The French Revolution is an iconic piece of history. The masses of peasants storming the Bastille, the King and Queen captured, then beheaded in a public square. Revolutionary anthems, ‘Liberté, égalité, fraternité’ and all that. What is less talked about but no less important is the simultaneous revolution in far-off Haiti, the most profitable slave colony in the world. The Haitian Revolution was and remains a powerful and influential story.

Saint-Dominigue

To give a brief overview of Haiti’s history, we should start with Hispaniola. This roughly Belgium-sized island in the Caribbean is home to two modern countries, the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Back in the 1600s, even the powerful European empires weren’t exactly great at colonizing an entire territory, so it wasn’t uncommon for large portions of islands to be seized by one power, while the other portion to stay independent and then get snapped up by another force. Even the modern US saw much of this, with evidence of French colonialism especially apparent in the likes of Louisiana. Doesn’t sound like a British naming convention, does it?

For Hispaniola, this was pretty significant. Two thirds of the island were controlled by Spain and by 1659, the French had established themselves strongly in the other third. Perhaps owing to mutually shared religious beliefs and a powerful hatred of the British, the two nations decided not to go to brutal, bloody war over the matter and instead let bygones be bygones. In 1697, Spain formally recognized French ownership of the territory cultures began to develop separately, eroding the cultural links between native islanders in each portion.

Haiti is the modern name of the nation, after the Haitian revolution. Under the French, it was referred to as ‘Saint-Domingue’. This came from earlier Spanish colonialism, when the Island was broadly referred to as ‘Santo Domingo’ in reference to the Catholic saint, St. Dominic. The French name for their portion was merely the French equivalent of the Spanish name, with the latter carrying on into the modern day in the ‘Dominican Republic’.

For quite a few decades after the foundation of Saint-Domingue, little happened. There was an attempt to use the land to cultivate tobacco, which led to very little. Like a lot of colonies in this era, its practical uses were quite limited. Things began to change as sugar-cane began to be cultivated in large quantities in the 1680s, soon leading to an economic boom. It turned out that the land was perfect for such cultivation, so what was needed to take full advantage was an influx of labour. Where could a European power get such cheap and easy labour?

Pre-Haitian Revolution: The Slave Colony

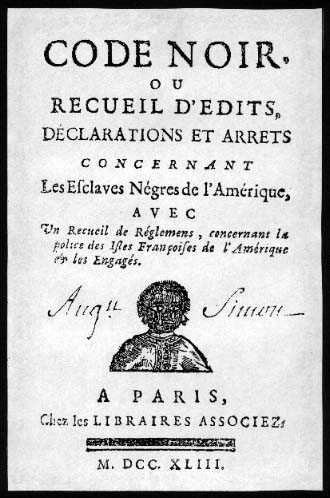

The French struck gold as slaves from Africa were imported into Saint-Domingue. By 1754, the population had bloomed to around 14,000 white Frenchmen, 4,000 free mixed-race citizens and 172,000 black slaves. By this point, the colony had earned the nickname ‘Pearl of the Antilles’ for its immense profitability. Over a hundred million pounds of raw and refined sugar were being produced and exported to Europe in this period, continuing to expand as modern industrial methods were applied. By the 1780s, 40% of sugar and 60% of coffee in Europe came directly from Saint-Domingue. Not even the combined British colonies in the Indies could compete, with expansion of the slave population continually blooming to increase output. Throughout its existence as a French territory, an estimated 790,000 African slaves spent time there, accounting for roughly a third of the entire Atlantic slave trade in its latter years.

Despite the colony’s incredible importance to the French economy, the slaves were treated viciously, perhaps even moreso than in most colonies of this era. While it’s possible that some exaggeration is present, a passage from the personal secretary of later Haitian leader Henri Christope goes as follows:

“Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars? Have they not forced them to consume faeces? And, having flayed them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and poniard?”

It’s no wonder that the Haitian revolution later came. Millions of Frenchmen subsisted either directly or indirectly from the wealth brought from this slave colony, though many millions more were living in abject poverty under a seemingly vicious and uncaring royalty. Unrest spread quickly through the nation and before long, the bubbling protest erupted in a glorious explosion of fury and revolutionary fervor that forever changed not only France, but the rest of the world as well.

