History has no human beings who can claim an entirely unquestioned legacy, whether this is positive or negative. The past, however, is littered with countless figures who have contentious, controversial legacies that are discussed long after their death. Islam Karimov, who ruled Uzbekistan from 1991 until he died in 2016, is an excellent case in point of this.

Some in the country credit him with holding Uzbekistan together and overseeing the continuation of a secular state. In contrast, though, he was routinely accused of egregious human rights abuses and was described as one of modern history’s most brutal dictators.

While it has been almost a decade since the end of the Karimov, knowing about him is essential to understanding Uzbekistan, both historically and today.

And with tourism to the country having taken off massively – and only set to increase in the coming years – we wanted to give a comprehensive breakdown into arguably the most influential Central Asian in the post-Soviet period.

Who was this guy?

President Islam Karimov became the First President of the Republic of Uzbekistan in 1991, when he declared the country independent after the failed August Coup in Moscow. He ruled the country with an iron fist until dying in office in September 2016, exactly 25 years after taking up the mantle as president.

Having seen the implosion of civil society and economic meltdown in Russia throughout the 1990s, he refused to let Uzbekistan transition to a market economy.

In this sense, Uzbekistan can be compared to Belarus in the way that the Soviet Union was “fossilized” in both countries. State ownership, collectivization, and the closing of the domestic market to the rest of the world were the key economic characteristics of the Karimov presidency.

Unlike Belarus, however, the Karimov regime had some unique geopolitical challenges. It had to contend with challenges posed by Islamic militants, a spillover from the War in Afghanistan (which borders Uzbekistan), and a testy love-hate relationship with the West.

His ideology was thus formed by combining this centralized economic planning with a large dose of Uzbek nationalism. The latter is ironic, for reasons we will come onto.

What formed Karimov’s beliefs?

His early life, like many towering figures, is shrouded in mystery.

He was born in 1938 in Samarkand, a majority Tajik city that had recently been given to the Uzbek SSR by Stalin. While official government biographies emphasize his bonafide Uzbek credentials, he was rumoured to be half Tajik.

Much of his youth appears to have been spent in an orphanage, despite both of his parents appearing to be alive. He spent some time with his parents during the Second World War but, struggling to cope, they returned him to the care of the state upon the war’s end.

Growing up in an orphanage clearly affected Karimov’s politics and worldview. It made him a true son (and believer) of the Soviet system. All evidence suggests that his youth was spent speaking Russian and Tajik rather than Uzbek.

He would go on to become a mechanical engineer and gained a master’s degree in economics from Tashkent State University in 1967. This was a huge achievement for an orphan from the provinces.

While he had a brief (and mysterious) first marriage, he married his wife Tatyana in 1967. With her, he had two daughters, Gulnara and Lola, who would attract more than their fair share of attention over the years for their extravagant lifestyles and very public feuds.

Tatyana, who was of mixed Tajik and Russian Tatar descent, helped solidify Karimov’s position in Uzbek high society. Later, the first family would show severe discomfort with speaking Uzbek in public, preferring Russian. This only added another layer of complexity to the president’s political narrative as an ardent Uzbek nationalist.

His career path further reinforced his Soviet credentials, beginning with his role in the state planning committee in 1966. This was followed by a steady rise through the ranks of the Uzbek Communist Party. His experience overseeing centralized planning and the use of forced labour for cotton harvests under the USSR was to be mirrored in his leadership of independent Uzbekistan, where similar practices were maintained.

What happened when Uzbekistan became independent?

He became the First Secretary of the Uzbek Communist Party in 1989, just as the Soviet Union was coming apart at the seams. Rafiq Nishonov, his predecessor, had been in office for barely a year, yet fell out of favour with Moscow when he failed to quell ethnic riots in the volatile Ferghana Valley.

Karimov was seen as a safe pair of hands by the Soviets but showed his true colours after the August 1991 coup. This would be the final death blow to the Union. After initially backing the hardliners, such was his belief in the Soviet system, he saw the writing on the wall.

Realizing the chance to cement his place in history as the first president of Uzbekistan, he declared his country independent on September 1st, 1991. The nation was the second in Central Asia to break away from the USSR, just a day after neighbouring Kyrgyzstan.

