The Mongolians are historically a nation of nomads. This was true in Genghis Khan’s time, and it’s still true for 40% of the modern population.

But being a nomad does not exempt someone from the need for shelter – particularly with the harsh Mongolian winter and its biting insects of the summer – and that’s where the ger (pronounced like ‘gaire’) comes in. Designed to be cool in the summer and warm in the winter, these circular tents are easily collapsed and lightweight for transportation.

What’s with this ‘ger’ spelling? Isn’t it just a yurt?

Basically, yes. The only difference is linguistic – ‘yurt’ is Russian and ‘ger’ is Mongolian. There are different types of gers/yurts, which we’ll get into later.

A brief history of the Mongolian ger

As a nomadic people with a strong oral tradition, there isn’t much in the way of written evidence about how Mongolians lived pre-Genghis. This means that the origin of the ger is largely unknown.

The ger is chiefly used in Central Asia and is often seen as a unifying symbol of the “five ‘Stans” – Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – because of its prevalence there.

The Mongol Buryat people of southern Siberia lay claim to the invention of the ger, and the earliest depiction of one comes from a 600 BC bronze bowl unearthed in Iran.

Such was the breadth of the Mongol empire that the ger tradition survives in places you wouldn’t expect it at all – gers/yurts were commonplace in Romania until the 1970s!

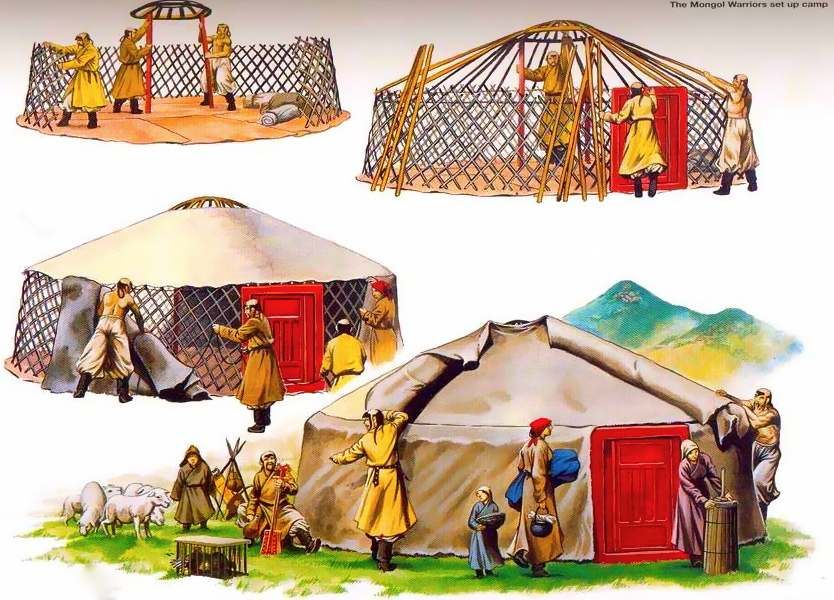

How to build a Mongolian ger

Gers/yurts are a product of their extreme environment. The Mongolian steppes offer little in the way of windbreaks or heat traps, and winds can gust up to 9km/h in spring. Throw in the extreme temperature variations 24° Celsius (75° Fahrenheit) to -28° Celsius (-19° Fahrenheit) and you find yourself needing shelter that can handle a whole lot of variables!

Yurts/gers are ideally suited to this inhospitable terrain. Their circular shape and aerodynamic roofs mean that they withstand the steppes’ strong winds, and their sturdy wooden doors – the weak point against strong gusts of wind – are sturdy and reinforced.

They also deal extremely well with both hot and cold temperatures. The fabric layers of the ger – traditionally felt, but many materials are used in this day and age – can be added or removed as desired, and the central stovepipe can be used to heat the ger in the winter. There’s also a crown opening that ensures air circulation and prevents it from getting too stuffy inside.

Erecting and dismantling a Monglian ger

One of the genius design features of the ger is its ease of construction and dismantlement. A ger can be erected in half an hour and dismantled in less than that. This enables nomadic families to follow their traditional pattern of upping sticks (quite literally) around four times a year, relocating to land more suited to the season and ensuring their livestock don’t overgraze the land.

A brief digression on the bentwood/Turkic yurt and Western yurt

The traditional Mongolian ger is not the only kind of yurt to be found. In Western Central Asia, where the weather is drier and more consistent, a taller, steeper kind of yurt is favoured using – you guessed it – bent wooden roof poles.

In the Western world yurts have caught on, but an awful ‘glamping’ way – such yurts are intended as semi-permanent luxury residences, built using hi-tech materials. In Europe the roofs are steeper and the materials more water-resistant due to the wetter climate.

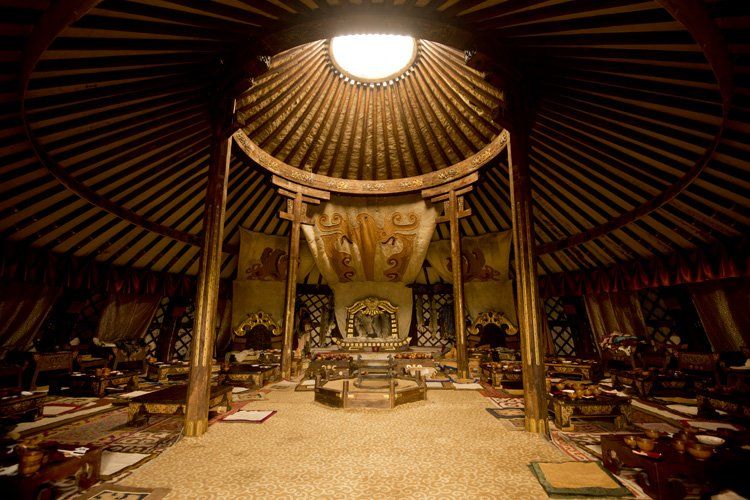

Who had the most badass ger in all of history?

Luckily we have an answer ready for your extremely specific question: of course it was none other than Genghis Khan, whose palatial ger was never dismantled and was moved in its entirety on a wheeled platform pulled by 22 oxen.

The largest ger today can be found in Turkmenistan, because of course it can.

Where should I try this ger thing out for myself?

You’d be remiss if you didn’t take to a ger/yurt in its ancestral homeland of Mongolia! Luckily we have just the trip for you, where you’ll spend not one but two nights in one!