The French Revolution

With the storming of the Bastille and uprising growing throughout the nation, the French monarchy floundered in its attempts to quell the revolution. Governor Marquis Bernard-René de Launay of the Bastille was decapitated and his head paraded through the city on a pike, prompting the royalty to desperately back down from attempting to violently crush the fervor. Government was restructured and the King accepted relegation to constitutional monarchy rather than absolute monarchy. A small price for of his head… At least for a time.

What at first seemed to be the end of things was in fact only the beginning. An amnesty granted to the royals sapped public support and soon the riots were sweeping the nation again, not helped by (accurate) rumors that fleeing nobles were trying to drum up support for a violent counter-revolution from neighboring nations. In their desperation to save the monarchy and the French state as it existed, drastic reforms continued, often under the control of revolutionary leaders themselves.

On the 26th August 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man was formally adopted in France, eliminating serfdom and forming the basis for France’s modern system of fundamental rights. The first article of the declaration set in motion the destruction of France’s slave colonies, opposed by some domestically and enthusiastically supported by many more in the French revolutionary sphere. The article read as follows “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.” The wording is vague, but to the people of Saint-Domingue, the message was loud and clear. All men are equal, social distinctions are an abomination and as French subjects, they are entitled to their fundamental rights.

Initially, the changes in Saint-Domingue were being led by freed mixed-race citizens who were full French citizens, but lacked many rights such as the ability to vote due to their race. A far cry from the later Haitian revolution. In October of 1790, Vincent Ogé, a free mixed-race citizen of Saint-Domingue who had spent time in Paris, returned home and demanded the right to vote from the colonial governor, his demand explicitly referring to the Declaration of the Rights of Man as its basis. The refusal of this demand led to him leading an insurrection in the colony, put down by early 1791. ‘Justice’ was swift and brutal, being sentenced to having his limbs shattered upon the ‘wheel’ before finally being beheaded. The reaction of the native Haitians could be best expressed by the advent of the Haitian revolution in August of the same year. There is a strong argument to be made that the Haitian revolution is an extension of the French.