Yet from that point, little changed in Uzbekistan, except for the introduction of a fervent form of Uzbek nationalism. As mentioned, Karimov’s background makes this deeply ironic, and it was likely an attempt to mask his distinctly Soviet, rather than Uzbek, identity.

He had a fractious relationship with Russia and only allowed Uzbek to be used as an official language in the country. However, Moscow generally stayed out of domestic affairs, and the sheer number of Uzbek migrants to Russia – as well as oil and gas exports – meant that the Uzbeks had to continue to cooperate. Karimov’s relationship with President Putin grew much warmer after 2005 when he kicked the Americans out of their airbase in the country and gave its control to Russia.

Regarding his relationship with the West, Karimov was considered a friend… until he wasn’t. Being located next to Afghanistan, he allowed the US to use an airbase in the southwest of the country. This was allowed in exchange for the international community turning a blind eye to the excesses of his government regarding human rights.

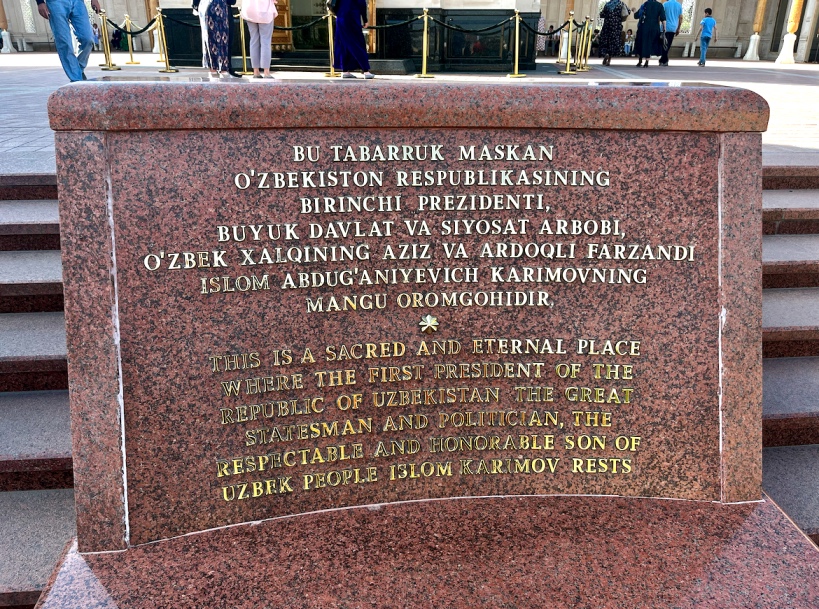

Interestingly, there were mainly older people here, coming as if on a pilgrimage.

This worked well until 2005, when even the United States could not turn a blind eye to the horrors of the Andijan massacre, which we discuss below.

And as the rest of the world opened up, Uzbekistan’s economy faltered yet more. He sealed the country off from the outside and had an especially tubulous relationship with neighbouring Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Foreign money was kept out, and the Uzbek currency, the sum, fell victim to hyperinflation and a rampant black market. His government’s refusal to print banknotes larger than 1,000 sum until 2013 – worth barely 50 cents even at the time – as well as a ban on other currencies meant that purchases routinely required carrier bags of bills. A joke still subsists in the country that Uzbeks are the fastest counters in the world, given the chaotic economic situation under Karimov.

His supporters, though, credit him with keeping the country together, and this is not a meritless argument. At the time, Uzbekistan easily could have faced total economic collapse, like in Russia, or have fallen into a civil war as neighbouring Tajikistan did.

Why is he so controversial?

It is impossible to mention Karimov in the West without mentioning “Andijan.” In 2005, his government opened fire on protestors in the western city of Andijan, one of the largest settlements in the Fergana Valley and long an opposition heartland.

While government sources claim that “only” 187 were killed, and that those protesting were Islamic fundamentalists, this is hotly disputed. There is little evidence that even a minority of participants were extremists, and the death toll is likely several times the official figure.

Either way, the massacre was the largest killing of protestors by their own government since Tiananmen Square and before the Syrian Civil War. This was a step too far for the Western coalition. They cut ties with the Karimov government accordingly, and his nation remained a pariah state for the rest of his premiership.

