Welcome to part three of YPT’s far-too-long history of the Khmer Rouge. It’s been something of a personal project that’s ballooned out of all proportion, but ah well, that’s the fun of it! If you haven’t read the first and second parts, I’d encourage you to do so! Or don’t, it’s up to you. Part 1 is about context leading to their creation, part 2 is about the civil war. Here, we’re going to discuss what actually happened after the Khmer Rouge seized control of Democratic Kampuchea. Buckle up, this won’t be a very fun read.

Table of Contents

- Immediate Victory

- Old and New People in Democratic Kampuchea

- “Old” and “new” people differences

- Economy of Democratic Kampuchea

- The effects of banning money in Democratic Kampuchea

- Famine in Democratic Kampuchea

- Even cadres weren’t safe

- Genocide in Democratic Kampuchea AKA The Killing Fields

- The death toll

- The Road to the Collapse of Democratic Kampuchea

- The tables turned

- Vietnam Invades Democratic Kampuchea

Immediate Victory

So, on the 17th of April 1975, the Khmer Rouge won. Cambodia was renamed Democratic Kampuchea. There were still some battles to be fought, but these were mere stragglers. With no central government left, most either fled into exile or were killed outright, each stranded city was an island and was swiftly conquered or handed over peacefully. I’ve already mentioned the death march, but what else did the Khmer Rouge immediately do? Well… A good start was to shoot every member of government they could find, along with every military officer and in some cases, (particularly the infamous Northwestern Zone around Battambang province) every rank-and-file soldier. In Phnom Penh, captured figures of the old regime were marched to a sports stadium and executed. It was a chilling prelude of what was to follow across the nation.

One notable thing about the march out of the cities is that this necessarily meant the absolute and immediate end to all businesses present. But of course, you say! They’re communists! An end to businesses is natural! But you see, that’s not how it worked in pretty much any other revolution. If we’re to look at the early days of the USSR, businesses were primarily taken over by the state but even this was followed by the temporary ‘New Economic Policy’ that allowed a temporary return of capitalism while the new state developed itself to a point where it could take over. China pursued a similar model, not beginning its first five-year plan until four years after the founding of the country and taking somewhat longer still to complete the full nationalization of industry.

We’ll discuss the ideological implications of this in a later article, but for now it’s just important to note that industry and trade collapsed almost instantly, effectively cutting the throat of the economy it was supposed to inherit for Democratic Kampuchea. While the needs of agriculture and resettlement were indeed important, millions of urban dwelling Cambodians suddenly found themselves without jobs and forced into an environment they were unfamiliar with: forced to work in the fields. Now, let me ask you, reader. Are you a farmer? If someone put a gun to your back and marched you out into the fields right now and demanded you start making rice, how do you think you would cope? Well, this is where we get to the next part…

Old and New People in Democratic Kampuchea

In society, it’s pretty common to divide people into two categories. There may be many, but we like the duality: Yin and yang, good and evil, rich and poor, liberal and conservative, communist and capitalist, revolutionary and counter revolutionary. To the Khmer Rouge, this duality was expressed in the old and new, that being those who lived in Khmer Rouge territory before the final victory of the revolution and those who were forced out afterwards to Democratic Kampuchea.

Now, it didn’t matter that many of these ‘new people’ were in fact landless peasants and workers who were part of the socialist ‘base’, the fact is that they never fled to join the Khmer Rouge and had to be forced, so they were inherently untrustworthy. Not even communists were spared the judgement, with Phnom Penh’s sizable Chinese community having thousands of people from all walks of life, many influenced by China’s then-ongoing cultural revolution. They too were marched to the fields and further, were banned from speaking their language. For the Vietnamese, the vast majority were expelled from the country immediately, with the roughly ten thousand that remained soon subjected to a genocidal campaign that left few remaining.

