When the Bolsheviks enacted the October revolution of 1917, the promise was of a new society with no precedent in history. A society distinct from what came before, where the barriers of class would be dissolved, where divisions of all kinds would be subsumed into the collective socialist project. In the new Soviet society, humanity itself would be transformed, as epitomized by the new Soviet man! …At least, that’s the idea behind it. Curious yet?

What’s a New Soviet Man?

As quoted in the 1976 edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia with regard to the Soviet people:

…the historical, social and international community of people with a single territory, economy, socialist culture in content, a union state of the whole people and a common goal – the building of communism; arose … as a result of socialist transformations and the convergence of the working classes and strata, of all nations and nationalities.

S. T. Kaltakhchyan, ‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia‘

This is the ideal the Soviet Union wanted for its people. United by their territory, people of all Soviet nationalities working towards the common goal of communism, directly as a result of the socialist transformation! It functioned both as a new form of national identity and a new culture, with values and ethos entirely separate to non-socialist nations.

Why a New Soviet Man?

The concept itself isn’t terribly revolutionary. Anyone can point out that society is influenced by its surroundings, which is why unique cultures, mannerisms and concepts emerge in different countries. Typically, however, this is a natural product of how the environment develops, while the fledgling Soviet nation attempted to predict the end result and work consciously towards achieving that! They recognized that the society inherited from the Tsarist empire was one dominated by religion, disparate national/ethnic identity, divided by class and wholly unsuited to the socialist society that was to come.

We can look at a 1920 article by Vladimir Lenin, in which a clear statement of intent for the new Soviet man was laid out:

…we can, and should, get right down to the problem of communist labour, or rather, it would be more correct to say, not communist, but socialist labour; for we are dealing not with the higher, but the lower, the primary stage of development of the new social system that is growing out of capitalism.

Communist labour in the narrower and stricter sense of the term is labour performed gratis for the benefit of society, labour performed not as a definite duty, not for the purpose of obtaining a right to certain products, not according to previously established and legally fixed quotas, but voluntary labour, irrespective of quotas; it is labour performed without expectation of reward, without reward as a condition, labour performed because it has become a habit to work for the common good, and because of a conscious realisation (that has become a habit) of the necessity of working for the common good—labour as the requirement of a healthy organism.

It must be clear to everybody that we, i.e., our society, our social system, are still a very long way from the application of this form of labour on a broad, really mass scale.

…To achieve big things we must start with little things.

Vladimir Lenin, ‘From the Destruction of the Old Social System to the Creation of the New‘

The kind of labourer envisaged by the end of socialist construction is one who habitually works for the collective good of the people, who has been shaped by new social system to no longer see work as something coercive, where their wellbeing is conditional on doing the work. Now, is this realistic? It’s hard to say. As Lenin says himself, they were a very long way off that being possible, as the nature of the state needed to change to be viable for the people. This is in keeping with Marx’s own theories on the ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’, in how the relations of people to the means of production shapes and maintains the surrounding culture.

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.

Karl Marx, ‘A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy‘

Early Efforts to Create the New Soviet Man

One of the earliest efforts to redefine the character of the new Soviet man was the state crackdown on religion. On January 23rd 1918, only a few months after the revolution, the ‘Decree on Separation of Church and State’ was signed into practice, officially severing the power and authority of the church and other religious institutions. Key to establishing the new superstructure is to destroy the old. The Russian clergy were closely entwined with the Tsar and maintenance of the monarchy, as well as latching onto other ideals that conflicted with the new goals of the state. While the religious themselves were not stamped out (with some status returned after WW2), their authority over the masses was broken.

