I’m sure we’ve all daydreamed about owning a time machine, and wondering where we’d go if we had Dr Who’s Tardis for a week.

Obviously, first off would be a quick jaunt to the Jurassic age to bother some dinosaurs, followed by a trip to the year 3000 to see if people really do live underwater (and just how fine your great-great-great-granddaughter really is).

After these two essentials, the rest of my itinerary consists of those strange turning points in history, when one era dissolves into another, throwing up a short period of unfetter creativity and hedonism. Think the dying days of the Roman Empire, a time when the art of hosting orgies reached its throbbing, writhing zenith. Or Germany’s Weimar years, when “degenerates” of all stripes drank and sang in the Berlin cabarets as Hitler’s brownshirts marched outside.

The trouble with these eras is that they’re only really identifiable in hindsight. As any old hippy will tell you, anyone who claims to remember the Summer of Love probably wasn’t there, or at least not taking enough drugs.

Obviously, you can occasionally chance across such a time, when you arrive in a place and feel the buzz in the air, detect a certain bounce in people’s movements, and almost smell the ripeness of possibility in the air.

But if you go looking for it, you’ll almost certainly arrive too late; when the transformative period has been ossified by the arrival of Starbucks, Visigoths, gentrified warehouse conversions, or Nazis.

But I got lucky once, and that was when I accompanied semi-mythical travel creature Gareth Johnson on a research trip to Iraqi Kurdistan.

Many people asked why I’d want to visit such a place, and why Young Pioneer Tours would even consider taking paying guests into such a cursed land. Before setting off it was easy to reel off the region’s attractions: Ancient monuments from the dawn of time, eerie remnants of its tragic modern history, distant vistas of active battlefields, unparalleled scenery, and a famously hospitable local culture.

Many people asked why I’d want to visit such a place, and why Young Pioneer Tours would even consider taking paying guests into such a cursed land. Before setting off it was easy to reel off the region’s attractions: Ancient monuments from the dawn of time, eerie remnants of its tragic modern history, distant vistas of active battlefields, unparalleled scenery, and a famously hospitable local culture.

We were met at the airport by Pete, an Australian chap teaching at an international school in Erbil, the capital of the region. We were already pretty burned out after a series of connecting flights before the final leg from Doha. Then, after flying over endless crinkled mountain ranges we reached our destination, and began to corkscrew down to earth, like a falling sycamore leaf. The usual long steady descent isn’t practical in Kurdistan, a smallish region surrounded by nutters with rocket launchers.

“Alright boys,” said Pete. “Let’s getting going, I’ve got us a table at the pub quiz.”

Of all the things I hadn’t expected to do on my first night in Iraq, answering questions about Scottish rivers and Russian history was high on the list. As it goes, we won… so our entire bar bill was quartered and we went home with a keg of beer. Off to a good start.

To be fair, there wasn’t that much competition, just a few teams of expats and their local friends. The T Hotel and its sports bar have seen much busier times.

The bar was one of many in Erbil that sprang up after the region won a degree of autonomy in 1992 and thirsty oil contractors began to pour in. With this wealth, grand plans were made for the city, which expanded rapidly from its ancient walled citadel. An ambitious road system was laid out in the form of a spoked wheel and hotels led the way in a remarkable construction boom.

Just as this new metropolis was beginning to take shape, oil prices collapsed. Developers got cold feet, leaving a landscape of swanky hotels surrounded by the skeletons of half-completed tower blocks and empty fields. However, not everybody fled; there is a resilient expat community here that the hotels and bars continue to serve.

Of course, we always like to do our bit to support struggling industries, so we made the most of our cut-price victory drink deal.

We had big plans for the following day — a road trip into the south of the region. This would have taken us along the indescribably scenic Hamilton Road, with visits to Saddam’s crumbling palace at Amadiya, a tour of Halabja, scene of the dictator’s infamous gas attack, a peek over the Iranian border at Tawela, a night in the fascinating city of Sulaymaniyah before a return drive via the recently liberated city of Kirkuk.

