In 2011, the first sparks of uprising were felt in Syria, soon to explode into an apocalyptic war of dozens of competing factions, ending hundreds of thousands of lives and eventually simmering down to a broken, fragmented country where the Syrian government controls the south, a Turkish-backed opposition controls the north-west and a completely different group controls the north-east.

That territory is now known by a number of different names, such as the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and of course Rojava. Sometimes called the only anarchist state in the world. So, how did all this happen?

Table of Contents

History of Rojava and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

Rojava Before the Civil War

On the 29th of January 2014, the ‘Charter of the Social Contract‘ was published by autonomist rebels, mostly Kurds among other minorities, which cited the regions of Afrin, Jazira and Kobane as the the new democratic, autonomous regions of Rojava. Unsurprisingly, these regions have always been the homeland of most of Syria’s Kurdish minority and have had their grievances with the Syrian government even before the Assad family came into power.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed after WW1, many newly independent minority groups found themselves spread out across various newly formed states. The Kurds were left without a country of their own, with attempts to form one in newly independent Turkey facing harsh pushback upon the rise of the Turkish Kemalists. A series of repressed rebellions soon led to a flood of refugees, with over 25,000 Kurds fleeing into what was then the French mandate of Syria. For a time, this seemed great. The French granted them citizenship, Kurdish nationalists began to get their voices heard, but in the end the French were only interested in helping up to a point. Soon, Syria became independent, under a new Damascus based government.

Kurdish culture and talk of independence soon started seeing greater and greater pushback. The rise of the 1958 ‘United Arab Republic’ in particular spelled a sharp reversal in fortunes for Kurdish people, as the Arab population of Syria rallied behind Egypt and Gamal Abdel Nasser to try the first attempt at a pan-Arab nation… Which was a problem for Kurds, because Kurds are not Arabs, do not speak Arabic and very often differed culturally, politically and even in terms of religion. Parties pushing for Kurdish rights were driven underground and even carrying Kurdish cultural books could be grounds for arrest. After the 1961 coup, Syria officially became an ‘Arab republic’ in a further blow to Kurdish autonomy.

The 23rd of August 1962 spelled the biggest surge in persecution as a census in Jazira stripped 120,000 Syrian Kurds (20% of all Syrian Kurds) of their basic citizenship on pretence of being Turkish illegal migrants. Even those with Syrian identity cards were stripped of them, as they were denied the right to work, education, healthcare, property ownership and political participation. Kurds began to face the worst of the Ba’athist government. In 1973, a strip of land 350km long and 15km wide along the Turkish border was emptied of Kurds and replaced with Arabs in yet another blow to Kurdish rights, with what remained of Kurdish land having the rights to non-Arab names restricted in 1977.

Hostilities simmered over the years. There would be occasional flare-ups of Kurdish culture only to be met by more harsh crackdowns. Since it was just the Kurds, who were faced by enemies on almost all sides, an uprising would have been doomed. After the collapse of the Saddam regime in Iraq in 2003, many persecuted Syrian Kurds simply uprooted and fled to the more secure and accepting Iraqi Kurdistan region, even further weakening what remained in Syria. It really seemed like for Syrian Kurds, there was just no option but to endure the abuse.

The Birth of Rojava/Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

The start of the Syrian civil war in 2011 saw chaos explode throughout the country. At first, Kurds didn’t seem to be a major force in the conflict.. This began to change after the murder of Mashaal Tammo, a Kurdish rights activist who had been controversial for his conciliatory attitude to the Syrian government. He never called for independence from Syria and simply wished for Kurds to have equal rights as citizens, yet he was gunned down in his home and when 50,000 marched at his funeral, the Syrian government opened fire killing five. The government under Assad attempted to placate by restoring citizenship to many Kurds, but it was too late. Patience was at its end.

Protests changed into armed uprisings and on the 12th of July 2012, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) formed the Kurdish Supreme Committee to administer Kurdish areas in what would soon become Rojava. To protect the region from the rapidly spiralling civil war, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) were formed, soon becoming one of the most effective armed groups in the whole conflict. By the 19th of July, the YPG had captured the city of Kobane, only to rapidly seize more cities as the Syrian army withdrew to fight elsewhere. In the chaos, the Kurdish territory had become one of the most easily liberated.

Transition to the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria/Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

The Kurdish Supreme Committee dissolved in 2013 as the PYD asserted itself as the predominant voice among the Kurdish autonomists, ultimately drafting and implementing the Charter of the Social Contract to form the autonomous region of Rojava. The PYD Kurdish authorities were very locally popular, but despised by many other anti-government rebel movements as well as by the government of neighbouring Turkey which had been fighting its own Kurdish insurgency for decades. Rojava found itself in a defensive battle against many different sides, soon to be overwhelmingly represented by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

The PYD led Kurds proved popular internationally, seen by many as the most ‘legitimate’ actor in the conflict, as the Syrian government and rebels were both widely accused of war crimes and sectarian massacres. Rojava, meanwhile, seemed to be a wholly innocent and progressive force that found itself besieged by one of the most vicious terror groups ever to exist. Even more eyes landed on Rojava as it built a reputation for accepting foreign volunteers, from European and American communists to hardened Kurdish guerrillas from Turkey who came to assist the war effort. After the successful defeat of ISIS in Kobane in 2015, Rojava formed an alliance with the US to better secure its safety.