Haitian Revolution Begins

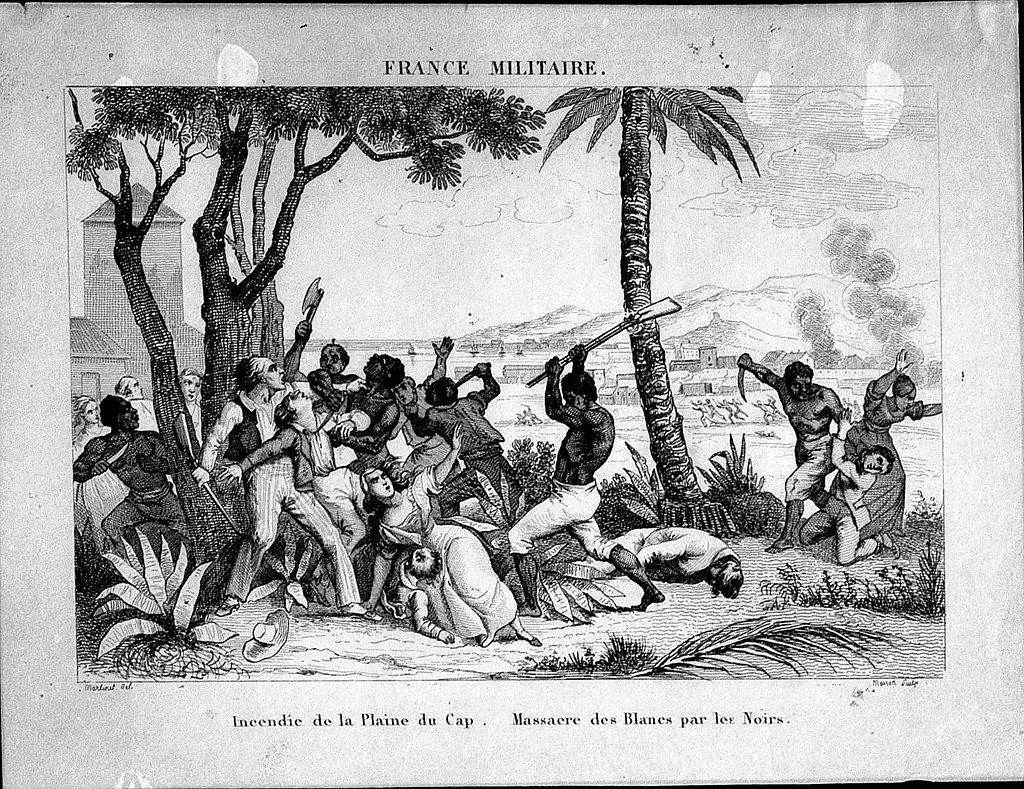

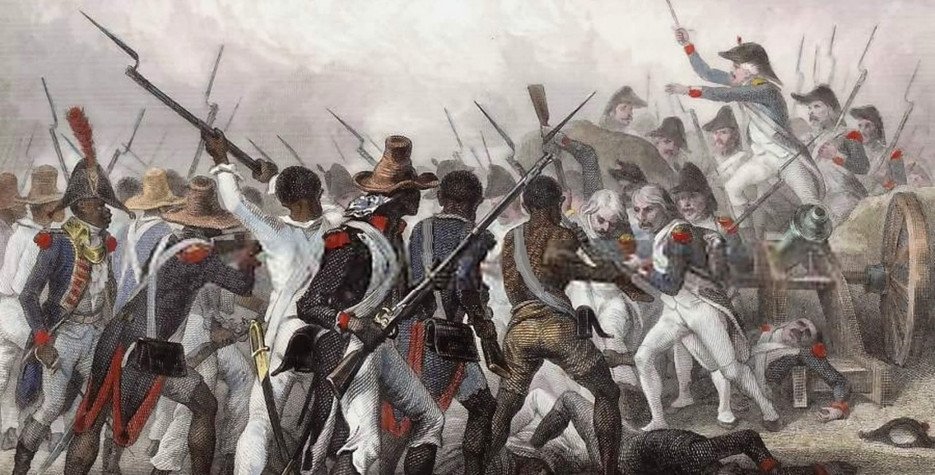

On the 21st of August, 1791, thousands of Haitian slaves attended a secret vodou ceremony. As a tropical storm swept the ceremony bringing lightning and thunder, it appeared as if an omen was influencing their decision. During the night, slaves suddenly began to slaughter their ‘masters’ and the colony erupted into civil war immediately. Within days, most of the colony had been overtaken by the numerically far superior slaves, with revolutionary fury leading to an orgy of violence and racial cleansing. With experience of white people for many being relegated entirely to brutal slave-masters, few were spared the terror and atrocities were rampant at the beginning of the Haitian revolution.

By September, the remaining, more well-armed whites had formed militias to try and strike back, but their successes were limited. Short of an outright invasion, impossible given the political situation back in France, the only solution was negotiation to prevent further bloodshed. The newly elected Legislative Assembly in France finally opted to grant full civil and political rights to freed men in the colonies. In March of 1792, 6,000 French troops were sent to the colony and a new governor was instated. Léger-Félicité Sonthonax made drastic efforts to try and save the colony, granting complete freedom to slaves in the north of the island in 1793. The intention for this was so that a military of both mixed-race freed men and former slaves could work together to quell rebellion, having a better representation than purely white and mixed-race soldiers who would still be seen as an entirely racist occupation force. Ultimately, this method did little to change the revolutionary tide.

One might ask why France itself would allow such a thing, but by this point, France had become a completely different nation. The 21st of September 1792 had seen the official abolition of the French Monarchy, forming the new French Republic. On the 21st of January 1793, King Louis was executed by guillotine and the monarchic, feudalistic remnants of France had been officially purged from existence. Control over France was increasingly held by radicals, in particular the likes of Maximilien Robespierre of the Jacobins who was increasingly open in his outright distaste for the practice of slavery. In 1793, a new constitution was approved by Robespierre and ratified by national referendum which would have explicitly outlawed slavery. Alas, it was not implemented. The Jacobin power in France was large but not absolute. Infighting between the Jacobins and the strengthened French bourgeoisie landowners was becoming increasingly strained. The culmination of all this, I’ll return to later.

