Colonialism in Africa was and is, across the board, ruthless and deplorable. Native peoples were made second class citizens on their own soil, their resources were ripped from the very Earth and any hope for competitive economic development with the rapidly growing rest of the world was strangled in infancy. This is all said to preface the fact that many of the initial anti-colonialist movements in Africa were kind of, sort of, maybe a little awful themselves. Ultimately I would say that the ending of foreign domination was still worth the price, but many nations underwent great hardships and it’s worth doing a little retrospective on those. For the example here today, let’s have a look at the Mauritanian dictatorship.

Colonial Mauritania

First of all, we should look at what Mauritania was like before the dictatorship. It was… Well, functionally just a dictatorship but from some asshole sitting in Paris instead of Nouakchott. After the land that would become Mauritania was seized from a series of local independent territories and emirates, the French officially drew the borders on the region in 1912. (Technically they drew it up in 1904, but it took until 1912 to actually seize it all.) By 1920, it had been incorporated into a greater federation of French West Africa, rapidly becoming a full-blown colony.

The native people of the region were the Berbers, a large population of typically light-skinned African peoples who predominantly inhabited the Maghreb (northwest Africa). Due to their lighter skin and predominant practice of Islam, it was pretty common practice in the colonial days for European imperialists to just lump them in with Arabs, despite many differences. Even among the Berbers themselves, it was hardly a single solidified ‘nation’ and inter-tribal conflicts at the time played a large part in France’s ability to conquer the region. What further didn’t help was a kind of ‘caste’ system that existed among many of the natives, where lighter skinned Berbers were regarded as ‘superior’ to darker skinned ‘Moors’ (a broad largely colonial term that encompassed a wide range of people in the Middle East and North Africa). This will be important later.

The Political Establishment

Under French rule, the native people were subjects rather than citizens, thus having no right to democracy and representation. To a limited extent, traditional tribal chiefs still maintained authority, but only to function as French administrators in light of a general lack of interest in investing too many resources and capable figures in administering the region. Much of the land of Mauritania was, at the time, considered economically insignificant and mostly only held for strategic purposes, explaining this relatively hands-off policy towards the colony. Indeed, within French West Africa, Mauritania possibly maintained the most of its original social structures, albeit with a French colonial ‘enhancement’.

As WW2 rolled around and French administration switched towards the fascist Vichy government, things became more tense in the region. People weren’t exactly pleased about the extensive use of forced labor, the rapid escalation of systematic racism and the conscription of locals into the army for a war most had no real stake in to begin with. Tacitly acknowledging that an indifferent racist rulership was perhaps better than an actively hostile one, many flooded to join the Free French movement, for which they would be ‘rewarded’ at the 1944 Brazzaville Conference which afforded many more rights to those in the French African colonies. Many rights, but not independence. Even many of the rights granted were pretty shaky, with the right to vote being slowly expanded from a mere 10,000 active voters in 1946 to full universal suffrage by 1956.

Road to Mauritanian Independence

In November of 1946, Mauritania had the right to vote in one member of the French National Assembly. The French and traditional tribal rulers favored a conservative, pro-French candidate who was instead roundly defeated by Horma Ould Babana, a member of the French Section of the Workers International and thus, a socialist. This scared the ever-loving shit out of the mainstream establishment, fearing the oncoming cold war. In Mauritania, Babana was quite popular. He was committed to independence, oversaw an abolition of forced labor and pursued the French for human rights abuses, at least as far as his position allowed him. When it became possible to form Mauritanian political parties, he formed what became known as the Mauritanian Entente.

In response, the Mauritanian Progressive Union was formed, a more conservative party which supported French interests. In 1951, the MPU’s candidate narrowly defeated Babana in the next election. During the subsequent territorial assembly election in 1952, the MPU won a crushing 22 of 24 seats. It became increasingly difficult for any political opposition to rise to any level of significance in Mauritania. Not long after, Babana fled the country into exile in Morocco, where he began supporting Moroccan claims to Mauritania’s territory. This political stance served to further bury his former party and push support towards the MPU.

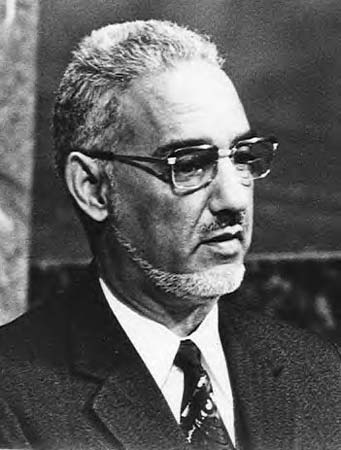

1956 saw the next wave of sweeping reforms which most notably culminated in a degree of local autonomy. Domestic policy could be decided internally, but the French still controlled many key aspects of governance like foreign affairs, defense and much-needed economic aid. A council of ministers was established, and the head of that council was de-facto the prime minister. In Mauritania, the first head of that council was none other than Moktar Ould Daddah, Mauritania’s only lawyer and then head of the MPU, who I can assure you, is very much important to this story.