The Syrian Democratic Forces and Rojava

On the 11th of October 2015, the Syrian Democratic Forces were established. It was recognized for quite some time that as powerful as the PYD and YPG were, they were a Kurdish group representing only Kurds, in a region that had many Arab, Turks and other minority groups. Gaining their trust (amidst many fears of Kurdish revenge and takeover) was paramount, especially with ISIS still a force to reckon with. Eight armed groups signed the SDF’s founding document and a few days later, the Syrian Democratic Council was established as the SDF’s political wing, established with the intent of representing multiple ethnic and interest groups in the region.

By March of 2016, Kurdish representation in the SDF had dropped to 60%. Still significant, but a clear show of their commitment to plurality, at a time when many other groups were highly exclusionary. With tens of thousands of fighters, it rapidly eclipsed ISIS as the largest and most effective rebel group, buoyed by backing from America and strings of military victories as the caliphate crumbled. With the exception of territory held by ISIS, Rojava came to consist of almost all Syrian territory north of the Euphrates river. Territory began to expand westward as the SDF assaulted the ISIS capital of Raqqa, finally seizing it on the 17th of October, 2017.

Not all was going well though. As was so often the case for the Kurdish people, Turkey posed a problem. In the midst of Rojava’s attempt to fight off the scourge of ISIS, on the 20th January 2018, Turkey attacked the SDF held city of Afrin near their border and seized it, with around 100,000 civilians displaced. Turkey would repeatedly strike at Kurdish territory while the Kurds in turn conducted guerrilla warfare against the Turks, essentially spilling over the conflict between Turkey and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) into Syria. To prevent further bloodshed, the SDF did the unthinkable among Syrian opposition groups and made a deal with the Syrian government, who formed a buffer zone between the two.

On the 23rd of March 2019, it was the SDF who delivered the final crushing blow against ISIS in their tent city of Baghuz Fawqani. It seems though that with that success, Rojava was no longer of any interest to the US. Their promised support against for the fragile and besieged territory waned until in October of 2019, the American forces under Donald Trump abruptly left their stations in Rojava territory, clearing a path for a Turkish offensive several days later, earning both Turkey and the US significant international condemnation. A 32km deep and 444km long ‘safe zone’ was cleared out of northern Rojava along the Turkish border, with 300,000 displaced to make room for resettlement under Turkish control.

Seemingly in response, on the 13th of October 2019, another deal was struck with the Syrian government to allow their forces into several large Kurdish cities to prevent a possible Turkish invasion. Syrian (and Russian) troops once again formed a buffer against Turkey, while the Syrian and Rojava administrations tacitly tolerated each-other on joint patrols and administration. The ‘alliance’ has been uneven to say the least, with some SDF factions breaking off to continue fighting the government. Protests and occasional gun battles occur over these building tensions, but at least for now, this tacit alliance has maintained the most peaceful status quo since before the start of the war.

What’s Rojava Like?

Politics in Rojava

The charter for Rojava helped outline some of the immediate political policies, essentially dictated at this time by the PYD. From the outset, the Ba’athist Arab identity for Syria is challenged by the preamble mentioning Arabs, Kurds, Syriacs, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians and Chechens, asserting the pluralised ethnic identity of the new region. It then asserts Syria’s territorial integrity, not wanting outright secession from the country but rather a federalist system to allow for more autonomy. Interestingly, the document made a point of promoting equality for women, something none of the other Syrian factions were fighting for. Human rights in general are greatly promoted, using the international declaration of human rights as a model.

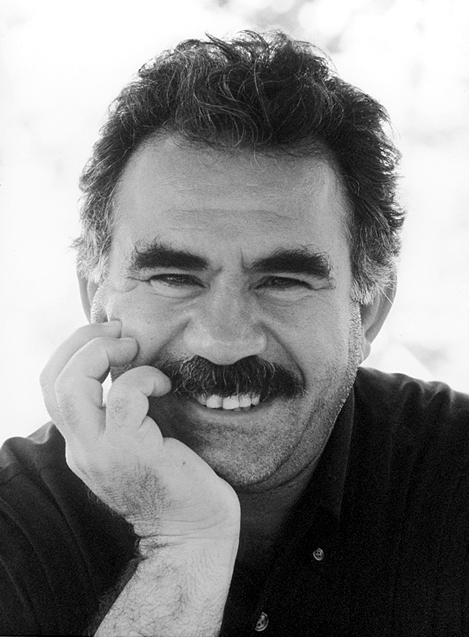

The political system for Rojava is known as democratic confederalism, a unique ideology developed by Abdullah Öcalan (Apo), the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) based in Turkey, which is often regarded as the PYD’s mother party. Inspired by the works of American political theorist Murray Bookchin, who promoted theories based heavily on anarchism, syndicalism, ecology and feminism. In Apo’s 2012 document on the subject, he described democratic confederalism as ‘democracy without a state’, which manifests in Rojava through the use of direct democratic communes and councils. The councils have membership scaled to the district’s population size, with 60% of council members elected directly, while the remaining 40% are elected by ‘groups and social segments’.

