When people discuss the atrocities committed under communism, there’s one regime that’s uttered with particular revulsion, the Khmer Rouge. Between 1975 and 1979, a mere four years, the savage rule of Pol Pot saw anywhere up to two million dead, possible a quarter of the entire population of Cambodia. Life expectancy plummeted to the worst in the world and the legacy of genocide scarred the nation for decades after. If you want to convince someone that communism causes death and starvation, one need only look to the Khmer Rouge, right?

Well, almost. It’s unquestionable that the Khmer Rouge were a brutal regime and the term itself essentially means ‘Red Khmers’, with Khmers being the predominant ethnic group of Cambodia. Pretty explicitly linked to communism, don’t you think? Hell, they were in league with the north Vietnamese in their initial rise to power, we know for sure they were communists! It all seems cut and dry. Well, let’s dig into the long and complicated history and politics surrounding Pol Pot’s genocidal regime.

The Context of Cambodia

To understand the Khmer Rouge, you need to understand the context that they emerged from. Cambodia had, a very long time ago, been quite a mighty empire in the region. The Angkor Kingdom reigned supreme from the ninth to the fourteenth century, establishing some of the most fabulous palaces that still stand to this day in the form of Angkor Wat. This system, while mighty, was based off of oppressive social structures imported from neighboring Indian Hinduism which forced many Cambodian peasants into slavery. A mass conversion into Buddhism saw the emancipation of these peasants, but also the weakening of the kingdom.

This was followed by domination from both neighboring Thailand and especially Vietnam, which conquered Cambodia and whose legacy of colonialism was to weigh heavily on the Khmer Rouge’s mindset. What little remained of independent Cambodia was eventually forced by the colonial power of France to sign a ‘protection treaty’ in 1863, allowing King Norodom to maintain his throne. French control tightened with Norodom remaining as little more than a puppet ruler until the eventual military victory of France in October 1887 which led to the foundation of French Indochina. This territory consisted of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and a small portion of China, thereby linking the three nations under foreign occupation.

French colonialism was not equal and for many Cambodians, it was felt that Vietnamese domination had begun anew. France used Vietnamese administrators to handle Cambodian affairs and the capital of French Indochina was to be in Vietnam. Most public services were to be developed there while Cambodia languished primarily as a source of rubber plantations. Cambodia’s once great industries and irrigation fell into disuse and the nation began to rely on resources from its neighbors in the collective colony, as well as minimal help from France itself.

What later followed was imperialism from Japan in WW2, further crippling Cambodia and when the Japanese were driven out, the new puppet king Norodom Sihanouk felt little choice but to ‘invite’ the French back. As such, the domination of French Indochina continued, now under an even more capitalist model which saw many peasants indebted to landlords and moneylenders who more often than not were Chinese or Vietnamese, which was to be a major sore point for the Khmer Rouge in coming years. These painful conditions were ripe for Marxist revolution, which was indeed on the horizon throughout the entire region.

Early Cambodian Liberation Movements

Due to the political system of French Indochina, it was seen as prudent by the Comintern (Communist International, as led by the USSR) to push for the creation of a combined communist party across the region, rather than a scattering of isolated parties. The Indochinese Communist Party was thus formed on the 3rd of February 1930 as a combination of several existing parties in Vietnam. This was initially solely to be the Communist Party of Vietnam, but Soviet encouragement resulted in its control being expanded across all French Indochina. This party was led by Ho Chi Minh and even within Cambodia, most of its members were to be Vietnamese living in Cambodia. The result of this was to cement in the minds of many Cambodians that the Indochinese Communist Party was yet another organ of Vietnamese control.

On the 11th of November, 1945, the Indochinese Communist Party dissolved and efforts refocused on Vietnam. With Vietnam having the largest proletarian base when compared to the overwhelmingly peasant society of Cambodia, it was perhaps natural for a Marxist movement to be largest here. With a charismatic leader like Ho Chi Minh and a land border with the soon-to-be socialist China, it was Vietnam that was first to beat back the French and declare its independence in 1954.