“Old” and “new” people differences

Those from the cities gradually were spread out across the country, with a sizable chunk moving to the eastern zone which, as discussed earlier, was at least initially rather moderate. If one reads, for example, the autobiography of Haing S. Ngor, the academy award-winning actor who survived the Khmer Rouge and later played fellow Cambodian survivor Dith Pran in the movie The Killing Fields, he attests that the early days were not quite as brutal as they came to be. He worked on a co-operative farm where his treatment was roughly the same as that of the ‘old people’. When harvests were more plentiful and the Vietnam-inspired Khmer Rouge cadres were more amenable, one could almost come to believe that this ‘temporary hardship’ could be looked back on with less scrutiny. But in other zones, this was not so. In areas led by more hardline cadres and particularly where harvests were weaker, arbitrary punishment and execution ran rampant.

It was rare for ‘new people’ to have any choice in where they were relocated to throughout Democratic Kampuchea and when they arrived, rules were starkly different for them. The village co-operative was the new cornerstone of this peasant-led society. ‘Old People’ were regarded as full members of the co-operative while ‘new people’ were not. They were barred from positions of authority and denied rights in the (limited) democratic process. Indeed, even old people lacked many of these rights, as really, the hidden third class was that of the military and party cadre who were the only ones who truly took part in what few elections the new country had. A common internal saying regarding the new people was “To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss.” This pervasive attitude coupled with the aforementioned inability of many ‘new people’ to properly function in hard agricultural peasant life was a big part reason why sheer brutality was to soon follow, from being given lower food rations to worse accommodation and eventually, outright murder.

This immediate post-revolution was, however, a honeymoon period of sorts. As I said, the eastern zone wasn’t as bad. The problems truly began in September of 1975 when the decision was made to mass-relocate new people from these comparatively stable and prosperous areas to the Northern and Northwestern zones, areas much harder hit by hunger and where party cadres were considerably more brutal. An estimated 800,000 were relocated to the north-west alone, doubling its population and crippling its food supplies. The strain undoubtedly led to even further hostility from the old towards the new.

Economy of Democratic Kampuchea

One of the first things the Khmer Rouge did was ban money. Now, despite many thinking that this is the goal of communists, it’s really not– certainly not immediately. Socialists recognize that money serves a historical purpose and every socialist country–except for Democratic Kampuchea it seems– made use of money to organize the distribution of at least some goods. Even when food is given away for free and public utilities are a right, people may want to buy a little more or save up for something special! Given that Cambodia quite literally struggled to feed its people at this time, the collapse of money rapidly buried the ability for people to get things they actually needed. At least officially…

The effects of banning money in Democratic Kampuchea

You see, the thing about money is, you can’t really just ban it. Government money is just the best way to circulate it effectively and make sure the value of the note is what it says it is. But if you take money away, people just make their own, consider the cigarette economy of prisons for instance. What instead happened by banning paper currency is that people with savings had them wiped out, while those with goods became supreme.

Trading in gold and jewelry was particularly common in the early days of Democratic Kampuchea, while others traded in food or other goods, forming an underground black market where there truly never needed to be one. Countless people were doubtlessly murdered for the ‘crime’ of exchanging a currency just so that they could stay alive. What’s more, since cadres and soldiers were themselves lacking in ‘money’, bribery was still entirely possible with goods and services. This measure did nothing to solve rampant corruption throughout Democratic Kampuchea.

One thing you might know about socialist countries is their love of economic planning. The USSR had five-year plans, China had five-year plans, most of them did. In 1976, the Khmer Rouge announced their four year plan! Get it? It’s a year shorter because they’re so confident they can do it faster! And what’s more, they called it the Super Great Leap Forward. Y’know, like China’s Great Leap Forward, but better. This laughable display of national chauvinism was equally matched by unrealistic expectations. The stated aim was to double rice production by 1980 and export $1.4 billion worth of agricultural goods to purchase machinery to attain modern agriculture, then follow that up with modern industry within the next twenty years. This is relatively normal planning, but shockingly unrealistic for a nation reeling from civil war and presently on the brink of famine.

