Assuming you’ve never lived (A) in any socialist countries or (B) during the Zimbabwean hyperinflation crisis, then money is a very simple thing. You to work, you get paid at the end of the month, and you blow it all in two weeks. You then live off beans and toast for the last two weeks of the month, and rinse and repeat.

Socialist countries don’t exactly work like this. Well; China, Vietnam and Laos actually do, but for the purposes of this article we’ll deal with actual socialist countries like North Korea and Cuba.

In truly socialist countries (the former Eastern Bloc and old-school Maoist China included), you have what is known as ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ currency. What’s the difference? I’m glad you asked, hypothetical reader. Read on…

Table of Contents

- Socialist countries and soft’ currency

- Hard currency

- Socialist countries: Cuba and the dual-currency system

- The necessity of hard currency

- How to make a socialist bourgeoisie

Socialist countries and soft’ currency

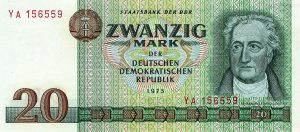

A ‘soft’ currency is the official currency of socialist countries: North Korean won, Soviet rubles and East German Marks are all some examples of such a currency. Unlike currencies in most countries, which are free-floating and have fluctuating values depending on the international market, soft currencies are pegged at a fixed rate. This fixed rate usually has no basis in economic reality.

Hard currency

‘Hard’ currency is a free-floating currency (usually an internationally recognised one from a prosperous country) that is used as the de facto currency in socialist countries, whether overtly or otherwise. Examples of this include the long-time use of the USD in Cuba and the use of euros, USD and Chinese RMB in North Korea.

Wait, what?

It’s not immediately intuitive why it should be done this way, so let’s give an example of socialism in practice as it pertains to currency.

In North Korea, the won has an official exchange rate of 140 won to a euro, set by the state. In reality (as reflected by black market prices), this rate is closer to 7000-8000 won per euro.

Let’s say you go to Kwangbok Department Store in Pyongyang. You see a sweet TV on sale for 1400 won. At the official exchange rate, this is 100 euro. But if you were to go to the black market, you could pick that up for around 2 euro. Awesome deal, right? Well, not exactly. It’s not as if the DPRK powers that be are not aware of this workaround. In order to buy that TV, you need to first bring actual euros (the semi-official hard currency of North Korea) to the store, have it exchanged at the official rate, and present your receipt proving you did this when you buy the TV. In this way, you’re basically paying 100 euro for the TV no matter how much you try to game the system.

Socialist countries: Cuba and the dual-currency system

Moving onto Cuba, one of the most well-known socialist countries. Cuba has two currencies – the soft currency is the CUP, or ‘moneda nacional’. The hard currency is the Cuban convertible peso (AKA ‘CUC’, pronounced roughly as ‘kook’). According to official exchange rates, 1 CUP is equal to 1 CUC. In reality – again, reflected by black market rates – it’s around 25 CUP to 1 CUC.

How does Cuba have a currency that is both ‘hard’ and Cuban, rather than foreign? We’re glad you asked!

Cuba historically used the USD as its hard currency of choice. However, due to the trade embargo imposed upon Cuba, they couldn’t exchange USD directly with the US, meaning that they lost around 10% per transaction. To counter this they employed some economic wizardry and invented the CUC, valued at exactly 1 USD. All well and good, but how did this stop them losing 10%? By making foreigners foot the 10% bill, of course. When exchanging USD for CUC, foreigners pay a 10% service fee, effectively shifting the loss to the person exchanging. When exchanging euros or Canadian dollars, however, there is no surcharge. This, ironically, means that the most expensive way to buy CUC is with the currency it’s pegged against.

So what, exactly, is the point of the moneda nacional (CUP)? It’s often said that Cubans earn as little as $30-$70 (USD) per month, and are therefore in poverty. Now whilst this is technically true, it’s a little disingenuous and very simplistic. Whilst true that the average salary is 1000-2000 CUP (40-80 USD) per month, this does not take into account the subsidies provided by a fully socialist state. A bus ride costs CUP 0.5 (0.02 USD) and a fruit juice CUP 2 (0.08 USD), to give it some context.

The necessity of hard currency

If the state provides so many subsidies, why does the CUC even exist? For that we need a history lesson. Socialist countries have always needed hard currency for imports (oil, minerals, food that cannot be grown locally etc. etc.). Even in Soviet days, foreigners were required to pay for services either with a foreign ‘hard’ currency or else soft currency exchanged at the official rate. An interesting example here: in the 1980s, North Korea had four kinds of differently-coloured won: one for locals, one for third-world countries, one for Soviet countries and one for filthy capitalist dogs. Put simply: if US shipping magnate Richie Randolph Rich was having a beer with his mates Boris and Kim in 1980s Pyongyang, Richie’s beer would be twice as expensive as Boris’ and four times as expensive as Kim’s. Take that, imperialist dogs!

Another important reason for hard currencies is that whilst many things are subsidised or outright provided by the socialist state, Coca Cola Company and Levi’s don’t take commie funny money, in the same way that McDonald’s doesn’t accept cartons of Marlboros as payment just because you’re an ex-con. This means that citizens of socialist countries needed access to foreign currency when travelling abroad – which means that socialist countries need a method of obtaining foreign currency. Pyongyang department stores (and, until the mid-nineties, Beijing ‘Friendship’ stores) were one of the methods this was done.

Coming back to the CUC, and why it’s even necessary: to start with, the CUC is no longer the sole domain of foreigners and diplomats. It can be legally held and earned by Cubans (unlike the USD). The CUC has become kind of a status symbol and represents not only access to high-end consumer goods, but also access to the burgeoning ‘middle class’ (inverted commas because, as a socialist paradise, Cuba is of course classless).

How to make a socialist bourgeoisie

The original boom in Cuban tourism brought with it a commensurate rise in jineterismo – crime that revolved around scamming tourists. The reason for this was pretty simple: by swindling tourists, you could make in a day what would usually take a month. This was addressed in 2011 by Raul Castro, who instituted a number of reforms. Whilst initially small, these reforms legalised hundreds of self-employed professions – bars, stylists, restaurants, shops and a myriad of other service professions were legitimised. And why thieve off Johnny Foreigner and risk jail time when you can just get him to pay you?

Naturally, of course, when you legalise entrepreneurialism, you get entrepreneurs. This leads to the haves and have-nots: those with foreign currency to spend, and those without.

It’s very interesting to see the changes in Cuba brought about as a result of this embrace of the entrepreneurial spirit, and seeing the opening of what was once a closed economy makes for an exciting time. It’s also pretty sad to see what it say about human nature and the nature of materialism: no matter how much is provided by the state or nature (Cuba is self-sufficient when it comes to food), people are always gonna want the next iPhone (this paragraph was typed on my iPhone X®).

Leaving aside the politics of socialist versus capitalist currencies: yes, you can easily survive on USD or CUC when in Cuba. But if you want a real taste of full-on socialismo, grab some CUP, head down a back alley and have some peso pizza washed down with dodgy draft beer from a rusty tap. It’s what Marx would have wanted.