After we’d crawled from our beds at about lunchtime, we conducted a brief feasibility study before concluding it wasn’t going to happen that day. This research would have to be a job for another visit. We had a chat with our tame taxi driver, and he agreed a price on ferrying us around the sights of Erbil.

The city has good claim to be the oldest continually inhabited place in the world, with evidence of up to 10,000 years of occupation. The citadel sits on a weirdly steep hill that looks a little like Ayer’s Rock. However, this isn’t a natural formation, but rather the result of thousands of years of building mud-brick houses on top of the remains of demolished mud-brick houses.

The city has good claim to be the oldest continually inhabited place in the world, with evidence of up to 10,000 years of occupation. The citadel sits on a weirdly steep hill that looks a little like Ayer’s Rock. However, this isn’t a natural formation, but rather the result of thousands of years of building mud-brick houses on top of the remains of demolished mud-brick houses.

There’s nothing much to see up there at the moment, except for the views. As soon as the oil money started to flow, the government rehoused all the residents (apart from one family — can’t lose that “continuously inhabited” record) and got to work restoring it. As with the rest of the city, this came to an abrupt end when the wells stopped pumping.

More lively—but only slightly more so—are the bazaars at the foot of the Citadel. Only somebody who has visited a market in the Islamic world can really understand the true meaning of “hard sell”. Experienced visitors will have learned to stare straight ahead and only glance surreptitiously at the goods on sale to avoid being dragged physically into the stores.

However, in Erbil the storekeepers didn’t seem remotely bothered about making a sale. Walking around a largely silent bazaar, being studiously ignored, is perhaps the closest you can get to the sensation of being invisible.

Even when I stopped and picked up some bars of Aleppo soap (this was Cleopatra’s favourite brand and only went out of production, for obvious reasons, last year) the storekeeper lounging at the back of the shop showed no interest in serving me. Eventually he muttered “ten dollar” and, knowing I wouldn’t buy at that price, shut his eyes and pretended to sleep.

We were trying to find a legendary store where foreign fighters hoping to join the Kurdish army, the Peshmerga, come to buy their kit — everything from water bottles to AK47s. However, we kept finding ourselves walking past the same old stores, so we decided to come back another day with a guide. In the meantime, it was time for a drink to wash away the last traces of hangover.

We’d been assured it was easy to find the centre of the bar area. “You’ll know you’re there when you see the Virgin Mary”, we were told. And sure enough, as soon as we saw her looming over a pleasant little green park we began to notice signboards advertising Tuborg, which is obviously the beer of choice out here.

We’d been assured it was easy to find the centre of the bar area. “You’ll know you’re there when you see the Virgin Mary”, we were told. And sure enough, as soon as we saw her looming over a pleasant little green park we began to notice signboards advertising Tuborg, which is obviously the beer of choice out here.

Before settling down somewhere, we decided to have a quick look round an off-licence. It was a drunkard’s dribbling dream, an amazing range of booze from across the planet. I bought a bottle of Assyrian gin to take back to Pete’s, and Gareth bought a bottle of some sort of fancy vodka, which he reckons is hard to come by anywhere in the world.

With supplies bought, we crossed the road to a place with the promising name of “Hotel Classy”. It seemed ok and had decent wifi, but the prices were a bit steep, so we decided to just have a couple of drinks and move on.

When the bill arrived it was obvious we’d been ripped off to the tune of about 100 dollars. The manager was summoned, and he explained that the small bottles of complimentary water that had greeted our arrival weren’t free. “OK. But they weren’t 1 litre, as it says here. And the price of the drinks are more than on the menu.”

“Ah”, replied the manager. “The menu is wrong. Sorry about that.” There then followed a heated debate about the ethics of the hospitality trade and the doubtfulness of the man’s parentage, before he agreed to amend the bill.