Independence

In May of 1958, a major political crisis in France saw the birth of the Fifth French Republic and a fundamental shake-up in France’s policy towards colonialism. In September of that year, Mauritania adopted the new French constitution which allowed it to be an ‘autonomous republic’ within the French sphere, a much higher degree of independence. But with this first step taken, a wave of nationalism swept the country and Africa in general which saw the Islamic Republic of Mauritania declared in October, still nominally under French rule but rapidly asserting independence. Work began to draft a constitution and find a way to unite the country under one banner. But… That was quite a hard thing indeed.

Due to the historical construction of Mauritania, strict ‘nationhood’ was a little complex. As said earlier, many of the native people in the region were bitterly divided, with Mauritania roughly splitting into three ‘even’ groups. Lighter skinned ‘Moors’ inhabited the north of the country and were largely nomadic, functioning as the ‘ruling class’ in place of direct French presence. Darker skinned ‘Moors’ meanwhile inhabited the same region and had a common history and culture but were still regarded as second-class citizens and very often made up a slave class in Mauritanian society. Indeed, Mauritania had one of the strongest cultures of slavery left in the world by the 20th century, no-doubt aided by the French colonial support for reactionary tribal structures that otherwise may have naturally crumbled. Finally, there were the black, non- ‘Moor’ populations who were less often nomadic and often lived peasant lifestyles in the south of the country, working agriculture. Among all these competing factions, numerous competing parties existed, and political instability was rampant.

In the same month of the upheaval in France, May of 1958, Moktar Ould Daddah founded the Mauritanian Regroupment Party. This party formed as a merger of the MPU, the formerly opposed Mauritanian Entente and the black nationalist Gorgol Democratic Bloc. Together, these three parties encompassed the main three communities in Mauritania and went on to contest the May 1959 parliamentary elections as the sole participating party, gaining all 40 available seats. This isn’t to say they were the only party around though. Just two months after the founding of the MRP, a mass expulsion of more ‘radical’ figures and youth leaders led to the founding of the Mauritanian National Renaissance Party (Nahda), who favored closer relations with Morocco and tended towards Arab nationalism which alienated the more decidedly African population. Just before the 1959 election, due to the MRP’s already existing political dominance, the declaration was made by Daddah to ban all opposition parties. This was the first real sign of things to come.

Mauritanian Dictatorship

On November 28th, 1960, Mauritania officially declared its independence. France had been gaining little from control of Mauritania and because of Daddah’s rather pro-French attitudes, this was seen as an acceptable result for the former colonial masters. Indeed, Daddah seemed like a great result all around. Even in light of his banning of an opposition party, almost immediately after independence he began calls to rally all the people under one banner, extending his invitation to the previously banned Nahda. In August of 1961, coming up to independent Mauritania’s first election, Nahda actually campaigned for Daddah alongside a number of other parties which saw his inevitable victory. While the new government was largely dominated by the MRP, many of these formerly rival smaller parties had prominent positions.

Given these close ties, Daddah then took it a step further. In November of 1961, a large number of parties including the MRP, Nahda and a group called the Socialist Union of Mauritanian Muslims merged together to form the Mauritanian People’s Party, effectively centralizing all political power and control into Daddah’s hands. The following month, all opposition parties were banned, and increased power was placed in the hands of the presidency, cementing the new Mauritanian dictatorship. Centralized power remained weak for some time after and the one-party nature of the nation was only strictly established in 1964, alongside a brand-new constitution.

While Daddah could be commended for his success in uniting the nation, he was ultimately partisan in the regional conflicts within. As a light-skinned Berber, he favored their interests and paid little attention to the constant slavery that dark skinned Berbers faced, as well as the separate concepts of nationhood and identity held by the southern black African population. In 1966, the study of a particular Berber form of Arabic was made compulsory, stoking fears of Arab domination among the black African community. That same year, discussion of the endemic racism in the country was itself cracked down on. Towards the end of the 60s, major strikes began, and the dictatorship was put to the test, beginning a wide array of crackdowns on those who protested.

Push for Further Independence

By this point, Mauritania was nominally an independent state. But only politically. Economically, it was a whole other story. While political ties to France were lessened and Mauritania began to involve itself in the Non-Aligned Movement, the country was still very much tied to its former colonial master. At least initially, the country continued using the Franc as its currency and much of its economy was built upon French economic aid, heavy exports to France and the loaning of its natural resources to foreign companies. Most notable were massive iron ore deposits that in 1963 were being operated by a foreign company. As the 60s wore on, these economically invaluable miners went on strike for two months and perhaps in desperation, Daddah sent in the army who killed several of them. In an attempt to both control and placate the trade unions, large factions of the unions were incorporated into the government in 1972, while the remaining faction was functionally outlawed.

