If you’re just joining us, don’t forget to check out part 1 of this insanely long odyssey exploring the history and ideals of the infamous Khmer Rouge. In part 1, we explored how the Khmer Rouge came to be, the context of Cambodia and led right up to the official start of the civil war, with prince Norodom Sihanouk deposed and the military dictatorship of Lon Nol underway. Let’s just dive right in!

Vietnam and the USA Intervene

Lon Nol was a shit leader. Let’s just get that out of the way now, because you’re going to see a lot of clearly poor decisions and contradictory actions which inevitably spiraled the Cambodian conflict, like a shitty screenwriter making the villain more pointlessly evil to raise the stakes. To start with, Lon Nol almost instantly began scrapping Sihanouk’s long-standing policy of at least relative neutrality with Vietnam. Almost immediately after taking power in March of 1970, he gave Vietnamese forces in the country 48 hours to leave before he would begin military actions against them… Despite the fact that the Cambodian army was in no position to wage such a civil war.

Meanwhile the country instantly came into uproar. The traditional society had great reverence for its king and brutal street battles began, with Lon Nol’s brother allegedly being murdered in the streets before having his liver cut out and eaten as a sign of contempt for the coup. The Vietnamese recognized that they no longer had a reason not to support the Khmer Rouge, as their ally in Sihanouk was no longer present. Arms flooded in for them and the battles picked up in intensity. Lon Nol perhaps recognized that this was fast becoming a regular battle he could not win, so he instead opted to use atrocities to try and prevent a Vietnamese attack. Thousands of Vietnamese civilians in Cambodia were massacred, with one particularly notable incident on the 15th of April seeing 800 Vietnamese citizens slaughtered and dumped in the Mekong river to float down to south Vietnam. On the 17th, he appealed to help from the Americans to stop the rapid gains of an angered Vietnamese army.

Shortly after, the army of South Vietnam intervened on the side of Cambodia, forcing an exodus of many of north Vietnam’s most significant figures who now feared being overrun by a much-strengthened force attacking from multiple sides. Americans began to join the battle, at least to a certain degree, carrying out a few specialist operations and bolstering the south Vietnamese forces. By July of that year, the Vietnamese had mostly been driven out, but their leadership was not captured… And worse, the aggression from so many different powers on Cambodian soil proved to be an immense propaganda boom for the Khmer Rouge as the civil war started.

Formation of the FUNK and the GRUNK

So now that we have all that out of the way, let’s discuss the FUNK and GRUNK. What the fuck is the FUNK and GRUNK? Starting with the FUNK, it is the French acronym for the Khmer United National Front, a movement established by Norodom Sihanouk while in exile in Beijing, at least by the 5th of May 1970. This movement was an umbrella of anti-Lon Nol forces who wished to liberate the country through the civil war. As Sihanouk’s loyalists were not powerful enough on their own to form this group, they allowed others as well. The Khmer Issarak’s mentioned in the first part of this series formed a large part of the forces, naturally. These primarily consisted of Vietnamese-backed communists who saw an alliance of convenience. There was also the Khmer Rumdo, who were by this point a separate identifying faction of the Issarak forces who were far more loyal to Sihanouk and Khmer royalism. Thirdly… They had the Khmer Rouge.

It was, after all, unavoidable to recognize that the most well organized and equipped of movements at this time were the Khmer Rouge. They had been organizing insurgency for some time now and had been receiving Vietnamese military aid for even longer. They hit the ground running while royalist forces scrambled to assert themselves. As Sihanouk himself had taken refuge in Beijing, he gave his blessings to one of his worst enemies to operate this anti-Lon Nol force with him. Within the ten-member politburo of the FUNK, four were Khmer Rouge cadres, though notably Pol Pot was not among them. The chairperson was a Sihanouk loyalist, but as most ground-level power was consolidated in the Khmer Rouge, their influence began to wane.

Now, the GRUNK. What was that? It was the Royal Government of the National Unity of Kampuchea, the actual government in exile that the FUNK fought the civil war under the banner of. As the Khmer Rouge agreed to fight under this banner, they notably were accepting their status as ‘royalist’ forces and that Sihanouk was their head of state. Perhaps an alliance of convenience, but still a matter which confused people as to the true loyalties of the movement.

While Sihanouk himself was outside of Cambodia, as was the chairperson of the FUNK who served as prime minister, the third in command was not. This was Khieu Samphan, high ranking member of the Khmer Rouge who effectively served as the operational highest command within the country. It was impossible to sideline their influence. He served as vice prime minister and as minister of national defense. Most ministers in fact were Khmer Rouge, as the most qualified candidates under Sihanouk’s control had fled the country. They did not wish to be seen as a government in exile, so keeping as many figures within the nation was possible, although there were attempts to stem the overwhelming Khmer Rouge control.

