If you’re unfamiliar with the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), don’t worry. It’s one of those oddities of British politics that even the most devoted political enthusiasts would struggle to recall without a few notes and maybe a cold drink.

Founded in the early 1970s by Tony Cliff, a charismatic Marxist theorist who didn’t exactly play by the rules of traditional left-wing politics, the WRP wasn’t your average political party. But what makes it truly stand out in the annals of political oddities is its surprising, somewhat mysterious, and undeniably bizarre connection to Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya. Strap in, this is gonna get weird real fast.

Table of Contents

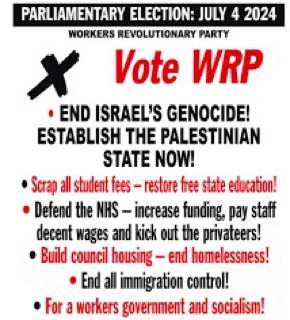

The Rise of the Workers Revolutionary Party

In the heady days of post-World War II Britain, political parties had a way of sprouting up like weeds in a neglected garden. The WRP, however, was a bit different. It wasn’t exactly your typical Labour Party type of socialist movement, nor was it your conventional Trotskyist group. No, the WRP was founded by Gerry Healy, who, for all intents and purposes, was a revolutionary with a side of charisma.

Healy was a self-proclaimed Marxist-Leninist and the WRP was his brainchild, a party built on the ideal of permanent revolution—not just in the UK, but worldwide. Essentially, the WRP’s idea of a good time involved stirring up political unrest at home while promoting Marxism in every corner of the globe. In theory, it was all about class struggle and overthrowing the capitalist system. In practice, it was a bit more, well some might argue all about the money.

The party began as an offshoot of the Socialist Labour League (SLL), a group originally formed around Healy’s leadership. The WRP quickly gained a reputation as one of the more radical Trotskyist factions, earning points for its unwavering commitment to Marxist orthodoxy, and—let’s be honest—some of the more peculiar tactics they used to spread the word. Think of it as a combination of street protests, obscure political pamphlets, and increasingly dubious international alliances.

Enter Muammar Gaddafi and the Libyan Connection

Now, here’s where things get interesting—and by interesting, we mean thoroughly odd. Around the same time the WRP was making waves in the UK, Muammar Gaddafi was in the midst of trying to establish his own version of a “revolutionary” state in Libya. By the 1970s, Gaddafi had already overthrown the monarchy and taken the country in an entirely new direction with his brand of Arab socialism, which he meticulously outlined in his Green Book. His government’s official ideology was anti-imperialist and anti-Western, so naturally, his regime attracted a number of left-wing groups from around the world looking for a strong ally against the influence of the United States and other capitalist powers.

Gaddafi was quite the master of playing the international political game, and that’s where the WRP came in. They weren’t just your run-of-the-mill revolutionary group—they were looking for backing from anyone with deep pockets who also seemed to hate capitalism as much as they did. Enter Libya.

While you’d expect a Marxist group to be keen on keeping ties with the Soviet Union or the Eastern Bloc, the WRP decided to hitch its wagon to Gaddafi’s more unorthodox brand of socialism. Now, you might be thinking, “Wait, wasn’t Gaddafi more about being anti-communist than pro?” Well, you’d be right… mostly. But Gaddafi’s regime was always happy to fund any left-wing group that opposed the West, so long as they didn’t question his absolute rule. And in this bizarre world of political alliances, the WRP was more than happy to accept Libyan funds in exchange for support.

The Libyan Connection: Funding, Arms, and a Shared Vision of Revolution

Gaddafi, ever the patron of unconventional causes, saw the WRP as a useful ally in his geopolitical struggle against the West. In return for their ideological endorsement, he opened the Libyan coffers to them. The WRP received financial support from the Libyan government, as well as training, resources, and sometimes even arms. It was a true marriage of convenience: the WRP got money to further their cause, while Gaddafi got a political ally in Britain—a country that was firmly entrenched in the Western capitalist bloc.

In the 1970s and 1980s, this strange partnership continued to grow. Healy and his followers were seen at various events, both in the UK and internationally, praising Gaddafi’s Libya for its revolutionary potential. The Libyan government even helped fund some of the WRP’s more ambitious political projects, including anti-imperialist propaganda campaigns and pro-Gaddafi demonstrations in London. The whole thing was a full-blown political love affair, although one that never quite seemed to make sense—especially considering the fact that Gaddafi’s regime was neither particularly Marxist nor particularly liberated.