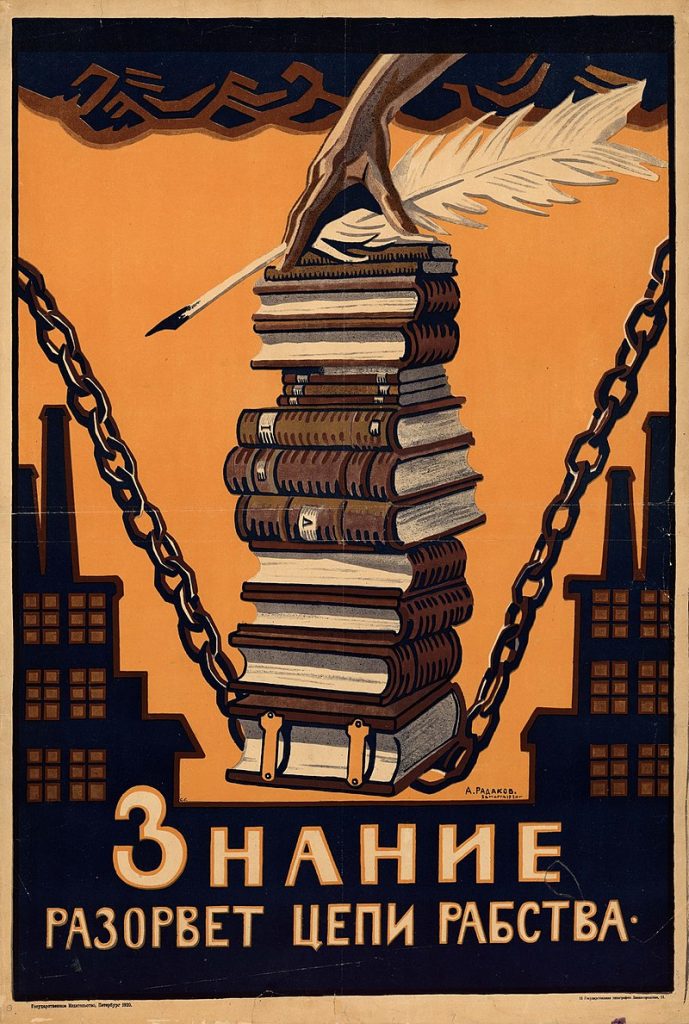

Perhaps the most obvious immediate effort to develop a new Soviet man was the mass literacy campaigns (Likbez) conducted almost immediately after the revolution. The Tsarist state that came before had little interest in developing the education of the masses, leaving much of the populace dependent on the church for guidance. By simultaneously attacking the old institutions of learning while advocating a new one, the popularity of the revolution was able to grow. Every settlement of over 15 illiterate people was to get its own literacy school with 3-4 month courses, with adult workers granted a two-hour shorter working day without a loss in pay to assure their attendance. Alongside education in literacy, there was also education in Leninism.