Several sources also mention horrific accounts of torture, extrajudicial killings, and general thuggery from the Uzbek security forces. The most infamous of these – of a man being boiled alive – is impossible to independently verify but has been repeated by several reliable sources.

However, the arguments those in favour of Karimov use are essentially the same as those used by realists to justify authoritarian regimes the world over. The world is not sunshine and rainbows, and however bad Karimov may have been, his government would always be better than the country becoming the next Afghanistan.

The comparison to Afghanistan is not an empty one. Not only do the countries share a land border, but for years the main threat to Karimov’s power came from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMO). The group was closely aligned with Al-Qaeda and operated out of Afghanistan, intending to establish an Islamic theocracy in Uzbekistan.

Karimov used the threat of the IMO to crack down on any expression of Islam, despite being of the faith himself. The call to prayer was banned, and anyone suspected of being a pious Muslim – an identity interpreted very broadly – was thrown into indefinite detention.

This would explain why his power base generally came from more secular Uzbeks, while his biggest opponents lived in the deeply religious Ferghana Valley.

Whether this merits all or even some of Karimov’s actions, though, is a moral and philosophical question that you must ask yourself. Even today, Uzbek society remains deeply split in this regard.

It is impossible to entirely answer the question of “did Uzbeks generally support Karimov or not.” However, my interactions with Uzbeks over the years led me to the following conclusion: while there was little love lost when he died – and many Uzbeks support the economic reforms of his successor – there remains very much an attitude of ‘better the devil you know’ when it comes to Karimov. Whatever his excesses, at least the country did not become Afghanistan.

What’s changed since his death?

Despite some concerns over Karimov’s lack of a successor, power transitioned peacefully after his death to Shavkat Mirziyoyev. He had spent 13 years previously as Prime Minister and promised to continue his predecessor’s legacy.

However, Mirziyoyev has gained a reputation as a reformer, which has made him popular with the international community. He opened the country up to international investment, largely ended forced labour in the cotton fields, and loosened many of the restrictions around religious expression in Uzbekistan. Relations with neighbouring countries have improved dramatically, and human rights abuses have, at the very least, been toned down.

His portrait, on sale here in a bookstore, can be yours for less than $20!

This does not mean the country is without challenges, however. Water shortages, overpopulation, and brain drain remain serious issues for the authorities to deal with. The country is still governed as an authoritarian dictatorship.

Mirziyoyev has also been criticized for his response to protests in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic home to the Karakalpak ethnic minority. In response to unrest after he tried to remove their right to secede, dozens were killed and hundreds injured. He has also been accused of backsliding on reforms and returning to some of the old Karimov policies.

Whatever the future holds for Uzbekistan, it will be fascinating to watch the country evolve… and especially the role that tourism will play in this.

Further sources:

Murder in Samarkand is a book published by Craig Murray, who was the British Ambassador to Uzbekistan between 2002 and 2004. Murray, a colourful figure to put it mildly, was removed from his post for being too vocal in his criticisms of the Karimov administration. This was in the context of the British Government trying to curry favour with the Uzbek government, in exchange for their support during the War on Terror.

Murray’s account provides fascinating, rare glimpses into what life was like in Uzbekistan at the peak of Karimov’s power. As well, the book platforms many of the controversies that arise when human rights are ignored in favour of geopolitical influence.

Meet the Stans is a 4-part documentary series by legendary travel journalist Simon Reeve. Despite being published in 2003, this provides a fascinating insight into Karimov’s Uzbekistan when he was most in favour with the West, before Andijan.

He explores the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, with the episode on Uzbekistan providing insights into the country’s complex history, politics, and culture. There is significant energy devoted to exploring the remnants of Soviet influence, the rise of authoritarian leaders in the region, and the diverse ethnic groups that call Uzbekistan home. Having been produced at a time when the country was essentially closed to the world – and with Reeve being accompanied by an Uzbek journalist living in London, allowing her to speak openly – this is the most thorough view of life under Karimov that can currently be found.

The Hated and the Dead’s Podcast on Islam Karimov delves into the life and rule of the leader. It expands on many of the points raised here, such as his Soviet background, brutal methods of control, and his legacy of repression, forced labour, and human rights abuses. Being produced just this year, this allows for a critical analysis of how Karimov’s leadership shaped modern Uzbekistan, and whether hindsight allows us to see his premiership through a different lens.