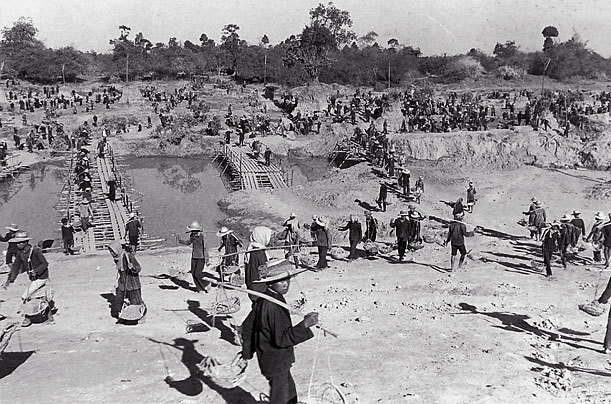

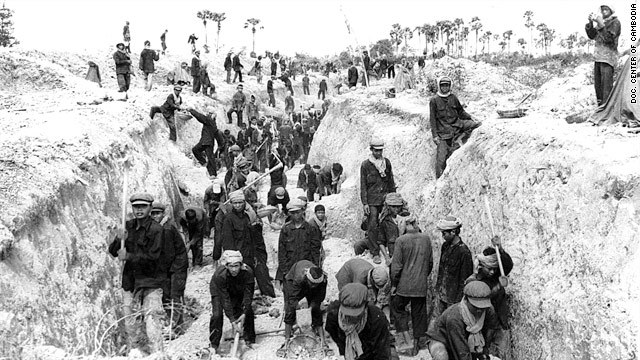

As discussed before, the northern and northwestern zones of Democratic Kampuchea were the destination of over a million ‘new people’. The reason is that these zones were the agricultural heart of Cambodia and, logically, more workers would mean more agricultural output, ergo more success in this economic plan. But here’s the thing, these people, again, knew fuck all about farming. The expectations placed on them were greater than anywhere else and more was expected to be seized from the area, quite literally taking food out of the mouths of the farmers who grew it. This is why things went… Poorly.

Famine in Democratic Kampuchea

The first harvest post-revolution was, reportedly… actually, not that bad. The second was an unmitigated disaster. Following the exodus to the northern zones, agriculture which was already precarious began to collapse and famine raged through these densely packed zones, further affecting other zones that may have relied on exports from these struggling regions, particularly as they struggled to meet their own quotas as well. To some degree, this failure had a degree of inevitability due to lack of foreign assistance, lack of machinery and the war-scarred nation that was still littered with US munitions. But the scale of the famine must be planted squarely at the feet of the Khmer Rouge leadership.

Even cadres weren’t safe

Contrary to how one might expect from a nation just setting itself up, the situation only got worse with time, not better. As the party center fought among itself and began mass-purging cadres believed to be too disloyal, such as those in the eastern-zone of Democratic Kampuchea which was practically a second civil war, brutality ramped up and expectations placed on the new people grew further and further outside of reality. The scale of this failure and brutality was a surprise even to many in the party higher-ups, with Ieng Thirith, the minister for social affairs, making an inspection tour of the north-west in 1977. It was noted by her that villagers were forced to march extremely far from their villages, in which they lacked actual homes and that the old, young, pregnant and infirm were all forced to participate. This ran contrary to Pol Pot’s own directives that such people not take part, but local cadre saw violence and coercion towards all as the only way to meet the impossible rice quotas.

Despite acknowledging failures, the party refused to recognize that the fault was theirs. Instead, the finger was pointed at ‘traitors.’ The full implications of this political failure will be discussed in another part, but its consequences were sharply noticed immediately. Rather than lightening the load of the workers, many among them were scrutinized and slaughtered for it. And then the eyes of the party turned on their own political cadre, accusing co-operative leaders of being traitors and hauling them off to the killing fields to be executed. This engendered a culture of fear among all sides, with brutality stepping up yet again as cadre feared what may become of them if they’re seen to fail their quotas. The party itself, while ironically positioning itself as all-seeing and all-knowing, was blind and dumb to the chaos they wrought.

