Iraqi state, rather both started attacking each-other and pro-Aflaq Syrian Ba’athists defected to Iraq.

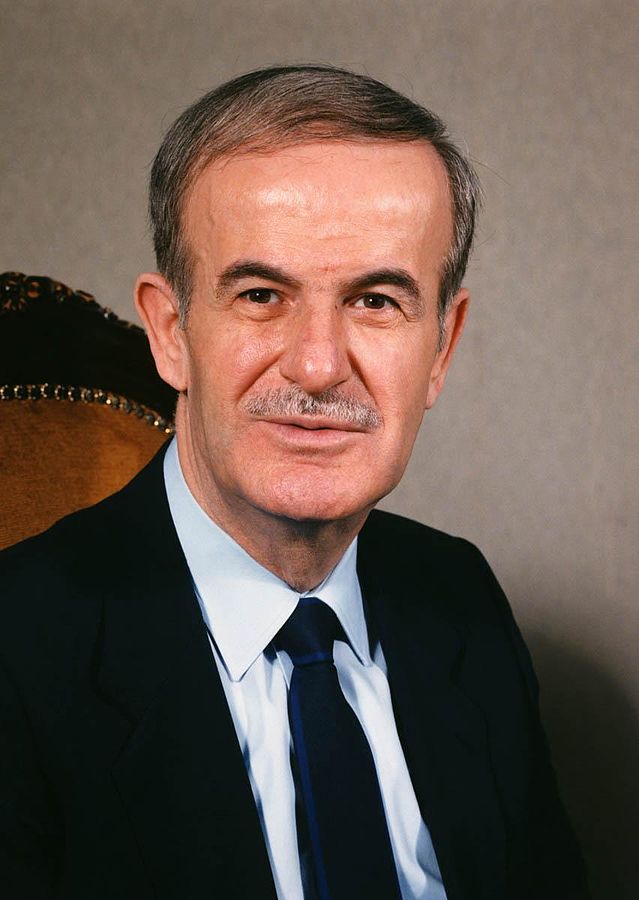

In 1967, the Syrian government took part in the six day war against Israel. Given that Israel is still standing and the war is called the ‘six day war’, you can probably guess how it went for Syria. The Golan Heights, a region of Syria, was seized by Israel afterwards and remains part of their territory to this day. This didn’t exactly make Jadid popular, nor did the faltering economy. Unfortunately for him, he wasn’t very good at remembering how he took power in the first place, because while he controlled the government, the military arm of the Syrian state was firmly under the control of one Hafez al-Assad, the defence minister. By 1969, Jadid had already been marginalized.

The last hurrah of the Jadid administration was to aid the Palestine Liberation Organization in the Jordanian civil war of 1970, something that Assad and co were not supportive of. After mutual antagonisms for several months, Jadid attempted to fire the undisputed leader of the Syrian military, which ended about as well as one would expect. On the 13th of November 1970, the ‘Corrective Movement’ was launched, which functioned as yet another coup as the army arrested Jadid loyalists and eventually the man himself. The coup was bloodless and went off without a hitch, proving popular among the Syrian masses.

Syrian Government under Hafez al-Assad

So now we get to the more modern Syrian government. When Jadid got booted into prison (where he’d languish until death in 1993), the Syrian government under Hafez al-Assad began sweeping reforms. Aflaq supporters were invited back to the party, though their influence was greatly marginalized. Religion was raised in status once more, with Hafez presenting himself as a pious Muslim and much of his cabinet was to be made up of Sunni Muslims. This is despite the fact that Assad himself was Alawite, something that made him very controversial in a region that had been dominated by Sunni’s for several hundred years.

The legacy of Jadid was most prominently undone by Assad’s economic reforms, in which the private sector was greatly expanded and alliances were made with Syrian business leaders. Relations with the Soviet Union cooled as Syria settled back into more of a ‘non-aligned’ status, still maintaining unquestioned political control while liberalising the economy. Pan-Arabism was reframed in several ways, with foreign investments from other Arab countries justified under this pretence.

This tactic actually worked quite well for Assad, as the rising price of oil in 1973 fuelled an economic boom period that further solidified the Syrian government while leaving the legacies of both Aflaq and Jadid in the dust. The latter half of the 70s saw economic contraction once more, though at a level the Syrian government could handle, at least for the time being. Continued trade with the Soviet Union and anti-Israeli Arab nations ensured that whatever hostility the Syrian government saw from the west, it was a storm that could be weathered.

The party remained ‘Arab socialist’ even as the Aflaq-stated goal of commandeering the economy for the liberty of Arabs was sidelined in favour of making allies for the Syrian government out of the local bourgeoisie. The party also centralised its authority, recognising that the previous two coups were only possible because of a split between the civilian and military government. This ended. The military and civilian government became solidified under presidential control, while rival factions were overcome through tactical support of the Syrian middle class, Alawite minority and anti-Islamist Sunnis.