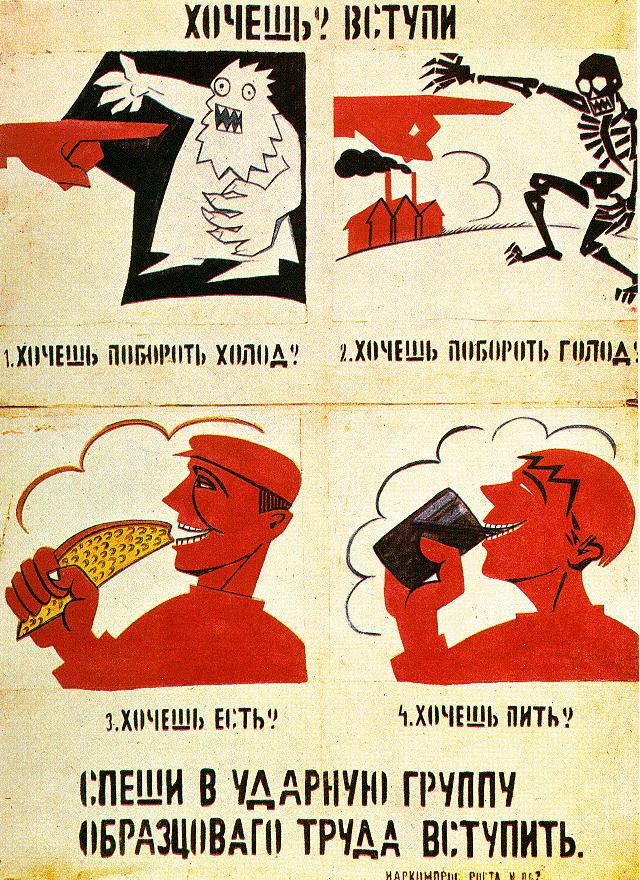

Another goal was to develop an entirely new proletarian culture. As the superstructure of the state is most strongly reflective of the ruling classes, there had never been a state with an authentic proletarian superstructure. To address this, the ‘Proletkult‘ movement formed in the early days of the revolution. This association of largely independent artists and creatives experimented with new ways to explore working class culture. By 1920, the Proletkult claimed 84,000 members with over 500,000 casual followers, producing art, music, film, literature and propaganda designed for the masses. The work of the Proletkult remains influential to this day, however, its influence in the USSR waned in the early 20s as the party reasserted control, largely replaced with ‘socialist realism’.

New Soviet Woman

For there to be a new Soviet man, there must naturally be a new Soviet woman as well. In the early days of the revolution, the pursuit of women’s rights was pursued with the same fervour as workers rights. The ‘Zhenotdel’ formed in 1919 at the behest of Bolshevik feminists Alexandra Kollontai and Inessa Armand as a movement specifically to address the ideological education and development of women in the new Soviet era. Coming out of the deeply patriarchal culture of the Russian empire, it nonetheless saw major early successes with the formation of ‘women delegate assemblies’, which organised and educated women workers and reached over 620,000 members by 1927.

These organizations made great strides towards womens rights in the new USSR. Campaigns were launched in the far-east to uplift womens rights in Islamic regions, encouraging women to lift their veils and struggle against the immense patriarchy they faced, often putting their lives on the line for that social progress. In 1920, abortion was legalized for the first time and divorce became much more available to women. The broad push towards communal living helped ease the burden on mothers and housewives and indeed, the Soviet Union became the first country to recognize International Womens Day as a public holiday.

The psychology of the new, independent, single woman, according to type, is reflected in the image of the rest of her contemporaries: the traits of women, who belong to the army of those earning their own livelihood, formed by life itself, by degrees also begin to be the hallmark of the others. It matters not that those who earn their own livelihood are still in the minority, that for each one of them two, even three, women of the old type emerge. Working women set the tone of life, and form the character in respect to the image of the of our time.

With her transvaluation of the moral and sexual standards, the new women shake the unshakeable pillars of the souls of all the women who have not yet embarked upon the new thorny path. The dogmas that keep a prisoner of her own world-view lose their power over their minds….

The influence of women earning their own livelihood spreads far beyond their own circle. With their criticism, they “poison” the minds of their contemporaries, they smash old idols, they raise the banner of revolt against those “truths” with which women have lived for generations. By liberating themselves, the new, single women, earning their own livelihood, also liberate the passive-backward spirit, as this has been molded down the centuries, of their contemporary sisters.

Alexandra Kollontai, ‘New Woman‘, 1918

Alas, as the 20s drifted towards the 30s, these gains would not last. In 1930, the Zhenotdel was disbanded and the largely male-dominated party affirmed that the question of gender equality had been settled. As the concept of the new Soviet man focused increasingly on the ‘man’ side of things, women were once again relegated to the roles of mothers, educators and houseworkers. Their status had improved from the Tsarist era, but rights won in the early years of the revolution were gradually stripped away, with even abortion being banned once more in 1936. The abandonment of womens rights may serve as an omen for the concept of the new Soviet man as it evolved – or devolved – through the years.

