It’s no secret that the USSR wasn’t exactly a bastion of human rights. Show trials and executions, the mass deportation of political prisoners and the practice of “unpersoning” undesirables – executing them and then effectively erasing them from history – were all common, particularly under Josef Stalin’s reign of terror.

Perhaps one of the worst examples of the Soviet authorities’ callous disregard for human rights was the Nazino Affair – an example of the regimes penchant for mass deportations of both political prisoners and petty criminals. Due to chronic mismanagement, malnourishment, adverse weather conditions and the sadism of the underequipped and untrained guards, over 4000 people were to perish over 5 weeks.

The agrarian masterplan: taming the Siberian wilderness

In February of 1993, the heads of the OGPU (the then-KGB) and the gulag prison system proposed a “masterplan” to Stalin: the forcible relocation of “settlers” to Siberia and Kazakhstan, where they would establish collectivist farms and quickly establish self-sufficiency.

The plan was lacking in some key areas: the proposed ‘settlers’ were to be people without much experience in agriculture, and there was an ongoing famine in the USSR that would hinder any attempts to establish land-cultivation projects. Despite this, Stalin gave it the go-ahead, because Stalin never OK’ed any dodgy initiatives.

The ‘settlers’

The masterplan was arguably less about establishing self-sustaining collective farms and more about getting rid of undesirables. After establishing a domestic passport system (a callback to a massively unpopular pre-USSR policy in Russia), the Soviet authorities begin weeding out “déclassé and other socially harmful elements”. This meant former capitalists, such as merchants and traders; peasants who had fled the countryside to escape the famine; kulaks (wealthier landowning peasants); petty criminals; and anybody else who didn’t fit the ideal Soviet mould.

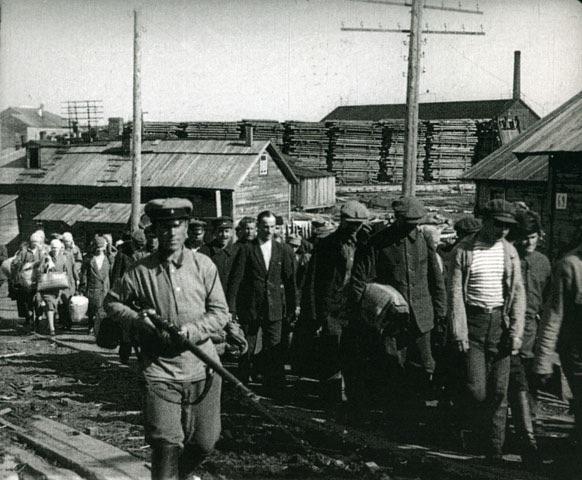

The deportation process

Rail convoys containing deportees set out from Leningrad and Moscow on April 29th and 30th respectively, and both arrived in Tomsk, Siberia, on May 10th. The deportees were each given 30 grammes of bread per day. The urban and peasant déclassé (e.g. those who had fallen in social status after the Bolsheviks took power) were repeatedly victimised by the criminals aboard the trains, who beat them and took their food rations and clothing.

Soviet officials in Tomsk, having no experience with urban deportees, expected them to be trouble and arranged for them to be shipped to more remote destinations. One of these destinations was Nazino Island, some 500 miles upriver from Tomsk.

The journey to Nazino Island

On May 14th, 5000 deportees were loaded onto timber-hauling barges and kept below decks. The authorities, perhaps feeling that the prisoners were getting fat and complacent on their 30 grammes of bread a day, reduced the ration to 20 grammes per day. The barges left with around 4 kilos of flour per person, and absolutely no other foodstuffs or cooking utensils. The guards sent with the deportees were newly recruited and lacked much in the way of uniforms, training or shoes.

Arrival at Nazino Island

Predictably, the unloading of starving and frightened people onto an isolated, swampy island with little in the way of supplies did not go well. 27 people had died in transit, and a third of the 6200 people sent there were unable to stand unaided.

Chaos erupted when the inexperienced guards tried to distribute flour to the deportees. Twice the guards attempted to unload the flour, and twice violent fights and shooting broke out. Eventually, a brigade system was worked out, where a single ‘brigadier’ per group of 150 people would go up and collect that group’s entire flour ration. These brigadiers were often criminals, and would inevitably abuse their positions.

Lacking anything in the way of cooking or food preparation utensils, the deportees had no way to prepare the flour. Most people simply put the flour in their hats and mixed it with untreated river water, which natural led to outbreaks of dysentery.

Desperate, many people began to build makeshift rafts to escape the island. Most of these crude rafts broke up and the deportees drowned; those that did manage to make it to shore were hunted and killed by the sadistic guards who awaited them. Even those who managed to survive these dual gauntlets had simply prolonged their suffering: all that awaited them was a lingering death from starvation and exposure in the unforgiving Siberian taiga.

The Soviet Lord of the Flies

Island society – if it can even be described as such –quickly broke down into a savage free-for-all. Most of the 6000-strong population of the island were city dwellers unschooled in basic agricultural techniques, and the deportees quickly formed into gangs. Vicious and lethal fights quickly broke out over what few resources there were, and people were murdered for the gold in their tooth fillings.

By late May, the food situation was desperate, and people were no longer being murdered for such useless trinkets as gold fillings. They were being butchered for their meat.

Termination of the initiative and relocation of the survivors

By early June, it was clear that the Nazino Island experiment was an abject failure. The authorities relocated 2,856 deportees to smaller settlements upstream. 157 deportees, unable to be moved due to having contracted infectious diseases, were left to die on the island.

In the five weeks since the deportees had left Moscow, between 1500 and 2000 had died due to malnourishment, disease, murder or accidental death. Another 2000 would never be accounted for, presumed dead in the Ob River or the wilderness of the taiga.

Unsurprisingly, given the horrors they’d endured on the island, most of the survivors refused to work at their new settlements.

A report by a local communist instructor, Vasily Velichko, highlighted the horrors of what the Nazino Island deportees suffered. The report was ultimately buried by Moscow, but beforehand the Nazino guard officers were arrested and sentenced to 1-3 years in prison. The affair also resulted in the termination of the quixotic resettlement plans, and urban déclassé were no longer shipped off to die horrific and bewildering deaths in Siberia.

See a nicer side of Siberia with our Buryatia/Lake Baikal tour this summer!