The Khmer Rouge themselves kept many cards close to their chest at this time. Pol Pot had no official positions and was entirely unknown to be involved by the non-Khmer Rouge elements of the GRUNK. This would mark a persistent trend of secrecy where those truly in charge, along with their true motivations, were kept very unclear. This was useful for realpolitik, certainly, but could have disastrous consequences for a movement’s cohesion and perceived legitimacy… Though maybe I’m getting ahead of myself there.

The War Escalates

The Khmer Rouge had at one point been a rather fringe group, finding its support among oppressed minority groups and die-hard communists. Though even among those, many preferred to stay with the more independent Issarak groups. With Sihanouk’s backing and the founding of the GRUNK, their public support increased enormously. The Khmer Rouge were no longer the fringe movement, they were the movement of the people! They represented the leftists, the monarchists, pro and anti-Vietnam factions with more to boot! As other organizations had far less capacity to supply weapons and training, most rebels joined the Khmer Rouge outright and they spread through the country to lead the civil war.

Lon Nol, in his infinite wisdom, responded with further brutality. In contrast to Operation Menu, mentioned in the last article which was rather limited to the so-called Sihanouk Trail of Vietnamese forces in Cambodia, Lon Nol approved of the so-called ‘Operation Freedom Deal’ in which American bombing raids were authorized over vast swathes of the nation. While Operation Menu lasted for about a year, Operation Freedom Deal lasted from May of 1970 to August of 1973. And while Operation Menu killed a couple of thousand Cambodians, the devastation of its bigger brother dwarfed it. Anywhere between fifty thousand and a hundred and fifty thousand were killed in the bombings, which were largely indiscriminate and blanketed Khmer Rouge held territory. The total tonnage of bombs dropped was 250,000. In comparison, the tonnage of bombs dropped on Japan in the entirety of WW2 was a mere 180,000.

Now, how did this work out exactly? Well, at the peak of the operation, the Khmer Rouge were on the cusp of encircling the capital and with tens of thousands killed, many argue that it stopped the country from falling sooner! …But on the other hand, by prolonging the horror, the ugliness of the civil war was only to get worse. Refugees from around the country fled to Phnom Penh, swelling its size with an enormous refugee crisis, as well as destroying the farmland and driving out farmers, contributing to the rapidly growing famine.

Those who refused to or could not flee there inevitably joined the Khmer Rouge, many becoming sympathetic with their aims because whatever their issues with ideology, it wasn’t them indiscriminately blowing up their friends and family. The sharp schism in Cambodian society as a result of this and other atrocities can be argued as motivating the utter callousness of the Khmer Rouge towards the inhabitants of the besieged capital once it was captured. Now, the ideology of Pol Pot would inevitably have led to horrors anyway, but from the perspective of the rank-and-file guerrilla, it’s unquestionable that this affected their attitudes.

Vietnam Withdraws

As carnage grew and grew through the civil war, people began to seriously look for a way out. One of the most notable events was the Paris Peace Accords. Signed on January 27th, 1973, the accords concerned the Vietnam war primarily. The US by now were being crushed by poor morale, opposition back home and a general lack of success in Vietnam and used the accords as a means of withdrawing fully from that conflict. In theory, this was followed by a ceasefire in Vietnam, but that was broken by all sides within a day. What’s more important to the Cambodian tale is the other parts of the accords.

Most notable was the withdrawal of foreign troops from Laos and Cambodia. At this time, Vietnam was heavily involved in aiding the revolutions of both countries and America wanted some assurance that Vietnam wasn’t going to take the opportunity of lessened pressure to just roll over both. In another sense, it saved face for the US by gaining them a clear victory in some area, while most already knew the Vietnamese ceasefire would be broken sooner rather than later.

Vietnam complied and began withdrawing from Cambodia, which many pro-Vietnamese Cambodians saw as a stab in the back, drawing them closer to the clique represented by Pol Pot. Vietnam’s withdrawal also was a major cause of US bombings intensifying on Cambodian territory, no longer focusing primarily on a border region where Vietnamese troops were stationed. This too, was blamed on Vietnam as much as the US. Perhaps most damningly from the Khmer Rouge’s point of view was Vietnam’s choice to suspend arms imports to the Khmer Rouge as a means of forcing a ceasefire. The Vietnamese were, after all, aligned with the USSR, who at that time regarded the government of Lon Nol as legitimate. This angered the Khmer Rouge and increased the belief that the Vietnamese were their natural and eternal enemies.

So, what happened when Vietnam withdrew? …Well. Reports indicate that as Vietnamese forces withdrew, territory now held solely by the Khmer Rouge became much more brutal. Forced relocation of villages and execution of dissenters went up enormously now that there were no allies that needed placated, the civil war was now being conducted the way the Khmer Rouge wanted. Pro-Vietnamese Khmer Rouge cadres, often regarded as being far better behaved towards the peasantry, began to be purged now that their protectors had left.