Stakhanovites

If there was a shining example of the new Soviet man as one individual, that would be Alexey Stakhanov. A coal miner who in 1935, reportedly mined 102 tons of coal in six hours, a whole fourteen times his quota. The Soviet press praised his efforts as a shining example of the new Soviet man, hardworking in the construction of socialism during the height of the second five year plan for industrialization. The ‘Stakhanovite movement’ built itself around his example, encouraging hard work to exceed production quotas and serve as a living example of the new Soviet man, someone to emulate and speed up the fruits of socialist construction.

The concept of the Stakhanovite later spread outside of the USSR, notably being maintained today by the Korean Chollima movement. Within the USSR itself, the Stakhanovite system faced pushback after the death of Stalin. While it had many notable successes, often being associated with rising wages, it also put undue pressure on many workers and correlated with indefinitely rising production quotas, sapping away at the benefit they gave to workers. Even after its repudiation, the fundamental concept remained a regular feature of Soviet workplaces. ‘Socialist emulation’, as it was referred to, continued to encourage ‘friendly competition’ among workers to help achieve the greater goal.

Komsomol

The new Soviet man had to start out as a new Soviet boy, so it was that the Komsomol worked to develop this new kind of human from a young age. The Komsomol (All-Union Leninist Young Communist League) formed in late 1918 as a political youth movement to spread socialism among the young people of the Soviet Union. During a speech in 1920, Lenin summed up the task of the movement in one word: Learn. To learn both in theory and practice how to conduct themselves as communists and aspire to be an example of the new Soviet man.

It is the task of the Young Communist League to organise assistance everywhere, in village or city block, in such matters as — and I shall take a small example — public hygiene or the distribution of food. How was this done in the old, capitalist society? Everybody worked only for himself and nobody cared a straw for the aged and the sick, or whether housework was the concern only of the women, who, in consequence, were in a condition of oppression and servitude.

Whose business is it to combat this? It is the business of the Youth Leagues, which must say: we shall change all this; we shall organise detachments of young people who will help to assure public hygiene or distribute food, who will conduct systematic house-to-house inspections, and work in an organised way for the benefit of the whole of society, distributing their forces properly and demonstrating that labour must be organised.

Vladimir Lenin, ‘The Tasks of the Youth Leagues‘

The Komsomol grew rapidly in the 20s and 30s, reaching 4.3 million by 1938, only to explode during the second world war and reach over 10 million. Members were allowed between the ages of 14 and 28 (with separate sections and responsibilities for certain age brackets) and they typically involved themselves directly in all aspects of life, from ideological development to physical development through sport, from helping out on farms and factories to organizing local events in their hometowns. The younger members of the Komsomol were notably part of a group known as the ‘young pioneers’, which may seem a little familiar if you’re reading this site… In many ways, these were the socialist equivalent to the boy scouts.

The Moral Code of the Builders of Communism

Upon the death of Stalin 1953, many aspects of Soviet society began to change, at first subtly but then more strongly as the USSR reformed itself into its early 90s collapse. We can see an early example of these changes explicitly through the continued attempt to develop the new Soviet man. In 1961, the ‘Moral Code of the Builder of Communism’ was adopted by the 22nd Congress of the CPSU. At first glance, it seems to follow the earlier trends well, preaching devotion to communism, working class solidarity, a Soviet identity above regional identities, etc. Though one might notice it focuses almost entirely on civic duty while lacking revolutionary ‘teeth’. No-doubt a product of Khrushchev’s ‘peaceful coexistence’ policy.

Reportedly, the moral code was explicitly written with teachings from the Bible in mind, something that Putin has publicly praised himself. If one were to look back to Lenin’s speech to the Komsomol, he states in unambiguous terms:

We reject any morality based on extra-human and extra-class concepts. We say that this is deception, dupery, stultification of the workers and peasants in the interests of the landowners and capitalists. We say that our morality is entirely subordinated to the interests of the proletariat’s class struggle. Our morality stems from the interests of the class struggle of the proletariat.