Spain and Britain Counter the Haitian Revolution

I noted before that long before the French involved themselves on the island, the Spanish already controlled a sizable chunk of it. The island was of little use to them and there was a natural assumption that it was of little use to the French as well. As it happened, fortunes had switched sharply in France’s favour, so there was a feeling in Spain that France’s misfortune could be Spain’s opportunity. From the outset, Spanish Santo Domingo was used to house black refugees, provide material support to the rebellion and aided its followers. Despite this, Spanish involvement was, by necessity, quite limited. Spain had very little in the way of infrastructure in their region and could supply few troops. To involve themselves so openly, they required help.

Enter the British. As with so much of colonialism throughout the centuries, the Brits naturally felt a need to get involved somewhere. Sensing strong opportunity to grow their empire, Britain openly collaborated with French landowners in Saint-Domingue, with them recognizing British sovereignty over the colony in return for maintaining the practice of slavery. This action, among other things, led to France declaring war on Britain. Aside from simply seeking to gain further power, there was another reason Britain got involved. The Haitian revolution scared Britain shitless. If the most powerful colony in the Caribbean overthrew their white rulers and tried to establish an independent state, what kind of precedent did that set for everywhere else? What would later become quite a strong omen is this matter of precedent. The Haitian revolution wasn’t merely about Saint-Domingue/Haiti, it was about global colonialism.

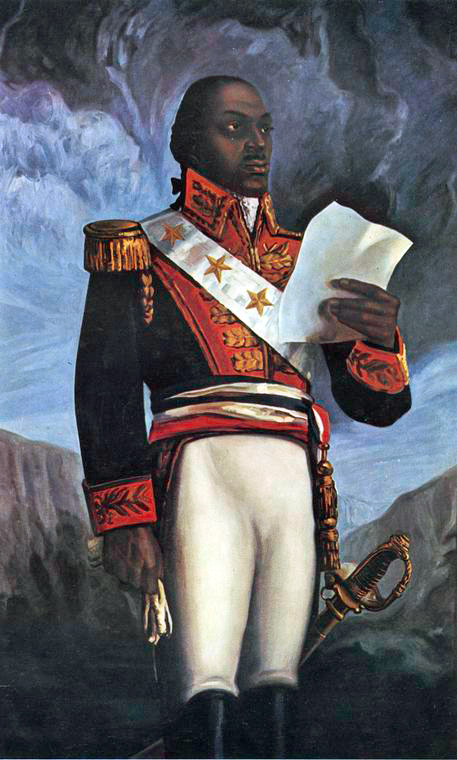

The initial British invasion was small. Hardly holding the necessary power to take over the island and thus only holding some coastal territory. This was followed by a Spanish incursion to the north, leading to famed Haitian general Toussaint Louverture formally becoming a Spanish officer and made a Knight of the Order of St Isabella. Such incursions were at this point, small. Even worse, they were poorly timed. An informal rule existed regarding war in this region which declared that war should only be waged between September and November, due to the comparative lack of disease spreading insects in these months. The British departed for the colony November 26 1793. You can guess how that went.

After the main British arrival in February of 1794, most gains were being made under the Haitian generals, who had knowledge of the land, culture and held the bulk of muscle. French forces on the colony were dwindling. The tide began to change rather abruptly as on the 6th of May 1794, the aforementioned Toussaint Louverture switched sides to ally with the French and crush the Spanish expedition. By 1795, the the Spanish ceded their territory to France and departed the island entirely, with Toussaint reportedly remarking his desire to exist as a full and free French citizen and for the island to be an equal partner with France rather than a colony. By this time, the Jacobins had been usurped and Robespierre executed, though the new government in France was at this stage still devoted to the promise to free the colonies.