Syrian Government Transforms

A very notable change to the Ba’ath party upon Assad’s ascent was growth. As I mentioned, the purpose of the Ba’ath party was to be a vanguard of the most progressive elements of Arab (specifically Syrian) society, comprising an elite minority. In 1970, Ba’ath party membership stood at around 65,000. In 1981, this number stood at 374,000, only to increase to nearly a million in 1992 and 1.8 million by 2005… Though that’s getting ahead of ourselves. What this indicates is a shift from a rigid vanguard to a more encompassing mass party. This serves two purposes, firstly binding the populace and society more strongly to the party and its ideology, while also diluting the ideological influence of radical leftists.

Even more interesting, the Syrian constitution of 1973 established that while the Ba’ath party is the leading party, other parties can exist that are subservient to the National Progressive Front, a coalition of political parties led by the Ba’ath but allowed limited autonomy. This isn’t too unusual for vanguard movements, after all Korea has a similar front of aligned parties, though it marked a sudden shift away from complete Ba’athist domination. All the same, the constitution mandated the Ba’athists always held 50+1% of seats and that parties in the NPF could not canvass among the students and military for instance.

The 1973 parliamentary election was the first since the Ba’athist took control and resulted, of course, in an overwhelming victory for the Ba’athists, followed only by several aligned socialist parties and a cluster of aligned independents. This allowed the Syrian government to be more representative of its populace, giving voices to minority interests and alternate viewpoints that did not challenge the overall authority. This move was, however, possibly a trigger for some of the earliest signs of organized uprising in Ba’athist Syria.

The most solidified opposition to the Ba’ath party was always conservative Muslims, coalesced behind the Muslim Brotherhood. Increasing unease, particularly due to Assad being an Alawite, led to a spate of sectarian murders in 1976 with links to the Muslim Brotherhood which gradually ramped up in intensity until a massacre of cadets at the Aleppo Artillery School in 1979. Mass Islamist strikes and demonstrations, coupled with assassinations and occasional massacres was responded to in kind, with tit-for-tat killings occurring until the siege of Hama in 1982, in which the Syrian government crushed the revolt with thousands dead.

Consequences from this near civil war were great. Pro-government rallies began focusing more heavily on Assad himself than the Ba’ath party, perhaps a reflection of how the Ba’ath’s leading ideology had taken a back-seat to national unity. A cult of personality began to form around him and his family, coupled with the rising prestige of the military and Syrian secret services. While the Syrian government under the Ba’athists had flexed their authority since its inception, it was at this time that its modern incarnation truly took shape.

Syrian Government Now

On the 10th of June, 2000, Hafez al-Assad died of a heart attack after thirty years in charge. The following month, his son Bashar al-Assad was elected unopposed as the new president, another sign of how much more important the Assad name had come than Ba’athism itself. While Bashar was initially believed to be a more ‘moderate’ leader who might allow major reforms to the Syrian government, these thoughts faded after a crackdown in August of 2001. Once again, the opposition movement was driven back underground and the Ba’ath party remained absolute.

Bashar al-Assad oversaw increasing economic liberalisation and upon the uprisings that spread into a catastrophic civil war, several more major changes were made. The constitution was updated once more, notably casting aside the Ba’ath party’s guaranteed political majority and allowing for legal opposition parties, though the war and continued state interference has made it impossible to test the implications of such a reform. Attempted elections have been frequently condemned as fraudulent, while much of Syria’s territory and populace remained out of Syrian government control throughout the election process.

To deal with the chaos of the war and mass international sanctions, Syria has aligned itself closer with regional allies, most prominently with Iran and Russia, both of which have given the Syrian government a backbone of military, political and economic support through the troubled decade. Many have suggested this amounts to a loss of Syrian autonomy, particularly Sunni Muslims feeling increasingly threatened by both Alawite political dominance and the political influence of Iran’s Shia government. For this reason, among many others, much of the government opposition has consolidated itself in Idlib province, where a broadly Sunni led opposition government survives with Turkish support.

Such is the state of the modern Syrian government. Changes have been made to the political system under Bashar al-Assad and many more changes are presumably on the table for the future, though whether they function in reality and how well they function will depend on the war ending. Even the Ba’ath party itself hasn’t escaped the war unscathed, with membership collapsing and party organs taking a back-seat to the authority of the military. For the time being, the Ba’ath party and Bashar al-Assad don’t seem to be going anywhere.

Want to see Syria for yourself? Check out our group and independent tour packages