What formed in Cambodia out of the dissolution of the Indochinese Communist Party was the Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party, existing largely as a side-project of the Vietnamese Communist Party and functioned as a united front which was to assist in its struggle for independence. A Vietnamese party document reportedly outright stated “The Vietnamese party reserves the right to supervise the activities of its brother parties in Cambodia and Laos.” With the ‘official’ Cambodian communist movement being so weak and subordinate to a neighbor that many Cambodians deeply distrusted or outright despised, far more began to flock to the Khmer Issarak, or the ‘Free Khmer’ movement which was a loose coalition of Cambodian independence guerrillas who followed a wide array of ideologies. The Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party was itself an Issarak group, with several more seeking the direct support of the Viet Minh.

1954 saw the Geneva Conference which officially made North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos independent nations. Some communists felt that they didn’t need to continue taking up arms due to their newfound independence, with King Norodom Sihanouk at the nation’s head. Many of the Issarak groups had been royalist from their inception and this loose, widely varying hodge-podge of ideologies was to be significant in the later development of the Khmer Rouge.

The Early Khmer Rouge

Some groups, however, chose to fight on. Communists who still wished to fight for Cambodia’s liberation received limited assistance from North Vietnam, with the United Issarak Front representing the largest faction of communist guerrillas left in the country. They were formed between the 15th and 17th of April, 1950, so at a time when Cambodia still was not independent. The United Issarak Front were pro-Viet Minh and a far cry from the Khmer Rouge. They held considerable sway over Cambodia’s left-wing Buddhists (with 105 delegates of their 200 member founding congress being monks) and their leader Son Ngoc Minh was widely praised. He himself founded what was at the time the Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party, which I mentioned earlier. While this nominally made the Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party the ‘head’ of the front, they were also aligned with non-communist groupings, some of which even consisting of royalists!

When Norodom Sihanouk successfully negotiated a settlement with France which kept communists out of power, many of those aligned with the United Issarak Front began to break away and reconcile with the government. Even worse, the negotiation included a withdrawal of Viet Minh forces from Cambodia, which many saw as a betrayal by their nominal Vietnamese allies. In the face of this, Son Ngoc Minh and about a quarter of the Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party ultimately left for North Vietnam to continue their work from there. The party subsequently retreated underground and a front group known as the Pracheachon was put forward to contest in legal elections.

The party in Cambodia was in turmoil and was eventually divided into two sections, the urban committee and the rural committee. The urban committee was led by Tou Samouth and was commonly regarded as being the ‘moderate’ faction, with closer links to Vietnam and a respect for Norodom Sihanouk as a legitimate Cambodian liberator. The rural faction meanwhile was headed by Sieu Heng and was far more skeptical of Vietnam, as well as being hostile to the ‘feudalist’ Sihanouk. Surprisingly, it was Tou Samouth who ultimately took Saloth Sar to be his protégé, the man who was later to become Pol Pot.

During the likely fraudulent elections of 1955, the Pracheachon was harassed relentlessly by the state and gained no seats. Rather, every single seat was taken by the pro-Sihanouk coalition party Sangkum. The illusion of democracy was shattered and worse still, Sieu Heng ultimately defected to the Sihanouk government in 1959, denounced his comrades and renounced communism. It’s been estimated that up to 90% of the rural party apparatus was wiped out in one fell swoop, cementing the control of the more moderate urban faction led by Tou Samouth.

The following year, between the 28th and 30th of September 1960, a meeting of what remained of the urban and rural sectors of the party met in an empty room at a Phnom Penh train station. Fourteen delegates represented the rural faction and seven represented the urban faction. The party was to be wholly restructured, with a new central committee formed with Tou Samouth as its first general secretary. Also a part of the central committee was Pol Pot, having rapidly risen through the ranks of the organization under his mentor. The party was also officially renamed, becoming the Workers Party of Kampuchea. Under the Khmer Rouge, the party’s former existence as the Cambodian People’s Revolutionary Party was to be entirely expunged from the official record, making the end of September 1960 the ‘official’ founding date of the party.