The GRUNK too began to see itself purged of Sihanouk loyalists, becoming more openly a Khmer Rouge front, while still largely invisible to a peasant base that believed they fought for Sihanouk or any number of causes. In some cases, the Khmer Rouge actually went to war with itself, most notably between the ‘Eastern Zone’ and ‘Southwestern Zone’. The Eastern Zone leadership came to be regarded as ‘Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds’ by the more sectarian cadres of the Southwestern Zone. The differences were so great that they were noted to wear completely different uniforms, essentially being rival armies despite being of the same party. Calls for peace agreements were entirely ignored and so the war raged on, becoming more savage as time passed.

Phnom Penh Falls

The war trundled on with victory the Khmer Rouge growing ever more certain. Eventually, Phnom Penh was completely under siege, with every route in or out held under rebel control. The only saving grace was the inability of their forces to shoot down the American air supplies that kept the besieged city from effectively starving to death through the civil war. Although even then, food scarcity was rampant, medical supplies dwindled, fuel was practically gone, and morale had fallen through the floor. The army under Lon Nol still outnumbered the besieging forces around the capital at this time, but it didn’t matter, it was only a matter of time. Much like the fiasco that befell Saigon before America withdrew completely, foreigners and government ministers in Phnom Penh boarded American helicopters and got out of dodge before it was too late.

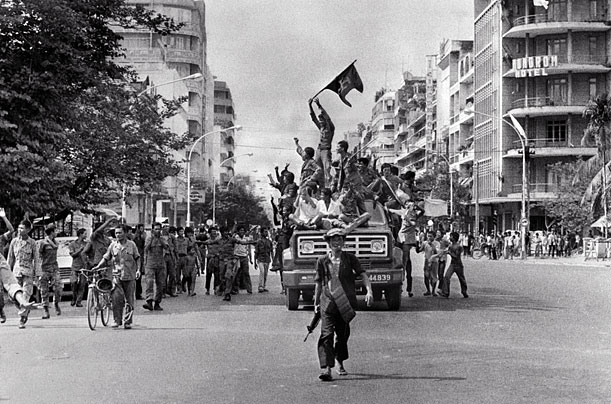

On the 17th of April 1975, it happened. The Khmer Rouge breached the capital. A last-ditch effort of the government to escape via a fleet of helicopters to set up operations elsewhere was simply too late, and their transport never arrived. What few helicopters were present were used to get some of the most significant figures out of the country and into exile in Thailand. An initial call to fight to the death was finally met with refusal and instead, bargaining began. Students and soldiers poured into the streets to greet the Khmer Rouge as though they were liberators, many as part of the obscure group MONATIO, believed to have been set up by Lon Nol as a broadly patriotic movement in hopes of securing some degree of power sharing and integration with the Khmer Rouge. The Khmer Rouge tolerated these ‘allies’… For a time. It’s believed that most were later rounded up and executed.

At this time, the number of Khmer Rouge forces in the capital was estimated at around 60,000. The population of the capital, meanwhile, was over two million. This was not a stable state of affairs. What’s more, with the Americans having fled, all shipments of aid that had been sustaining the capital had now halted, with what little food remained being sure to dwindle within a matter of days. It was here that the first truly infamous act of Khmer Rouge governance began, the emptying of the capital. All two million, within a matter of just a few days, were rounded up and forced to march in long columns down the roads out of the city and into the countryside. Every man, woman and child, every baby and every elder, even every hospital patient with zero regard for their ability to survive what amounted to a death march.

The excuse given was a fear of US bombings, but the real reasons were primarily two-fold. Firstly, that a mere sixty-thousand troops could not possibly have held off a revolt of two million should the situation deteriorate while the population was still so densely packed. Indeed, it was inevitably going to get worse. Moving them deeper into Khmer Rouge territory and splitting up the population would naturally help to rectify this issue. Secondly, the food situation. The country was in utter turmoil and despite most of Cambodia already being held by the Khmer Rouge, the population held by them was estimated at a mere one million, while six million still crowded in government-controlled cities, all of which were swift to follow Phnom Penh. The food production was only at a level to sustain the Khmer Rouge and the million or so peasants that they already controlled. With many fields riddled with explosives or simply unmanned, getting people to work to produce food was paramount. This makes sense and in a way, I grudgingly acknowledge that without this brutal march to the countryside, an even worse famine than what later followed could well have occurred… But still, these problems were in many ways of the Khmer Rouge’s own design, not helped by their refusal to accept assistance from others. They went it alone and were not prepared to do so.

With that, the streets of Phnom Penh were silent. Save for isolated battles with stragglers in the army, the rest of the Cambodian cities soon ceased resistance and melted into Khmer Rouge control, suffering the same fate as their citizens were marched out into the countryside. The civil war was over. The Khmer Rouge had won… And next, it’ll be time to talk about what followed. Join us in part three!