The different regions of Rojava (known as cantons) are administered largely independently and self-sustainably. The closest thing to an overarching government is the ‘Democratic People’s Conference, which follows the same 40-60 electoral rule as councils and involves the passing of legislation. This conference is led by a ‘presidency office’ consisting of two co-presidents and four deputies, with the co-presidents elected by absolute majority and deputies elected by 50+1%. Other political parties do exist in this system, though some have claimed that control is de-facto monopolised by the PYD, as suggested by the PYD-allied ‘Democratic Nation List’ coalition winning between 89-94% of each region in the 2017 elections.

Economy of Rojava/Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

As the economy of northern Syria had been left (arguably deliberately) underdeveloped by the Syrian government, the Rojava revolution saw to it that the economy oversaw a major transformation. Recognising its dependence on the wider Syrian government, there was a push to create a self-sustaining economy in the region, with state-run companies being expropriated and given over to the new governing councils. Land was redistributed to people that worked on it and worker co-operatives were set up to give workers more autonomy, pursuing a quasi-socialist project that got many leftists very excited. This said, capitalism was not being attacked, with the constitution enshrining private ownership and even foreign investment.

Co-operatives receive funding from from cantons as they see fit, while 30% of revenue from all co-operatives is distributed back into the canton fund to help spur healthy, democratic growth that isn’t just based on raw capitalist success. Despite this, the vast majority of workers are not in co-operatives and capitalism is still prevalent. The co-operative and communal systems are not imposed and capitalism is not explicitly opposed, rather Rojava sought to make capitalism function for the benefit of those living there. This has worked to a degree and indeed, wages in the region are much higher than in the rest of Syria, but due to hostility and embargo from Turkey, growth has been limited.

Society in Rojava/Democratic Federation of Northern Syria

Women in Rojava have an unprecedentedly large and important role in society when compared to the rest of Syria, likely boosted as a direct response to the simultaneous growth of the misogynistic Islamist groups such as ISIS and Al Nusra Front. The ideology behind this is known as ‘Jineology’, as described by Apo Ocalan, which asserts that the level of a society’s social transformation can be measured by the rights of its women. As a direct result, over 40% of Kurdish militias are made up of women, there is a 40% gender quota in in all political councils, ‘womens houses’ exist in every town and village for persecuted women and rights protect women from other forms of oppression.

The education system has been controversial among some for teaching students about the principles of the democratic confederalist system, as well as beliefs such as Jineology, criticised by some as political indoctrination, though this would be little different to the indoctrination seen in Ba’athist education systems or indeed the Islamic curriculum of many areas under rebel control. One notable gain has been the implementation of education in Kurdish and other languages, something barred under the Arabic-focused Ba’athist government. There are however some constraints as the Syrian government holds some influence over the curriculum (often being the authority paying public school teachers).

The circumstances of the Syrian civil war have birthed an entirely new system of government in the north-east. A system that has had to compromise with the hard reality of warfare and conflict with its neighbours, but has nonetheless thrived in its own way and provided an inspiration to many. How the project ultimately turns out is still something only time will tell, as various disputes both on the ground in Rojava and with the likes of Turkey and Syria still need to be resolved. All the same, what we have is a fascinating attempt to innovate in difficult circumstances and I have to say, it’s hard to really fault them.

What is it like to visit Rojava?

Visiting Rojava is no easy thing and requires lots of permissions from various government agencies. This can be very time consuming and bureaucrat and quite simply cannot be done interdependently. One can also not just travel to Rojava as a tourist, rather people come here either in a journalistic capacity, or as part of a social exchange.

Should though you manage to jump through these hoops then you will be in for a real treat, as not only are the Kurds and other people of Rojava very friendly but you will get to see just how exactly the current political experiment is going. ,

Things though are far from all good and certainly in places like Raqqa the shadow of the Islamic State regime weights heavy on the local people.

How can you travel to Rojava?

Previously this was all but impossible, but this has changed of late and it is now possible to arrange trips to Rojava that would start and finish in Erbil, Kurdistan. Currently it is not possible, or rather advisable to combine a Rojava Tour, with a trip yo Syria.

Young Pioneer Tours can currently arrange bespoke travel to Rojava, as well as journalist travel to Rojava. For more information get in touch, or check our Syria Tours page.