The famine perpetuated itself as no real measures were taken to stop it. Famine weakens bodies who therefore can’t plant in the field. Starvation brought disease, which weakened bodies further, making it harder still to plant in the fields. Terror and violence naturally compounded. Even what little measures were taken were often counter-productive, like wasting countless man-hours of backbreaking labor to construct faulty irrigation dams which flooded fields and ruined arable land. The peasants involved were then, of course, blamed for failure to carry out the fundamentally flawed construction of the dam and executed as traitors, often after being tortured to reveal who ‘assisted’ them in their conspiracy, leading to further executions. Naturally, the loss of people to starvation and murder only left fewer hands to continue the desperately needed farming throughout Democratic Kampuchea

Genocide in Democratic Kampuchea AKA The Killing Fields

On top of famine in Democratic Kampuchea, brutality rocked the nation throughout the Khmer Rouge’s rule, only getting more severe as time went on. The demand for a mono-cultural Cambodian society saw the abolition of other languages and cultures, some of which were foreign visitors while others were native. Vietnamese and Chinese populations were variously forced to assimilate or were simply outright murdered. Buddhist monks, once a key source of support in the party’s 50s roots, were defrocked or massacred. The Cham Muslim minority were reportedly forced to eat pork or were killed, while their beards were cut, and their traditional way of life destroyed. Minority groups, largely, were no longer recognized and the choice was to join or perish.

The scale of massacre of these communities varied from time to time, but the overall effect was profound. The Chinese community alone, belonging to one of Democratic Kampuchea’s few allied nations, were reduced from 425,000 residents to 200,000 over the course of Khmer Rouge rule. Most fled, but many thousands were murdered. The ethno-nationalism of the Khmer Rouge saw even light-skinned Cambodians subject to severe discrimination, with the more dark-skinned northern Cambodian population seeing a comparably favorable situation.

More than anything, the victims of the Khmer Rouge genocide were those simply perceived to exist outside the strata of pro-Khmer Rouge rural peasants. The ‘old people’ and ‘new people’ distinction comes starkly back into contrast as even those ideologically and ethnically suitable Cambodians were still judged unworthy of life due to this distinction. While not the party’s official policy, many cadres simply looked for evidence of urban life as an excuse to murder. A Cambodian who could speak a foreign language almost by definition had received city education and thus was untrustworthy.

The death toll

An oft repeated claim is that those wearing glasses were executed as it’s believed glasses were a sign of higher education, which suggested being ‘new people’ and refusing to integrate with ‘old people’ customs. While this was not official party policy (with Pol Pot himself wearing glasses), it is likely that the feverish search for traitors saw peasant cadre making these assumptions and enacting such polices. Indeed, each ‘zone’ was often quite autonomous and carried out brutal initiatives of their own design. While the Khmer Rouge may not have specifically asked for it, their policy encouraged it.

Historian Ben Kiernan estimates that the death toll as a result of Khmer Rouge policy was between 1.671 million to 1.871 million, between 21% and 24% of the 1975 population. The true number is almost impossible to determine due to lack of record keeping, the chaos in the years prior to the revolution and refugees. All the same, the death toll is extraordinary, and some have estimated the number of deaths attributed to direct violence rather than famine could be as high as 60%. The infamous Cambodian ‘Killing Fields’ dot the country with over ten thousand mass graves known of.

The Road to the Collapse of Democratic Kampuchea

I don’t think you’ll be surprised to hear that the Khmer Rouge’s policies weren’t exactly popular. What’s more, ruling a nation by fear simply does not work in the long term. People simply do not tolerate it and indeed, the eastern zone is a great example of this. We’ve talked before about how the Eastern Zone was far more pro-Vietnamese and that the Khmer Rouge ultimately purged it of these elements over time. Through late 1977, remaining eastern zone troops and leaders waged a losing guerrilla struggle against the more hardline Khmer Rouge faction, with many more fleeing into neighboring Vietnam who had almost immediately become hostile to Democratic Kampuchea after its establishment. Towards the end of this year, Vietnam launched a punitive attack into Cambodian territory before quickly withdrawing, taking with them thousands of refugees.

The massacres in the Eastern Zone of Democratic Kampuchea intensified and while normal Khmer Rouge cadres typically wore red scarves as part of their uniform, all people in the Eastern Zone were instead made to wear blue scarves as an indicator, much like the yellow star forcibly work by Jewish people under Nazi rule. It’s believed that up to 250,000 were executed in this zone during the last six months of 1978 alone, further driving soldiers and Cambodian civilians into Vietnamese territory to stay alive.

The tables turned

In October of 1978, Khmer Rouge cadre Chea Sim led over 300 people into Vietnam. A subsequent Vietnamese attack and quick withdrawal provided an opportunity for Khmer Rouge cadre Heng Samrin to do the same, taking several thousand soldiers with him. These men were to form the nucleus of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (FUNSK in French acronym) which was formed on December 2nd of 1978 with an explicit goal of toppling the Khmer Rouge with Vietnamese assistance.

In an ironic way, the Khmer Rouge were correct about Vietnam being their greatest threat, but it was a threat of their own creation. Conflict with Vietnam began from the very start of the regime’s creation and military conflict was not far behind. With Pol Pot blaming Vietnam for the starvation and destruction wrecking the country, on the 18th of April 1978, he ordered a raid into the Vietnamese border town of Ba Chuc, which was to see the massacre of over 3000 villagers and only 2 survivors. Multiple attacks were conducted along the border, with the Cambodians retreating at the slightest Vietnamese military opposition, only to return as soon as troops had been withdrawn. Even after Vietnamese incursions into Democratic Kampuchea, where Democratic Kampuchea defenses were overrun, they returned to ‘fight back’ within a matter of days, seemingly oblivious (or at least the party was oblivious and demanded against soldier’s better judgement) to the overwhelming odds against them.

Vietnam Invades Democratic Kampuchea

Border skirmishes between Vietnam and Democratic Kampuchea intensified as 1978 wore on, with the start of December seeing added assistance from the newly formed FUNSK, who added legitimacy to the Vietnamese attack and softened Khmer Rouge claims of an imperialist assault on the nation. On the 25th of December, Christmas Day of 1978, Vietnam finally invaded in force despite threats from neighboring China and quickly began to overrun the Democratic Kampuchea forces.

The rapid Vietnamese gains were obvious. Vietnamese forces numbered 150,000; Cambodian soldiers numbered around 73,000. Vietnam had tanks and airplanes; Democratic Kampuchea had few of either. Vietnamese soldiers were well-fed and disciplined;, Khmer Rouge soldiers were starving and motivated far more out of fear than genuine loyalty. Within two weeks of standard warfare tactics, half of the Cambodian army had been either killed, captured or defected. A switch to guerrilla warfare protected more instant losses but had very little power in stopping the attack. The Democratic Kampuchea/Khmer Rouge government fled the capital and on January 7th, 1979, the Vietnamese captured it, declaring the People’s Republic of Kampuchea the following day and installing leaders of the FUNSK as its new leaders.

What remained of the Khmer Rouge fled across the border into Thailand, where they were granted asylum and allowed to set up ‘refugee camps’ along the border from which the Khmer Rouge would begin a renewed guerilla campaign that would last decades. Despite this, just as quickly as a few weeks, the Khmer Rouge had been all but wiped out as a political force, ending Democratic Kampuchea.

And that is that! Part 3 of this series of articles is done and this was a long one! That said, we still aren’t done, even after all this time… Next up, we’ll need to address what followed the demise of Democratic Kampuchea, as the Khmer Rouge certainly didn’t cease to exist… And then, we’ll cap it off with an analysis of their true politics to decide once and for all just what the fuck they actually were. Stay tuned for that next time!