Vladimir Lenin, ‘The Tasks of the Youth Leagues‘

You may wonder why this is a big deal, but you need to consider the premise of this whole article. This is about the New Soviet Man! For something new to be stepping backwards into the morality of an old society, the fundamental purpose of the new society must be being undermined. Indeed, the Soviet Union was on a track towards denying the necessity of a new Soviet man and instead simply achieving the standards of a capitalist society through more ‘collectivist’ means. It’s no surprise then that in 1986, the moral code was revised once more, stripping the meaning of communist morality to three points. Collectivist morality, humanist morality and active morality. Proletarian morality is conspicuous in its absence.

Later Years

During the 60s and 70s, while party focus on the ‘new Soviet man’ may have greatly diminished, the infrastructure for such an undertaking only seemed to grow. The post-war industrialisation allowed earlier plans to be expanded upon exponentially, most notably in the case of mass cultural centres. Just as capitalist society is typically overflowing with facilities to engage both passively and actively with capitalist culture, so too did Soviet society provide for its people.

According to a source for 1971, the USSR contained 133 thousand clubs, 128.6 thousand public libraries, 553 theatres, 1173 museums and 157.1 thousand cinema installations. Further, in 1970 there were reportedly 5273 thousand public lectures, 2334 thousand amateur performances and concerts, 440 thousand interest circles and 16 thousand universities. Cultural life was vibrant and everywhere using facilities that the old Soviet Union desperately wanted, but no longer having the ideological imperative to use them for the creation of the new Soviet man.

As relations warmed with the west, it became increasingly common for Soviet culture to be subsumed by a desire for western culture. While politics was still being preached, revolution was less than a distant memory for many young Soviet citizens. For those born after the second world war, there was no great struggle with the western powers beyond geopolitical conflict. The question of socialism’s benefit wasn’t the creation of a new Soviet man, it was whether or not socialism could do capitalism better than capitalist countries. As reforms deepened in the 1980s, it became increasingly obvious that it could not.

The Collapse of the New Soviet Man

By the 1980s, the ‘new Soviet man’ was becoming a mockery of a concept, soon to be replaced with the disparaging term ‘Homo Sovieticus’. It acknowledged that the goals set out in the early days of the revolution were not being met, to put it mildly. Soviet citizens were increasingly politically indifferent, feeling trapped by the entrenched bureaucracy of the then-Soviet leadership. They were indifferent to the quality of their work, lazy, chauvinistic, drunk, all kinds of nasty things that had indeed become common in the Soviet Union by the 1980s. The seeds for this downfall had been sown many years before.

As the Soviet government proved themselves the biggest Homo Sovieticus’s of them all, the mid-80s Glasnost and Perestroika reforms of Gorbachev would permanently tear apart whatever vestiges of the new Soviet man were left. Soon, the Soviet identity itself had become an object of derision and secessionist movements grew in strength throughout the Soviet republics. Soon, there were no Soviets. There were no Soviets, but there were plenty of Ukrainians, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians and of course, Russians.

The Soviet Union collapsed, inevitably, as a result of the party quite simply no longer containing Soviets. If the new Soviet man is as described above, then those who accelerated the country faster and faster still towards market reform couldn’t seriously be compared. Of course, one can argue that it was a pipe dream to begin with. That’s been the typical opinion of western scholars who view the whole effort of creating a new Soviet man as laughable at best, horrifying and totalitarian at worst. There certainly were horrors involved in the process and there’s no arguing that it ultimately failed. Though looking back on it now, it’s hard to deny some of those early gains.

Despite the ultimate failure and collapse of both the new Soviet man and the Soviet union itself, polling has regularly demonstrated serious nostalgia for the USSR in many of the former republics. All of them? Of course not. Even the most optimistic Soviet style socialist has to acknowledge fundamental failures that stained its memory in the eyes of whole regions and groups of people. But what exists is a long and fascinating history of an attempt to predict and create the future of humanity. Even if the new Soviet man is a dead and gone concept, it may not be a bad idea to look back through some of the ideas and see what we can carry forward.