We did consider moving on to some less “classy” places, but decided to head back to Pete’s for a sensible evening and an early finish. After a delicious supper cooked by his wife Rosie, we sat out on the balcony for a nightcap in the cool evening air.

Somehow, with conversation freewheeling between politics, philosophy and the perfect pizza, the evening lengthened, and it came as a shock to be summoned by my alarm clock for an early start. Today we’d planned a day in the north of the region, and this time we really couldn’t back out.

As we crawled out into the morning sunshine, our taxi driver was waiting. “What happened to you?” he asked with a look of concern, evidently innocent to the effects of hangovers. “Are you OK?… your eyes, my God!” We assured him we were fine, just a little tired, and ready to get going. “But Gareth,” he said, “you have to wear long trousers at the Yezidi temple.” Gareth’s room was on the third floor of the building so, huffing like a ruptured elephant, he stomped off to change.

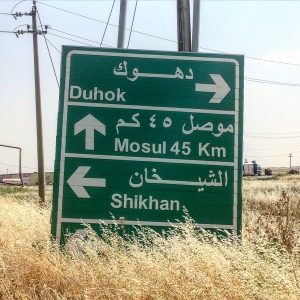

When he returned our driver started the car. “Do you have your passports? There will be many roadblocks…” Gareth, perhaps one of the world’s most experienced travellers, didn’t. And so off he stomped again, as much unlike a ray of sunshine as it’s possible to be. “Is he OK, he is so angry!” said the driver. “He must be very, very tired.”

I’d like to describe the scenery of the three-hour drive to Lalish, the sacred centre of the Yezidi religion, but I slept all the way. I awoke when I heard the crank of the handbrake, and from the cool fresh air I could tell we’d gained some serious altitude to arrive in a place that some consider to be the location of the Garden of Eden.

The Yezidi faith was largely unknown until the so-called Islamic State (or Daesh, as they call them here) started killing the men and abducting the women as sex slaves, but they’ve been around for a very long time. Although they are monotheists, they believe God placed the world into the care of seven angels, the chief of whom was Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel. This despotic entity caused both good and ill to befall mankind, and eventually fell foul of God, who banished him to the flames of the underworld. However, his grief and remorse were so great his tears doused the fires of hell and he was eventually reconciled with God.

Due to the obvious parallels with the story of the unredeemed Satan, they have long been accused of devil worship. Of course, they strongly deny this, even though the first thing you see as you approach their holy-of-holies is a dirty great black snake curling around the doorway.

Due to the obvious parallels with the story of the unredeemed Satan, they have long been accused of devil worship. Of course, they strongly deny this, even though the first thing you see as you approach their holy-of-holies is a dirty great black snake curling around the doorway.

Inside, the temple is very much like one of those interactive activity centres, like The Crystal Maze, that people go to for team building days or stag parties. Each dimly lit room presents a fresh challenge, usually involving some sort of manual dexterity. The “game” starts at the doorway, where you have to hop over the threshold to avoid disturbing a sleeping angel.

In the first room there are a number of pillars with bolts of fabric tied around them. The idea is that each of these represents a wish left by a previous visitor, which you fulfil by untying. You then retie it elsewhere, leaving a wish that a future visitor will help come true. Simple stuff, but there did seem to be a message about altruism behind it, albeit more humanist than religious.

You then hop over another threshold into room with a large granite block offset to one side. Again, quite simple this one, just walk around it seven times. The third room is more tricky. Standing on a well-worn part of the soot-blackened floor, you are given a gauzy piece of fabric and told to throw it over a bulbous stone sticking out of the wall. You have three chances, and if it stays put you get seven years of good luck. Gareth got it on his first go, I missed wildly. Another room was lined with ancient oil pots for a purpose I couldn’t quite make out, but it involved fire.

Our driver, being a devout Sunni muslim, remained outside the temple, but joined us when we climbed a steep slope to a small rock on top of a hill… which again needs walking around seven times (I guess this would be the physical round). Nearby were a group of Peshmerga soldiers, making the most of the open aspect to keep an eye on the Mosul valley far below.