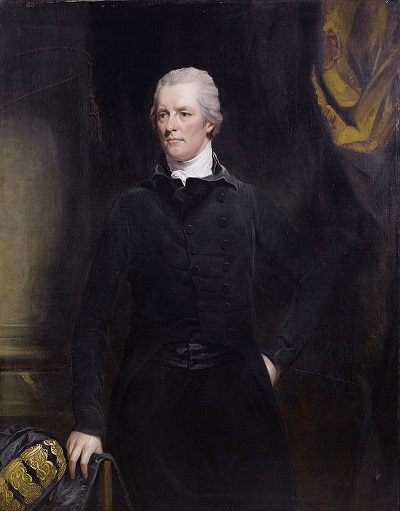

Back to the war effort, the British finally saw the toll exacted for their foolish timing on the island. Over the course of 1794, about half of the British forces were dead from disease and Haitian assaults. Of General Charles Grey’s main military force of 7,000, about 5,000 were to die of yellow fever. It appeared that Britain took this as a major blow to their pride, as what followed was one of the largest naval expeditions ever carried out by the British empire, with over 30,000 troops sailing for Saint-Domingue and even more to come over the following years in an expedition which lasted until 1798. The war was immensely unpopular and yellow fever continued to be the primary cause of death for those who went there, stunting efforts to quell the Haitian revolution.

With Toussaint making increasing gains, capturing more and more of the island, British morale utterly collapsed. On 31st of August 1798, the British formally signed an agreement with Toussaint promising to withdraw from the island on the condition that Toussaint not attempt to support revolution in Jamaica. The total cost to the British was four million pounds (in 1798 money) and approximately 100,000 dead or wounded.

Developments in France

We jumped ahead a lot, all the way to 1798, so let’s go back to France for a bit. In 1794, delegations of former slaves and slaveowners traveled to France to argue their cases for the future of the French colonies. Upon arrival, the former slave delegation was arrested, before being released on orders of the Committee of Public Safety, headed by Maximilien Robespierre. After receiving this delegation, the National Convention passed a decree to ban slavery on February 4th. The following day, he gave a speech outlying in no uncertain terms his feelings on the matter.

We want, in a word, to fulfill nature’s wishes, to further the destinies of humanity, to keep the promises of philosophy, to absolve providence of the long reign of crime and tyranny. So that France, once illustrious among enslaved countries, eclipsing the glory of all the free peoples that have existed, may become the model for all nations, the terror of oppressors, the consolation of the oppressed, the ornament of the universe; and that in sealing our work with our blood, we may at least glimpse the shining dawn of universal felicity. That is our ambition, that is our goal.

Maximilien Robespierre, 5th February 1794

In June of 1794, this was followed by a further decree to end existing slavery and had it ratified. The result in Saint-Domingue was overwhelming public support from the freed black ex-slaves. They had at last been assured that France would not attempt to enslave them again and their fury could be focused on the invading French and British, no doubt leading to the defection of Toussaint from Spanish loyalty to French. The Haitian revolution had changed somewhat, but not in character.

Alas, France was undergoing massive upheaval at this period. War was being waged on many fronts, internal purges were being conducted to prevent the return of monarchists or a new aristocracy, food shortages became rampant due to both the war effort and price fixing. The chaos of this period is what no-doubt ended the 1793 Robespierre-approved constitution, which would for its time have been far and away the most radically egalitarian constitution in the world. In July of 1794, factions within the French government had begun to fear Robespierre’s increasing power and the threat of falling victim to the next wave of revolutionary purges. A coup was orchestrated as the start of what would come to be known as the Thermidorian Reaction.

The term is a little obscure. Following the revolution, the old calendar had been thrown out and replaced with a new one. What was at this time 27 July 1794 in our calendar, corresponded with 9 Thermidor Year II. An order was issued to arrest Robespierre and after a brief internal conflict between Jacobin loyalists in the Paris Commune and the National Convention, which formed the bulk of the government, Robespierre and many of his associates were viciously arrested, injured and executed via guillotine the following day. What followed was a near civil war between Jacobin loyalists and what we can call the Thermidorians. This led to the ‘white terror’ in which numerous massacres were carried out against Jacobin loyalists, securing the power of the French bourgeoisie against the more radical revolutionaries.

On the 22nd of August 1795, the Constitution of the Year III was adopted in France. This rolled back many of the democratic promises of the Robespierre constitution, but nonetheless upheld the abolition of slavery. By October, there had been a royalist revolt put down by none other than Napoleon Bonaparte, future dictator of France. By the 2nd November 1795, the National Convention dissolved itself in favour of the far less democratic French Directory, a committee of five people. The impact of this on Saint-Domingue was negligible at first, but the Directory was unstable. Due to continued war from Britain, including naval blockades, none of this initially affected Saint-Domingue or the Haitian revolution but the start of what was to come was clear.

