What is the difference between Somalia and Somliland?

After several months of living in Somaliland’s would-be capital city of Hargeisa, a friend from China messaged me asking if I was okay. The news that morning had been full of footage from Mogadishu. Hundreds of people had died in one of the country’s worst terrorist attacks.

“It’s okay,” I messaged back. “I live in Somaliland, not Somalia.”

By that point I was used to people making the mistake but his response was probably my favourite so far:

“Oh… I genuinely thought that was a typo.”

It’s hard to blame him. Africa has scores of disputed territories and separatist movements. The sheer fact that so many exist makes it less likely they will ever be recognised. Western governments say that recognition is a matter for the Africa Union, but few members want to accept new countries knowing that it will kick off territorial disputes at home.

Somaliland, however, is a little different. It was in fact at one point an independent nation… For the grand total of five days between its independence from Britain and its union with Somalia. Unlike other aspiring nations, the country it is technically part of has no official presence there. Somaliland functions as an independent country complete with its own government, currency and military, even though it has remained unrecognised by the international community for over twenty years.

So how did this happen?

The Somali people have spread across five regions in the Horn of Africa: Djibouti, Somaliland, Somalia, the Ogaden in Ethiopia and the North Eastern Province in Kenya. During the colonial period Djibouti was controlled by France and known as French Somaliland, Somaliland was BritishSomaliland, and Somalia was Italian Somaliland. The Ogaden was variously controlled by Ethiopia, Italy and Britain, while the North Eastern Province, then known as the Northern Frontier District was split between Italy in the north and Britain in the south.

Prior to that, the Somali people had never had a united nation. They shared a common language and similar cultural practices but the idea of somaliweyn, or “Greater Somalia”, didn’t gain ground until the 20th century (with a little help from the British).

The concept of somaliweyn is simple, namely that all five Somali regions should be united into one single and independent nation. After gaining independence from the Europeans, British and Italian Somaliland united as the Somali Republic in 1960. Despite the local popularity of the somaliweyn idea, the Northeastern District became part of Kenya and the Ogaden returned to Ethiopia. French Somaliland gained independence later oni, although again there had been strong support for a union with the Somali Republic amongst the ethnically Somalicommunity.

So far the somaliweyn brigade had two out of five. Then, in 1969, the president of the Somali Republic was shot by his own bodyguards and a coup d’état brought Major General Mohamed Siad Barre into power. With the Cold War in full swing, Barre sided with the USSR. Industries (the very few that existed) were nationalized, literacy programs implemented and Marxist theories adapted to fit within the teachings of Islam.

In 1977 Barre ordered the invasion of the Ogaden, miscalculating that the Soviets would support his war of liberation. It backfired spectacularly and the Soviets and Cubans deployed troops and advisers to help Ethiopia and fight back against Somalia.Knowing that his country’s location was of strategic significance to the players of the Cold War, Barre began courting the Americans, who were only too happy to become his allies.

Yet at home the defeat in the Ogaden led to disillusionment with both the government and the idea of somaliweyn. Opposition groups began to form, including the Somali National Movement, or SNM, that was dreamed up in London in 1981. Members came mostly from the Isaaq clan, which is concentrated in the north with cities of Hargeisa and Burao (the country’s second and third biggest after Mogadishu) being their main strongholds.

Clan is hugely important in Somali culture. Clan favouritism can permeate every aspect of life from securing jobs to getting married. Despite a tendency in the media to portray Somalia’s problems as religious-based, the origins of the civil war and even the trouble the area is experiencing today are very much rooted in this clan system.

Specific clans and sub-clans are concentrated in specific regions. The Darood dominates Kenya and Ethiopia’s Somali regions as well as Puntland. The Hawiye are centred around Mogadishu and much of the strip that separates the south from the north. The Raxanweyn come from Baidoa and stretch up to the border.

Knowing the importance of clans is essential for understanding what came next. As far as Barre was concerned, the SNM was an Isaaq organisation. Therefore, when he decided to attack the movement in 1988, he chose not to simply target individual members but the entire clan.

The force he brought down upon them was extreme. Hargeisa and Burao were flattened by bomber jets while state-sanctioned death squads terrorised nearby villages and buried the dead in mass graves.

Commanders actually filmed themselves issuing orders to massacre locals. “

The estimateof casualties ranges from 50,000 to 200,000, with an additional 400,000 people being displaced. SNM members and non-affiliated citizens alike were murdered, beaten, tortured and raped. Somaliland and Somalia were still united. Barre was doing this to his own people.

One of the strangest parts of what some have called a genocide against the Isaaq – although many other clans also suffered – was that is was all caught on video by the very people committing the acts. Hoping for a promotion back in Mogadishu, commanders actually filmed themselves issuing orders to massacre locals.

Somaliland declared its intention to secede in 1991. This had never been part of the SNM’s goals and not everyone came around to the idea immediately. It took several years for all the region’s clans to assent but the move did usher in a period of relative peace for Somaliland while things in the south went from bad to worse.

The word “Somalia” has become synonymous with danger, destruction and death. The civil war left as many as half a million people dead and the fighting never really ended. Clan-based factions now have to contend not just with each other but with Islamic militants, US air strikes and prolonged droughts.

Somaliland on the other hand has not had a terrorist attack since 2008. It has held several peaceful elections in which losing sides have handed over power. Knowing that in order to stand any chance at achieving recognition they need to be seen as stable and functioning, a lot of effort is put into trying to make the country accessible and safe.

That said, as much as the government and the country’s own citizens try to promote the image of Somaliland as a haven of peace and harmony, a little bit of perspective is necessary. Were the region to finally achieve independence, it would become the fourth poorest country in the world. The government budget works out at about 100USD per citizen per year. Around half the population is illiterate and almost every woman has undergone genital mutilation at the hands of their mothers and grandmothers. Little food is grown in the country and most of it is imported from Ethiopia and the UAE.

So what’s the upside between Somaliland and Somalia?

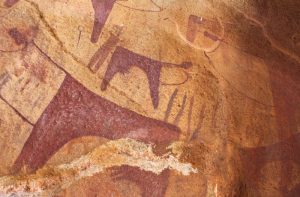

There are huge swathes of the country just waiting to be explored and documented. There’s not much information out there about Somaliland so if you’re looking for a place that is truly off the beaten track look no further. Generally speaking you can walk the streets without too much bother if you’re a guy or in a group. There is a small but lively diaspora and expat community. Visitors can see ancient cave art, try qaat and – if you’re lucky – even catch a glimpse of giant tortoises roaming the streets.

Of all the places your mother doesn’t want you to go, this one stands out for the openness of the people. Unlike North Korea or Turkmenistan, where discussing politics with locals is out of the question, people in Somaliland are more than happy to discuss current affairs. Similarly, the civil war isn’t some hushed up secret and most people are happy to answer questions about it.

It’s no paradise, but it’s not Somalia.

Guest Writer Bio

Callan Quinn is a journalist who has worked across four continents and lived in the UK, China, New Zealand, Australia and Somaliland. She is currently the editor-in-chief of Impact, the Hargeisa-based humanitarian and development magazine.