They were remarkably relaxed, and keen to chat. They even let us play with their guns and invited us to a picnic. Sadly, we didn’t have time, so we wished them the best of luck and headed back to the car. As we left the driver looked troubled. “They are such nice people,” he said. “I don’t understand why everybody wants to kill them.”

After driving down the mountain, we made a stop at Khanis Gorge, an ancient Assyrian site with huge murals carved into cliffs overlooking a clear fast-flowing stream. Jumping in for a swim was too much to resist, and we were immediately attacked by tiny nibbling fish. I couldn’t help but think of the Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Could these be the most ineffective sacred-guardians-of-the-holy-tomb ever?

After driving down the mountain, we made a stop at Khanis Gorge, an ancient Assyrian site with huge murals carved into cliffs overlooking a clear fast-flowing stream. Jumping in for a swim was too much to resist, and we were immediately attacked by tiny nibbling fish. I couldn’t help but think of the Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Could these be the most ineffective sacred-guardians-of-the-holy-tomb ever?

Finally hangover free, it was back up the mountains to the Monastery of Alqosh, one of the oldest churches in the world, dating back to the seventh century. As we had technically crossed the border into Iraq, the monastery provided another great view over the Mosul plain. Vaguely, in the distance, we could make out little puffs of smoke rising over the flat brown landscape. “Drone strikes,” said our guide with satisfaction. “Over there is the frontline with Daesh.”

As we drove back down the winding road into the village of Alqosh, the driver asked if we wanted to stop at the village. “It is a Christian place,” he explained. “Sometimes when I have foreign guests they like to stop and drink alcohol.” Oh, well, why not? When in Rome, and all that.

The “alcohol” (or beer as it’s sometimes known) was sold by a small family-run shop with a charming little garden out the front, crowded with benches and whimsical cast concrete statuary. Nearby was an ancient cemetery, a small hillock bristling with crosses. We discovered that only 18 months ago the village had been deserted when Daesh advanced to its very outskirts.

Today, everyone is quite relaxed, they’re in safe hands with the Peshmerga — particularly now the Yezidi Women’s Brigades are in active service. These fighting furies are particularly effective as the Daesh believe that being killed by a woman disqualifies them from a martyr’s death, so no 72 heavenly virgins for them.

It was late when we got back to Pete and Rosie’s, so we hit the balcony, for just one little nightcap…

Just as well we didn’t have much planned for the next morning. We’d arranged for our driver to show us around the bazaar and some other sights of Erbil that we failed to find on our first day. He told us he was busy, but his father could take us. We double checked that he knew what we wanted to see — the military store and a supposedly famous “Ali Baba” antiques shop. “Yes, yes, he understands. He speaks no English, but I have told him.”

Just as well we didn’t have much planned for the next morning. We’d arranged for our driver to show us around the bazaar and some other sights of Erbil that we failed to find on our first day. He told us he was busy, but his father could take us. We double checked that he knew what we wanted to see — the military store and a supposedly famous “Ali Baba” antiques shop. “Yes, yes, he understands. He speaks no English, but I have told him.”

The old man arrived on time, and drove us slowly around the outer ring road to show us the sights. He was particularly proud of a brick-built minaret, which just looked like a stubby Victorian factory chimney. We seemed to drive past it several times. We parked near the market, and then discovered that the man walked even slower than he drove — it was like the slow motion bit at the end of Chariots of Fire, but without the running.

After about 20 minutes we’d barely entered the bazaar, when he motioned for us to “wait here” and disappeared through a side entrance. It soon became apparent he’d gone off to pray. Presumably he had quite the shopping list for Allah, and it seemed an age before he drifted back through the door and floated off, very slowly, gesturing for us to follow.

It was a bit frustrating, but we thought at least we were going to find the Kalashnikov ’n’ Karry store. But no… he took us to the soap stall where the storekeeper glared at me from the shadows.