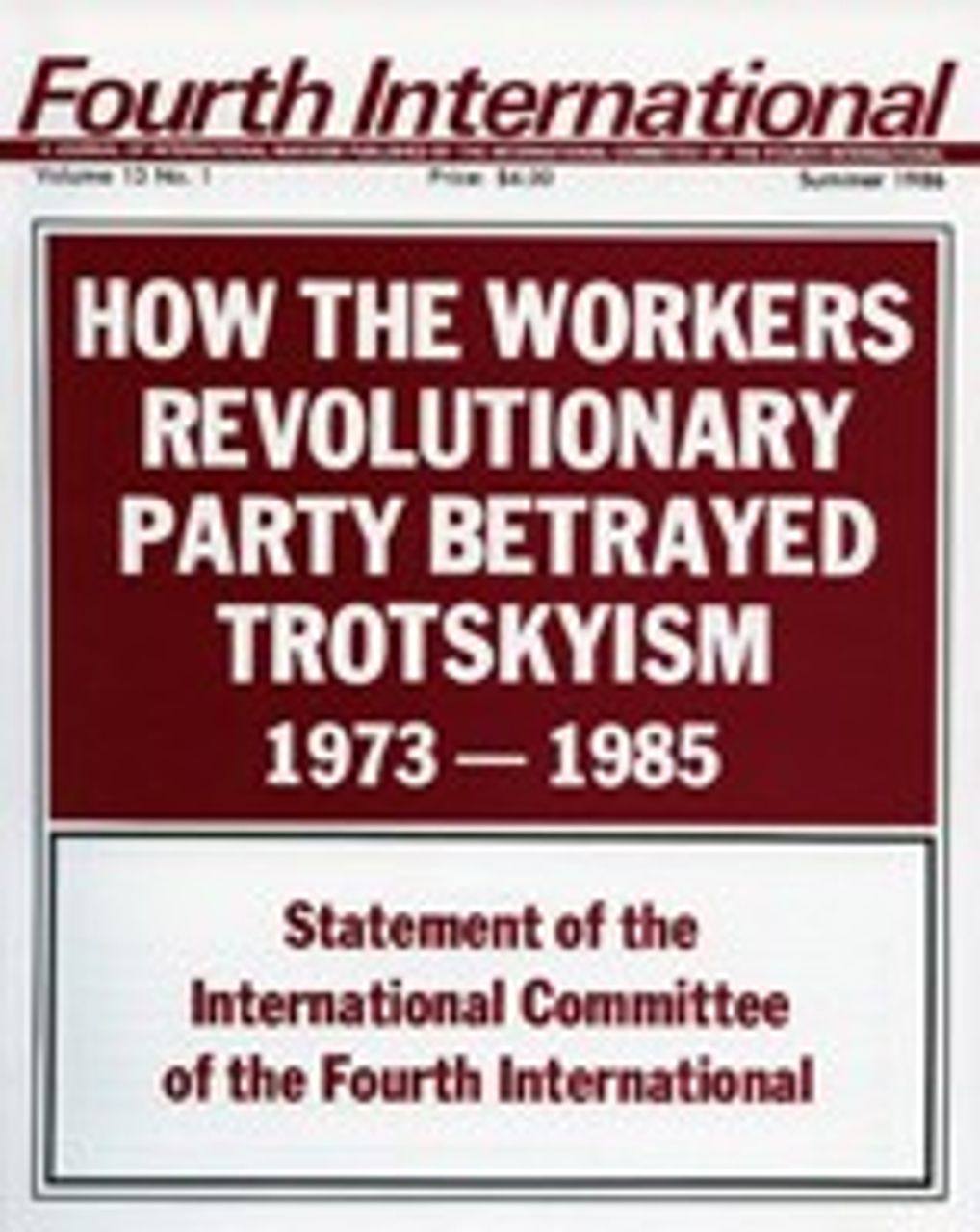

But of course, this oddball alliance wasn’t without its problems. In fact, by the mid-1980s, cracks began to show. The WRP’s increasingly authoritarian internal culture—not to mention their self-righteous tone—began to put off some of their more idealistic members. It became clear that the WRP’s brand of revolution wasn’t so much about freeing the working class as it was about making Gerry Healy and his associates rich and untouchable. Those deep connections to Libya’s oil money didn’t hurt either.

By the time of the 1980s, the WRP had become an almost laughable parody of its former self. Its funding from Libya was increasingly controversial, and many in the UK left-wing circles started to see it as just another group that was more interested in self-preservation than actually changing the world. But to give the WRP credit, they didn’t just let go of their Libyan connections—they were perfectly happy to accept the Libyan money until their very last days.

The Decline of the Workers Revolutionary Party

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was clear the WRP was in freefall. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Gaddafi’s ability to fund radical groups like the WRP began to wane. The Libyan link started to look less like a powerful asset and more like a mildly embarrassing vestige of a bygone era.

The WRP’s internal contradictions finally caught up with them. The controversial leadership, along with allegations of financial mismanagement, eventually led to the party’s disbanding in 1991. As the WRP crumbled, so too did its relationship with Libya. The whole debacle, from the Libyan cash flow to the revolutionary rhetoric that never quite materialized, ended in a whimper, rather than a bang. But it’s certainly a strange chapter in the political history of both the UK and Libya, a reminder of how unexpected alliances can form in the name of revolutionary causes—especially when they involve money and politics.

The Legacy of the Workers Revolutionary Party

Looking back, the WRP’s Libyan connection is a strange and, at times, amusing footnote in the broader history of radical left-wing politics. It was an example of an organization willing to make a deal with anyone in the pursuit of power—whether they shared common ideologies or not. For Gaddafi, it was another means of funding his revolution abroad.

For the WRP, it was a questionable partnership that ultimately didn’t lead to the workers’ paradise they’d imagined. Still, it’s a bizarre reminder of how ideologies, in their most extreme forms, can often lead to strange bedfellows.

Click to read about our Libya Tours.