Perhaps most notable was the attempted colonization of parts of Egypt, at that time part of the Ottoman Empire. As well as holding strategic advantage for the war with Britain, Egypt was useful for sugar cane plantation, the same product that Saint-Domingue fared so well for. This idea was headed primarily by future French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte, with the Directory being largely uncertain about it, at least at first. To prevent the incursion being seen as purely colonial in nature, it was pitched as a scientific expedition with intentions to spread modern science and enlightenment ideas to the region, the warships being stocked with many acclaimed scientists from across France. Ultimately, this conflict came to little with the British crushing the French forces at the Battle of the Nile in August of 1798.

Contrasting to this, the Directory also aided revolutionary movements in other parts of the world, notably providing support to the 1798 Irish rebellion under Theobald Wolfe Tone. While the obvious purpose of this was to strategically undermine the British, with whom they were in conflict, the idea was pitched as an extension of the revolutionary potential of the French republic. By this point, the true universally liberating intents of the revolution were mostly dead and buried.

Haitian Revolution: The War of Knives

Returning at long last to the actual point of this whole article, we have the renewed stability of Saint-Domingue. At this stage, the territory was effectively led by Toussaint Louverture, the aforementioned general. While loyal to France in theory, the territory was little affected by the incredible turmoil back there. Saint-Domingue almost existed as an independent territory… With its own series of coups, wars and internal turmoils! Perhaps most notable to address is the War of Knives.

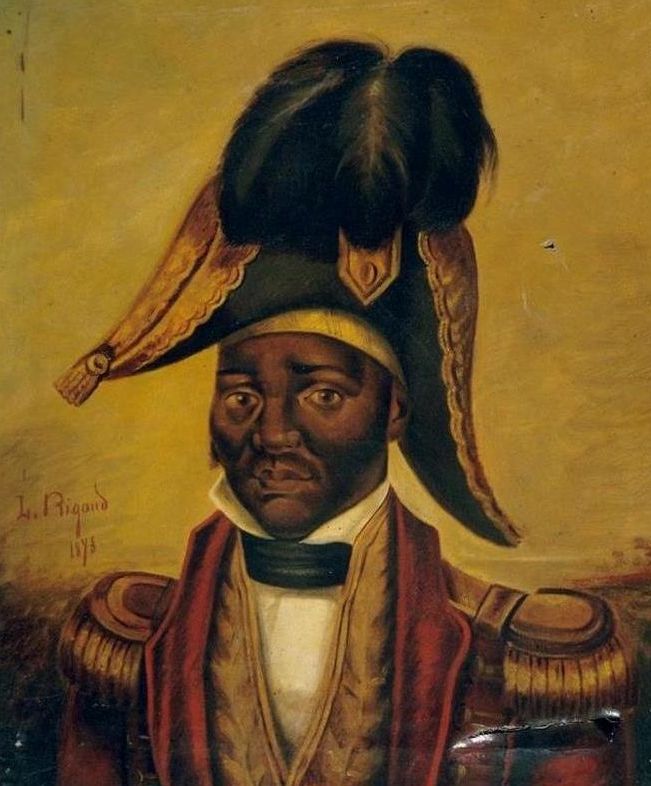

While Toussaint was undeniably popular and held significant control over the region, this power was concentrated in the north. Toussaint’s direct authority was limited, so in the south of Saint-Domingue, it was considerably easier to usurp his authority. André Rigaud was one such person who attempted to do just this. Rigaud was a mulatto, that is to say, a mixed-race Frenchman. His father was a famous French painter and his mother a slave. Due to his father’s influence, Rigaud was educated back in France and spent most of his life around white Frenchmen, who he came to have more solidarity with than the slaves of Saint-Domingue.

While Rigaud very much opposed slavery itself, he still believed in a racial caste system of sorts, with whites at the top, mixed-race just below and blacks at the very bottom. Naturally, this resulted in significant tensions when the battle against the British finally ended. With chances of a return to slavery essentially ended, a number of white Frenchmen decided to cut their losses and side with Rigaud, figuring that at least they’d hold some level of authority and respect in this system. Many of the mixed-race population in Saint-Domingue also sided with Rigaud, seeing it as their opportunity to rise to the top.

As Toussaint gained influence and power, the fragile stability began to collapse, with Rigaud and allies fearing complete black ‘domination’ of the island. In anticipation of the coming conflict, Rigaud acted first. Between June 16-18 of 1799, Rigaud attempted to secure his own position by slaughtering white Frenchmen in the coastal towns of the south. This primarily mulatto-led incursion was intended to set the stage for what followed, with discord sown in northern towns that Toussaint held comparatively little control of. Both sides operated in the name of the Haitian revolution, while simultaneously invoking the authority of France.

What followed was a swift spate of massacres and executions led by Toussaint as well as a letter sent to then American president John Adams, asking him to close trade with territory held by Rigaud, which was duly complied with due to Rigaud’s closer ties to the French government which was in a tense conflict with the US. Knowing that there was no peaceful end to such a conflict, Toussaint immediately launched a large counter-offensive on Rigaud’s territories, mobilizing around 45,000 black troops against Rigaud’s 15,000. Even more notable, an American fleet assisted in the conflict by bombarding Riguad’s transportation barges.

While Rigaud had been granted informal authority under the Directory, things suddenly changed and spelled the end for his ambitions. An emissary of France sent by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, who had recently performed a coup against the Directory, was sent in June of 1800. The emissary reaffirmed Toussaint’s position as general-in-chief of Saint-Domingue, demolishing Riguad’s claims to the contrary. By July, Rigaud had fled to France and Toussaint had claimed the entire island by August. Five months later, recognizing his advantageous position, Toussaint invaded Santo Domingo, formally owned by the French but de-facto still under Spanish administration. There was no resistance and Toussaint controlled the entirety of Hispaniola by 1801.

The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte

As Napoleon Bonaparte increasingly proved himself vital to the Directory’s ambitions, his own personal desire to consolidate power grew. Firstly, he wished to join the Directory itself. Alas, a rule within the Directory was that directors had to be at least forty years old, while Bonaparte was thirty in 1799. Nonetheless, he was an extremely popular figure in France. Being from Corsican nobility, he was supported to some degree by royalists, while the Jacobin remnants supported him due to his suppression of a royalist rebellion several years prior.

On the 9th of November 1799, a plan was set in motion. The Council of Ancients (Upper house of French legislature in the Thermidor era, who selected the Directory members) were summoned for an emergency meeting and informed that a Jacobin conspiracy had been uncovered. To assure security while measures were put in place, they were asked to put Bonaparte in charge of the French forces in Paris, to which they immediately agreed. This was followed by a similar meeting with the Council of Five Hundred (who selected the candidates for the Directory, which were then passed to the Council of Ancients).

Three members of the Directory were persuaded to vacate their posts, while the final two were arrested, leaving the Directory unable to meet and the government effectively paralyzed. Bonaparte met again with the two councils on the 10th of November, announcing the end of the Directory. While the Council of Ancients received him coldly, the Council of Five Hundred was far more outraged. Jacobin deputies within the council accused Bonaparte of acting outside of the law, a ruling of which would have allowed him to be executed immediately, just as Robespierre had been. Quickly leaving the building, Bonaparte told his men that he had almost been assassinated and the room was cleared by soldiers. What followed was the establishment of the Consulate which was to reign for the next few years.

The Consulate had its share of internal squabbling that is largely beyond the scope of this already lengthy article, but what’s important to know at least is that on the 7th of February 1800, a new constitution established unparalleled power for Bonaparte. While not yet an open dictatorship, the three existing consuls which existed to maintain some level of democracy were largely made superfluous, with only the First Consul, headed by Bonaparte, holding any real power. The new constitution did away with many fundamental rights granted under the revolution, with most regarding this as the true end to everything begun in 1789.

Saint-Domingue Expedition

Sensing a growing appetite for independence in Saint-Domingue, Toussaint’s arguments to the contrary increasingly fell upon the deaf ears of Napoleon Bonaparte. Saint-Domingue was an incredibly valuable colony and as France geared up to become an empire once more, independence as a result of the Haitian revolution could not be tolerated. What’s more, slavery was once again advantageous. The revolution in France by this point was dead and buried, so what did it matter if slavery was to return?