When Morocco formally gave up territorial claim to Mauritania in 1969, a great deal of breathing room was afforded to the regime to take stock and alter course. No longer needing French support, the government announced plans to ‘review’ agreements set up between Mauritania and France. Planned economic and defensive agreements were scrapped and in 1973, Mauritania left the Franc behind and started a new currency. The following year, the mines that had been until then largely controlled by France and which made up close to 80% of exports was nationalized, signaling a subtle shift towards ‘socialist’ politics which was used to court some new allies in the east, most notably China who began to shoulder the burden of a much-slackened trade supply with France.

In 1975, a new charter from Daddah called for an ‘Islamic, national, centralist and socialist democracy’ for Mauritania. All so vague that they could be rather twisted to placate all sections of the population. Hardly the first time Daddah had done so, but once more, the opposition was temporarily quietened. In light of a series of droughts that had ravaged the country during the early 70s, this renewed support was much welcomed and urged Daddah onwards to further unify the nation and build a better future… Which is where the real fuckups began.

The Regime Crumbles

We’ve talked before here about the Western Sahara independence movement, particularly noting that it was first truly put to the test during a joint Moroccan-Mauritanian invasion of the territory in 1976, as part of mutual ambition to conquer and colonize it. Mauritania had far less public support than Morocco for such an incursion, plus a much weaker military to actually carry it out. The Polisario Front, the main freedom-fighters based in Western Sahara were quick to pick up on this and start fighting back with firepower the Mauritanian’s simply couldn’t handle.

Not only could Mauritania not hold the territory it tried to take, the Polisario Front began attacking Mauritania directly, in particular the iron mines that were the beating heart of the fragile economy. Conscripted African soldiers had no idea why they were being forced to participate in what was seen as an ‘Arab’ conflict in which they had no stake, and which could very well have resulted in their further marginalization in Mauritanian public life. Unrest continued to rise and Daddah could only respond by cracking down harder, issuing a ‘defense tax’ to help fund the military while diverting other funds away from much-needed projects throughout the country. The stability Daddah had formed was crashing down around him.

In July of 1977, the Polisario Front launched missiles directly into the capital of Mauritania, prompting Daddah to appoint military officers to positions in his formerly civilian government. Daddah was no fool, he understood that if he had any real threat, it was the military itself. By keeping it relatively weak and out of government, he could control it, but by strengthening it and bringing it in, his own personal grip was slipping. Even with significant foreign loans to prop up the floundering regime, discontent seemed to mount day by day. In February of 1978, he appointed Colonel Mustapha Ould Salek to commander of the armed forces. On July 10th of that same year, the appointed commander initiated a coup and imprisoned Daddah.

Aftermath

Mustapha himself was… Not a good leader. He squandered every opportunity given to him. The war with Western Sahara continued, he cared little for the black African population, he tried to restore stronger ties with France and ultimately, the coup-leader himself was subject to a coup on the 6th of April 1979, less than a year later. In August of 1979, under the new leadership, Daddah was allowed to flee into exile in France, who for some reason took him in. While there, he formed the humorously named ‘Alliance for a Democratic Mauritania’. The new leader, Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidalla, actually began pulling out of the Western Sahara conflict, but was in no less an unstable position. Numerous coup attempts failed to unseat him, particularly after he severed relations with Morocco in 1981.

Under his leadership, he attempted to bring about a multi-party democracy, only to then attempt yet another dictatorship after a failed coup attempt. He instituted Sharia Law as the new rule of governance, backing away from the tacit ‘socialist’ arguments of his predecessor. Slavery was declared abolished under his rule in November of 1981, the last country ever to do so, though the practice widely continued.

In 1984, he announced that Mauritania would recognize the Polisario Front as the legitimate government of Western Sahara, which promptly led to yet another fucking coup in December of that year. The new leader stayed in power until 2005, when he also got kicked out by a fucking coup, but now we’re way beyond the scope of what we’re meant to be talking about. …If you must know, yes, there was another one just four years later too. So that’s that. The history of what was at least the first Mauritanian dictatorship. The first independent one anyway. Most certainly not the last, but ah well. Tales such as this were relatively common across post-colonial Africa, alas. Whether this was due to the unresolvable tribal conflicts, meddling from foreign powers, an instability that disallowed any alternative or whatever else is for academics more skilled than me to decide. What it does at least make for is quite a fascinating piece of history.