We both then started acting out that we wanted to see guns, holding out two fingers and shouting, “bang bang!” I tried to do a machine gun impression, but it just sounded like a flatulent goat. Gareth managed a much better approximation, along with a quite harrowing death scene.

“Ahh!” said the old man, his finger slowly inching skyward in a show of dawning recognition. “Ok, ok.” And off we sauntered, with a renewed sense of purpose. Eventually, he stopped at a household goods store and slowly scrutinised the array of kettles, buckets and transistor radios. “Ahhh!” he said, triumphantly, and very slowly picked up a torch.

Dumbfounded, Gareth and I returned to miming our bloodcurdling battle scene, attracting quite a crowd of curious onlookers. Eventually a passerby said something in Kurdish to the old man, pointing at the flashlight that he was still holding out to us.

“Ahhh!” he said, and off he trundled. Just minutes later, he reached the adjoining store. “Ok, Ok,” he said, holding out a slightly larger torch, but this time with a flashing mode.

And with that, we gave up. We could have persevered, but we had a pool party to get to.

It was at this event it dawned on me that I’d chanced across one of those rare moments of history that I’d love to visit in a time machine. Here we were, just 30 miles from the frontline, being deafened by cheesy house music. The locals—men and women—were knocking back drinks under a hot afternoon sun, throwing each other into the pool, splashing each other, dancing (arms up, hips shaking) and generally laughing and laughing until they were hoarse and exhausted.

It was at this event it dawned on me that I’d chanced across one of those rare moments of history that I’d love to visit in a time machine. Here we were, just 30 miles from the frontline, being deafened by cheesy house music. The locals—men and women—were knocking back drinks under a hot afternoon sun, throwing each other into the pool, splashing each other, dancing (arms up, hips shaking) and generally laughing and laughing until they were hoarse and exhausted.

The three of us just sat and watched, trying to take it all in and commit the scene to memory. For the first time in my life, I felt moved to record a few seconds of video on my phone, such was the impression it made on me.

It was fascinating to watch for an hour or so, but the music was grating and the beer expensive, so we decided to head into the city’s Christian Quarter for a final-night pub crawl.

The neighbourhood was entirely different to the rest of the city, much more European with well-ordered shops and sensible pavements. The options for drinking were either hotel bars—empty and overpriced—or places that may or may not have been knocking shops.

These were very much like bars you might find in Eastern Europe. The walls were festooned with tattered Christmas decorations and luminous scenes of tropical beaches. The tables were topped with chipped formica, and the service was from heavily-made up and well-fed ladies. Before taking drink orders, they slowly and formally shook each of our hands, smiling and bowing slightly as they welcomed us.

Throughout the evening, we watched the response of the locals to this greeting, which usually involved giggling, blushing, and squirming. Perhaps naively, we concluded that such was the limit of their “service” — a smile, and briefly holding hands with a real-life lady, who isn’t a relative.

For all that the young people at the pool party are hoping to forge a new society, a new nation of Kurdistan, it’s still a very old-fashioned and unaffected place. I don’t think our driver ever worked out that our disheveled morning appearance had anything to do with our consumption of booze, and his father obviously couldn’t conceive of why anyone would want to look at a gun. I guess he’s seen more than enough of those for one lifetime.

But to see a place in a state of flux, where the cool kids are partying in the shadow of the world’s oldest settlement, where holding hands is a sexual service while women take up arms to avenge their sisters, to see a small corner of the Middle East where different religions live side-by-side, is a bit special. The time to visit Kurdistan is right now. Before the oil starts to flow again. Before the dark forces of Starbucks and McDonald’s overwhelm it and tread its history into dust.

With many tours to Iraqi Kurdistan scheduled every year, don’t miss out on this unique adventure!

Got questions about the tour? Is it safe? Do I need a visa? How can I join? Get in touch for answers: