Today (April 15th) marks the anniversary of the death of Pol Pot one of the most feared and ruthless leaders of the 20th century.

Table of Contents

- Biography of Pol Pot

- Democratic Kampuchea

- Why did the Khmer Rouge lose power?

- Khmer Rouge Insurgency

- Pol Pot and the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

- Pol Pot in Exile

- The trial of Pol Pot

- Death of Pol Pot

- The legacy of Pol Pot in Cambodia

Biography of Pol Pot

Pol Pot was born as Saloth Sar on the 19th of May 1925 to a prosperous farmer, and ended up attending some of the most elite schools in Cambodia, as well as studying in Paris, where he joined the French Communist Party and began his revolutionary “career”. After joining the FCP he was also to befriend a number of other Cambodian Communists, who would later be known as the Paris Clique, or Cercle Marxiste. Here they formed the Khmer Students Association, often seen as the first incarnation of what would later be known as the Khmer Rouge, complete with its reputation for absolute secrecy and indifference to Cambodian urbanization.

In 1953 he returned to Cambodia and initially became a teacher, before fleeing into the jungles and becoming part of the nascent Marxist-Leninist insurgency. He quickly became a senior member of what was then known as the Khmer Peoples Revolutionary Party. This would morph into the underground Workers Party of Kampuchea during a secret meeting 1960, although not with Pol Pot as leader.

In 1963 he became leader of the Workers Party of Kampuchea in somewhat dubious circumstances. The leader of the party at the time was Tou Samouth. In 1962 he was killed by government forces, although some have theorized that he was killed by Solath Sar and Nuon Chea in order to gain power of the WPK. On his death Nuon Chea in theory was to become leader, but instead pushed for Solath Sar/Pol Pot to take over, so as to appeal more to “intellectuals”. Upon Pol Pot’s rise to power, pro-Vietnamese elements began to be purged from the party.

It has been argued that Nuon Chea was the real power behind the throne through the rule of the Khmer Rouge, or that at the very least they ruled the country together.

There is a very interesting interview in which Nuon Chea discusses why he did not become leader of the Khmer Rouge.

Khmer Rouge Insurgency

In March of 1963, Sihanouk published a list of 34 Cambodian socialists, demanding they join the government with him. Pol Pot was on this list and was one of only two to ignore the summoning, while the remainder found themselves placed under permanent government surveillance, their revolutionary potential dead in the water. Recognizing that the cities were no longer safe, Pol Pot and many of his allies fled for Ratankiri province where they formed ties with an oppressed minority group there and benefitted from its border with Vietnam and Laos. Here, they formed a revolutionary base and shifted to insurgency.

As the neighbouring Vietnam war heated up, it was long known that Viet Cong forces were being armed by supply lines in Cambodia, known informally as the ‘Sihanouk trail’. After Richard Nixon’s election to US president in 1969, he ordered the covert mass carpet-bombing of neutral Cambodia to destroy the trail, dropping over 100,000 tons of explosives in just over a year from 1969 to 1970. The bombing devastated Cambodia and killed tens of thousands, but rather than destroying the Sihanouk trail, it galvanised support for the Khmer Rouge.

The Workers Party of Kampuchea thus began their insurgency in earnest, fighting not only the government, but the Khmer Bleu, whilst receiving support from both China and the USSR, though particularly from Vietnam, who maintained a somewhat uneasy alliance with the Cambodian rebels. Although they were a formidable fighting force, it was ironically the US backed coup in Cambodia that was to start their path to power.

Prince Sihanouk, despite being royalty, and therefore not all that communist, was a staunch ally of not just China, but also North Korea. In 1970, following his ousting, he flew to Beijing where he was convinced to form an alliance with the Khmer Rouge (now secretly known as the Communist Party of Kampuchea). And thus the seeds were sown for an all-out Cambodian Civil War and the fall of the Khmer Republic.

The Pol Pot – Sihanouk Alliance

Sihanouk formed a government in exile known as the Royal Government of the National Unity of Kampuchea (GRUNK), accompanied by the Khmer United National Front (FUNK). This coalition government had a mix of royalist, communist and other broad nationalist forces who opposed the US-backed coup of Lon Nol, with the FUNK ten-member politburo having four Khmer Rouge cadres. While all parties were theoretically equal, the Khmer Rouge had the most manpower, firepower and established bases, plus most of its leaders were in Cambodia while many other factions operated in exile. Gradually, the influence of non-Khmer Rouge forces waned.

This coalition ultimately resulted in many thousands of guerrillas fighting for the Khmer Rouge without knowing it. Certain provinces in Cambodia showed no sign of communist ideology and many peasants felt they were fighting for the return of the monarchy, only for Khmer Rouge forces to gradually replace their commanders and bring them to heel under Pol Pot’s control. Not that anyone knew who Pol Pot was, with his identity hidden and Khieu Samphan serving as ‘vice prime minister’ and ‘minister of defence’ for this theoretically royalist coalition government.

In response to the endlessly growing insurgency, the US government stepped up its bombing campaign and only drove even more people into the arms of the Khmer Rouge, further dwarfing their moderate counterparts. Not that everyone was worried about Khmer Rouge extremism at this time. Due to the influence of Vietnam, Khmer Rouge zones were nowhere near as violent as they later became. Only in isolated rural areas away from the Vietnamese border did Pol Pot proceed early with the mass collectivization of land and dismantling of old society.

In January 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, stipulating that Vietnam withdraw its forces and material support from Vietnam in return for US withdrawal from the Vietnam war. This justified the radical anti-Vietnamese views of the Pol Pot clique and saw a rapid escalation of repression in Khmer Rouge territory, with many pro-Vietnamese cadres purged outright. By this point the Khmer Rouge’s ranks had essentially replaced the minority factions of the Sihanouk alliance, only remaining in name to trick moderate Cambodians and the international community. Eventually, the Khmer Rouge dropped all pretence and went to war with their nominal allies, purging royalists.

Democratic Kampuchea

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge rolled victoriously into Phnom Penh, and initiated one of the most perverse interpretations of socialism that has ever existed. Initially though they were seen very much as liberators, with the ever popular Sihanouk as the titular head of state. Many people do not realise, but before Democratic Kampuchea was proclaimed, the Khmer Rouge refereed to themselves as “The Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea”. This led to the slightly perverse situation of an extremely orthodox communist regime, being led at least for a short time by a King.

Things though were to change extremely rapidly.

The whole population of Phnom Penh and all other major cities were emptied and sent to the countryside to work in communes. Lots has been hypothesized about why the Khmer Rouge did this but it can be very easily explained. Pol Pot wanted the country to enter into a “Super Great Leap Forward“. This would involve the country growing and selling a bumper harvest of rice, with the profits being used to industrialize the county and achieve communism in 4 years. Completely unrealistic and when combined with the paranoia and excesses of the regime, was to lead to one of the worst genocides in history.

Why then did the Killing Field happen, and quite how much can be blamed on Pol Pot? It would be very easy to see Pol Pot (the leader) as solely to blame, as well as the personification of evil, but there were in fact many moving cogs that drove the country into disaster. It should be remembered that the Standing Committee of the CPK remained almost unchanged from the inception of the party right into the 90’s.

Pol Pot though was the ideologue who had driven most of the policies of Democratic Kampuchea. In this respects it should be noted that neither Pol Pot, nor Angkar set out to kill people en masse, and technically at least had a theory. This was to turn the country into a communist utopia. Of course having the best intentions far from absolves them from blame on the matter.

When you combine the craziness of the plan, and the paranoia of the regime with the Ultra-Khmer nationalism, then Pol Pot was as the leader held ultimate responsibility for the disaster that befell Cambodia.

Of the millions who died of course it should be remembered that not all were simply executed, many died due to overwork, or famine. The end result though was 1.7-2.2 million of a country of 7.7 million dying. So, the question of “how many people did the Khmer Rouge kill” becomes moot. The clique undoubtedly caused one of the worst atrocities in history, whether they planned to, or not.

And the history is oh so recent. For those who visit Cambodia seeing S-21, or Choeung Ek Killing Fields are honest stark reminders of just how bad Cambodia’s oh sop recent past was.

Why did the Khmer Rouge lose power?

The Khmer Rouge were driven away from power by defectors from the party and their Vietnamese allies in 1979, but why did the Khmer Rouge lose power less than 4 years after gaining it? There are numerous reasons, which we will detail in a following link, but it can also be summarized quite easily. Democratic Kampuchea literally starved and terrorized its working and fighting force, whilst simultaneously trying to foment war with Vietnam.

Due to their backing from China the leadership of Democratic Kampuchea felt that they would support them in any war against the Soviet backed Vietnamese. Yet China under Deng was not the same country as it was under Mao. The Chinese tried to convince the leadership to negotiate with the Vietnamese, which due to their arrogance and to their detriment they refused to do.

China would later invade Vietnam in a punitive attack after the Khmer Rouge lost power in 1979, but they were in reality never going to risk all out nuclear war with the Soviet Union over Cambodia. You can read about the Sino-Vietnamese war here.

Thus when a combined Vietnamese and Cambodian force entered, they faced minimal resistance. Rather than being seen as invaders, they were by and large seen as liberators, or at the very least the lesser of two evils.. Ironically if Pol Pot and his clique had been slightly less arrogant and negotiated with the Vietnamese, they would not only have survived, but would have received western backing.

In any other scenario this should have meant Pol Pot and his cronies disappearing into exile, or better still facing trial for their crimes. These though were far from normal times and the Khmer Rouge, and the ever suffering people of Cambodia were about to become Cold War pawns.

Khmer Rouge Insurgency

Alas this was not to be the end of the Khmer Rouge. In one of the most shameful episodes of western diplomacy, the genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge were allowed to not only keep their seat in the UN, but had the western world helping to finance further civil war in a country that had already suffered so much. Imagine if this had been done with Hitler for example? Sounds silly, but the comparison is sadly extremely apt.

The insurgency was to get even weirder still when deposed King Sihanouk once again got into bed with the Khmer Rouge in an unholy alliance. This led to the perverse case of the legitimate government only being recognized by the Soviet Bloc, whilst the genocidal opposition maintained international recognition from the majority of the world. There are obviously myriad reasons about how wrong this was, but one of the main ones was that the already suffering Cambodian people were essentially cut off from aid from the western world.

Interestingly North Korea, despite being communist and part of the Soviet Bloc, supported neither the government, nor the Khmer Rouge, but specifically Sihanouk. Sihanouk and President Kim Il-Sung being extremely good friends.

Kim Il-Sung was to state;

“our Communism is not honourable unless it supports the patriots like Sihanouk, who struggle for the independence of their country and his people’s freedom. Communism would lose much of its value if it did not respect the patriotism and ideals of independence and freedom of others”.

President Kim Il-Sung on supporting King Sihanouk against the Soviet backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea

Pol Pot and the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

Officially at least they formed the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, led by Sihanouk (again) and with other non-communist parts to the coalition. The stark reality though was that with by far the strongest fighting force the Khmer Rouge were still very much in charge.

During this time Pol Pot officially at least stepped down from power. The party changed its name to the Party of Democratic Kampuchea, and began espousing Democratic Socialism. History has taught us though that their rhetoric changed very little in the areas they controlled and there were mass executions way into the 90’s. Although economically, things had changed greatly, with the Khmer Rouge calling for independent capitalist development in their territories rather than continuing the disastrous agricultural policies of the 70s.

A peace process was eventually started in 1991, which involved all of the main players, including the Khmer Rouge. They not only took part in peace negotiations, but were being wined and dined by world leaders like true statesmen.

The peace process involved a lot of good will from all sides and despite their crimes the Khmer Rouge were treated largely as equals, seen as essential for the country achieving peace. In the only such instance in history the UN came in to govern the country and set the scene for elections in 1993. UNTAC duly came into the country with the remit to disarm all groups, something they famously failed to do with the Khmer Rouge. This failure would prolong the civil war in Cambodia and the demise of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge for a further 5 years.

Pol Pot in Exile

For reasons unknown the Party of Democratic Kampuchea, now known as the Cambodian National Unity Party decided to boycott elections. And not only boycott them, but essentially turn the 6% of the country, or so they governed into the last Khmer Rouge state.

Despite boycotting the elections they remained important politically and were not even declared an illegal operation until 1996, largely due to their former royalist allies FUNCINPEC, but the tide was undoubtedly turning in a country now sick of war. Defections from the Khmer Rouge were openly courted and the movement descended into turmoil.. In this respects the CPP and their win-win policy was much more successful than the UN had ever been.

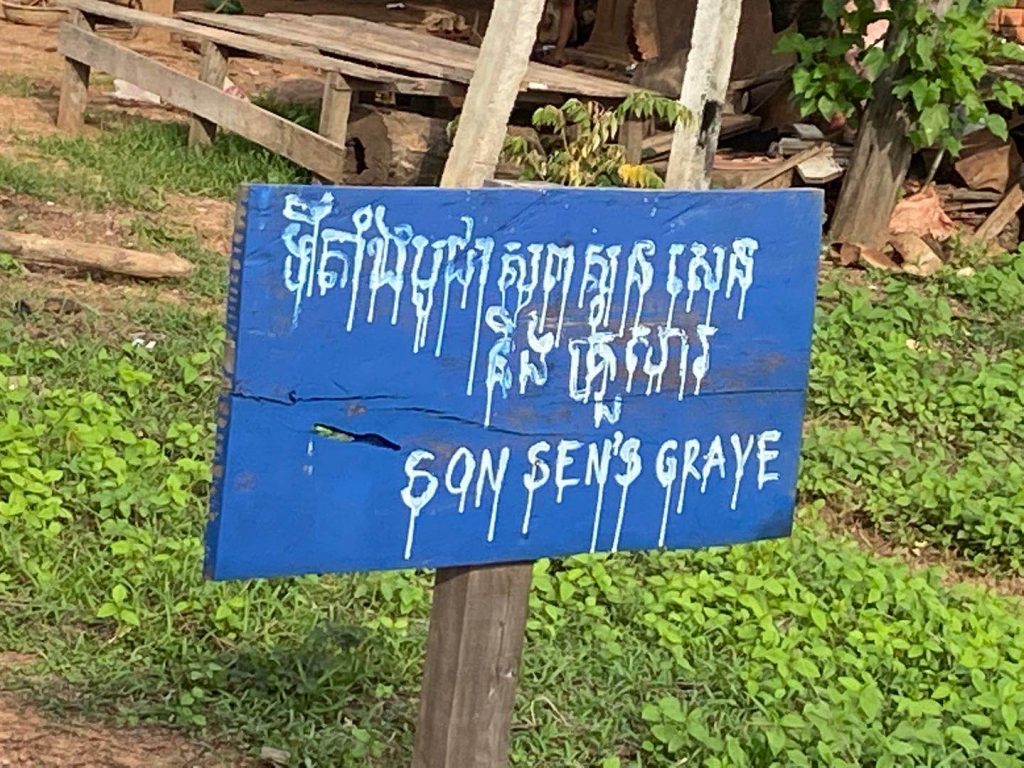

After various power struggles, defections, and assassinations within the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot was eventually removed from leadership of Angkar – in a spat with Son Sen and Ta Mok, both of which he had ordered to be killed. Son Sen was killed in spectacular fashion alongside his family. Ta Mok was not, and was to take over the leadership of the Khmer Rouge rump state in Anlong Veng with Pol Pot placed under “house arrest”.

To read about Anlong Veng click here.

The trial of Pol Pot

It is often stated that Pol Pot never stood trial for his crimes, this is certainly true when it comes to the crimes perpetuated under the rule of the Khmer Rouge, but he did stand trial.

The People’s Revolutionary Tribunal was established in liberated Cambodia to try Pol Pot and Ieng Sary among others in absentia. Unsurprisingly they were found guilty. They were sentenced to death, which never happened and confiscation of property, which one assumes might have happened. Although they still controlled large swaths of the country at this point.

It was though the attempted assassination of Ta Mok that was to lead to the only “trial” he was to face in his lifetime. On June 12th after the botched attempt on the life of Ta Mok forces loyal to him captured Pol Pot and his family and they were placed under house arrest. The remaining members of the Khmer Rouge sided with Ta Mok.

In late July Pol Pot and three commanders that had remained loyal to him were put on trial, not for genocide, but for crimes against the party and the attempted assassination of Ta Mok. He was sentenced to “life imprisonment”, which actually meant house arrest, whilst his 3 cohorts were sentenced to death and duly killed. Why he was not killed is open to debate, but it is likely the Khmer Rouge still saw him as a bargaining chip who could be used in any eventual peace talks. Amazingly and despite having tried to have him killed it appears that Pol Pot and Ta Mok remained good friends.

Death of Pol Pot

Pol Pot died onn April 15th 1998, apparently in his sleep. His body was preserved with ice and formaldehyde so that his death could be verified by people, including journalists attending his funeral. Three days later, his body was cremated by his wife on a pyre of tires and rubbish, utilized in an ironically Buddhist ceremony. Democratic Kampuchea under his reign was not only notoriously atheist, but also treated adherents to Buddhism and Buddhism monks extremely badly.

When it comes to the Pol Pot death much has been speculated about how he actually died. It seems almost certain that he was initialy kept alive by Ta Mok as a future bargaining chip, so some have speculated that he killed himself. Others have even suggested murder, after all it is much easier to blame a dead person for everything that went wrong. In reality though it does not matter how Pol Pot died. The simple fact is that he died peacefully, unlike his millions of victims.

Ironically the only trial he stood as previously mentioned was a Khmer Rouge one, being accused of “party disloyalty”, rather than anything related to the horrors of Democratic Kampuchea.

Sadly even his death added further punishment to the Khmer people occurring on April 15th, Khmer New Year, the biggest holiday in the country. This means that at what is supposed to be the happiest time of the year in Cambodia, when families get together the ghost of Pol Pot still looms large.

The death of the hated despot though did not lead immediately to the end of the Khmer Rouge. Ta Mok took control of the organization and whilst most aspects were wound up in 1998, it was not until 1999 when he was captured that the last remnants of the group finally disappeared. Cambodia finally had some semblance of peace.

Since then and at least as of 2023 there has since been peace, something Khmer people now hold dearly. Democracy might be questioned in the country at times, but do not underestimate how much stability means to many in the developing world.

Pol Pot’s Communist Credentials

It’s very popular to say that Pol Pot was the most evil communist to ever life, but it begs the question of how exactly he was a communist. Certainly, he led a party that was communist in name, he would talk the talk on occasion and he aligned with a few other communist countries, but is this alone enough? Communism after all is more than an aesthetic and what you call yourself. The official name of Sri Lanka is the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, but people don’t tend to regard it as such. Identifying socialist countries can be a bit tricky.

So let’s examine. To begin with, Pol Pot developed the Communist Party of Kampuchea in complete secrecy, not only being a clandestine organization but not officially declaring itself a communist party at all. This isn’t totally uncalled for, as Lenin stated outright in his work What is to be Done that the administrative functions of a revolutionary party should be secret and selectively chosen for the security of the movement. This however only referred to its membership and function, not its political line and intents, something the Khmer Rouge deliberately obfuscated. It’s also worth noting that this secrecy continued until 1977, two years after the fall of the Cambodian government and the end of any need for secrecy.

By the time of the Phnom Penh’s seizure by the Khmer Rouge, the party reportedly had about 14,000 members nationwide, an absolute joke for a country of around 7.5 million people at this time. New members were not even considered for years and whole communes would be without party branches. Much authority was vested in the army to carry out orders and impose them on the peasants, training them only in obedience rather than revolutionary politics. This policy is much more akin to Blanquism, a bourgeois ‘revolutionary’ philosophy which saw socialism imposed by a clandestine group through dictatorship without a mass movement.

For all the talk of Pol Pot being a ‘Maoist’, the Khmer Rouge utterly ignored the concept of the mass line espoused by Mao, in which the party cadres go to the masses to learn from them, what their needs and desires are, then develop those ideas from the masses through a Marxist framework and bring it back to them. The commandism of the party is something Mao explicitly denounced, recognising that without the masses understanding the purpose of their work and how it benefits them, they cannot be expected to support the party or the process of socialist construction at all.

Indeed, Pol Pot cared little about the support of the masses. Those who remained in the cities until the fall of Phnom Penh were regarded as inherently untrustworthy and barred from political participation, regarded with contempt as seen through the slogan “To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss.” These ‘new people’ as they were called represented a sizeable chunk of the Cambodian population and most of its intellectuals and professionals. While Mao urged for the unity of as much of the masses as possible, it seemed the Khmer Rouge wished for the dictatorship of the few. The concept of the proletarian class as revolutionary was ignored, with all revolutionary potential vested in the party core.

What more needs to be said? Perhaps the fact that the party was fundamentally racist and chauvinist, repeatedly stressing the lack of historical precedent for their revolution and the unique ability of Cambodia to surpass China’s great leap forward with the SUPER great leap forward (already thoroughly addressed as fundamentally capitalist here) Vietnamese people were often slaughtered, along with Cambodian ethnic and cultural minorities such as the Cham Muslims. Even the party’s opposition to capitalism seemed more born out of a feeling that it was imposed by foreign powers and that socialism granted Cambodia the power to be self-sufficient. For all the talk of socialism, socialist theory and the works of Marx, Lenin or Mao were rarely mentioned.

When the gang of four was arrested in China in 1976 and the cultural revolution was reversed by Deng Xiaoping, beginning China’s rapid transition into open capitalism, Pol Pot was quick to visit China and offer his praises for the new regime and the ending of what many pundits called his greatest inspiration. Knowing what we do now about the commandism of the party and the bourgeois nationalist purposes of the Khmer Rouge’s rice-for-cash economic plan, it’s not terribly surprising. And indeed, once Vietnam invaded and Pol Pot became an unlikely US ally, it’s not surprising that socialism was almost immediately de-emphasized in favour of anti-Vietnamese Khmer nationalism. It’s hard to see what about any of this is communist.

The legacy of The Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia

When you look at other genocides that have occurred, such as the holocaust, or even Armenia, people are still trying to grapple with them generations afterwards. What happened during the Killing Fields has not yet been generations. Almost everyone you meet is a descendant of either a collaborator, or as is mostly he case a survivor.

What occurred in Cambodia over that period is still too recent for the population, and it is impossible to meet any Khmer person who wasn’t affected in some way by the Pol Pot regime. Every Cambodian I have met has spoken about losing, usually multiple people to the regime. I know of one girl whose mother lost 8/11 siblings. In some respects the spectre of Pol Pot has meant the country having a collective form of PTSD.

I remember speaking with a Cambodian friend and we got to talking about the Khmer Rouge period, and he passed in comment that Pol Pot had shot his grandfather, not literally of course, but the regime. But to Cambodians they see no difference – Pol Pot was the maker of this suffering.

Another extremely key, but saddening legacy that Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge have left in Cambodia has been with regards to minefields, largely made up of anti-personnel mines. These so called “silent soldiers” still kill people every year. Only this year 3 de-miners were killed after trying to defuse 4 mines stacked one atop the other. And now despite the conflict having ended over 25 years ago Cambodia remains one of the 3 most mined countries on earth.

Thus whilst the anniversary of the death of Pol Pot is not something people celebrate, particularly with it falling on Khmer New Year. In fact and at least as of 2023 the death of Pol Pot is hardly mentioned, with people preferring to water fight instead. Some might say it is bad that his name, or death are rarely mentioned, but to Khmer that is the ultimate offense, they have moved on from his muderous regime.

If you’d like to learn more about the history of Cambodia join us on the Cambodian Dark Tourism Tour.