As a series of European conflicts finally came to an end, Napoleon finally found himself in a position to focus on internal affairs and appointed General Charles Leclerk (husband to Napoleon’s sister) to head an expedition to Saint-Domingue and re-assert French control. Initially, plans had been a lot more cordial. Merely to offer Toussaint a new position, not re-introduce slavery and establish a French governor as ruler of the island. By October, this plan was no longer on the cards, influenced strongly by a constitution drafted by Toussaint in July of 1801.

Napoleon himself had suggested drafting a new constitution for Saint-Domingue, but this was to be a constitution written in France. Toussaint, upon hearing the native Haitian’s fear of the re-introduction of slavery, instead appointed a local commission to draft a constitution. This constitution, drafted entirely by white Frenchmen, established Toussaint’s authority over the entire island, granted him governor-general for life status, the possibility of choosing his successor and affirmed the permanent end of slavery. This constitution was however still conservative, intending to appease Napoleon. Saint-Domingue was still affirmed as a French colony, Catholicism still prevailed over native Vodou as the state religion and slavery was still being accepted for non-French citizens. That is to say, those who were not already native residents of Saint-Domingue.

The constitution was received coldly by Napoleon, resulting in a shift of plans to an outright military incursion. 30,000 men were assembled for the incursion, including Rigaud who saw his opportunity for a political comeback. The initial attack was largely an undeclared trap, with some of the French forces landing on the island freely while others engaged in immediate conflict. Toussaint’s forces retreated into hard-to-reach areas and took many white hostages with them, while the French expedition under Leclerk held Toussaint’s two sons as hostages of their own. An ultimatum was issued, with the promise that Toussaint could become Leclerk’s deputy in control of the island if he was to surrender. After months more of brutal fighting, Toussaint finally surrendered and, true to his word, Leclerk restored Toussaint’s ranks by the start of May 1802.

Toussaint remained essentially retired, though even with him out of action, the brutality continued. Yellow fever ravaged the French forces and an opportunity to reassert authority returned. Toussaint warned his allies to be prepared for war, but some tipped off Leclerk to this growing threat. In June, Toussaint was lured to a trap, arrested and deported to Europe where he would later die, unable to see the full fruits of the Haitian revolution.

The Return of Slavery

On the 20th of May 1802, a law was passed in France which officially reinstated slavery to all French territories. Fury and outrage at this decree unified the native population of Saint-Domingue, who up until this point had been divided by a series of factions. An attempt to disarm the black population was met with further outrage and soon, the mulatto population were equally incensed.

By August of 1802, Leclerk’s black and mulatto forces were defecting en masse, diminishing French forces to between 8-10 thousand soldiers. Soon, realizing that his greatest enemy may well have lain in the black population of his own army, those black officers that remained were ordered slaughtered by Leclerk, with most being weighed down and pushed to the sea. Even loyal officers with no evidence of secessionist ideas were killed in this near act of genocide.

On the 1st of November 1802, Leclerk ultimately died of yellow fever like so many of the would-be colonialists before him. He was replaced by Rochambeau, who proved a vicious tyrant in his own right who allegedly ordered 600 pit bulls from Cuba and ordered them to never be fed, only subsisting on ‘negro meat’. This only furthered to anger the re-enslaved blacks and reinforce the continued Haitian revolution. By the 18th of November, 1803, the growing rebellions within Saint-Domingue finally routed the last of the French forces at the battle of Vertières, under rebel general Jean-Jacques Dessalines, finally concluding the Haitian revolution.

Independent Haiti

At long last, on the 1st of January 1804, Dessalines officially declared Saint-Domingue to be an independent state under the name of Haiti. He was named Governor-General for life and on the 6th of October 1804, was crowned Emperor Jacques I. What followed was a brutal purge of the white population of the island, essentially ethnically cleansing it and instituting a system of serfdom for the island. On the 17th of October 1806, Emperor Jacques I was assassinated and the island split into a kingdom in the north under Henri I and a republic in the south under Alexandre Pétion. Alexandre was eventually replaced by Jean-Pierre Boyer, who unified the nation after Henri I killed himself in 1820.

After this long and winding path, we have finally come to the end! For those of you still with me here, I’m guessing you have some serious interest in Haiti, its history and its culture. If so, then you should join us on our Haiti tour! For those also interested in learning more about Haiti’s later history, check out my piece on 20th century Haitian vodou dictator Papa Doc and his son, Baby Doc!