In June of 1962, the increasingly irrelevant Pracheachon front party tried to stand for elections again and this time were rounded up by force. The party was forcibly dissolved, with many figures being sentenced to death before subsequently being lowered to ‘mere’ life imprisonment. The political aspirations of the party were becoming increasingly remote, with the influence of the more militant faction becoming more prominent.

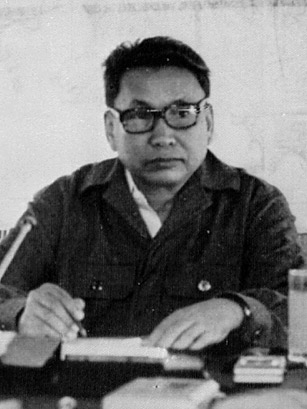

On the 20th of July 1962, Tou Samouth was killed by the Cambodian government, leaving the party without a leader. In February of 1963, a second party congress was held in which Pol Pot was elected as the head of the central committee. What’s more, several close allies of Tou Samouth were demoted and replaced by closer allies of Pol Pot, specifically many of those who were close to him during his time in Paris. A gradual restructuring of the party began, with those considered excessively pro-Vietnamese being gradually edged out of the party and replaced.

The Khmer Rouge Paris Student Group

There was a core clique forming within the Worker’s Party of Kampuchea that shared a common background. During the period of French occupation, Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan and Son Sen among numerous others were studying in Paris and united in the Khmer Student’s Association. All men were later to become high-ranking figures in the Khmer Rouge regime and their start was not in Cambodia at all, rather, it was in the student movement and the French communist party. It was here that their appetite for fierce Khmer nationalism began, as well as a strong distaste for the Viet Minh dominated factions of their homeland’s revolutionary movement.

A prominent attitude which was to continue into the Khmer Rouge was a desire for strong secrecy. The Khmer Student’s Association was to be infiltrated by the ‘Cercle Marxiste’, composed of cells of three to six that had little awareness of the overall organization. This made it hard for the French to stamp out and seemed like a proof of concept for strategies used later to keep the Workers Party of Kampuchea underground. Meanwhile, the members of the Paris group began developing their political understanding. Works written at this time showed a belief in a need for Cambodian self-sufficiency as well as opposition to the idea that industrialization and urbanization was necessary for national development. These concepts would raise quite a few skeptical eyebrows in mainstream Marxist circles, seeming almost antithetical to core Marxist and Leninist concepts.

Those who were a part of the Paris students group were primarily from privileged backgrounds and had comparatively little experience with the Cambodian peasantry that they wished to stand for. It is perhaps then unsurprising that their subsequent policies proved so disastrous when they wrested control away from much of the initial party leadership, implementing anti-Marxist methods and blinded by ultra nationalism… Though the explanation of that shall come a little later.

Shift to Insurgency

In March of 1963, what little remained of the above-ground socialist movement was destroyed, cementing Pol Pot and the Workers Party of Kampuchea as the only significant Marxist movement left. Norodom Sihanouk published a paper listing 34 prominent Cambodian leftists, demanding that they join the government. Sihanouk had made a habit of attacking communists and then inviting them into the government to serve as a front of alleged democracy, with their actual capacity in government being severely limited. On this list was Pol Pot. While other high-ranking members of the party had previously come to work with Sihanouk, Pol Pot distrusted his intentions and was one of only two to not attend the summoning demanded. Sure enough, every other person was forced to swear loyalty to Sihanouk and was then placed under 24 hour police surveillance, effectively destroying their capacity as opposition figures.

This was the final straw for the party and in July, Pol Pot and many others fled the capital to form an insurgent base in Ratankiri province, bordering both Laos and Vietnam. As the region was inhabited by an oppressed minority group, it served as a perfect breeding ground for guerrilla activity and by 1967, guerrilla attacks were being attempted on the Cambodian government. The following year, this shifted to a national insurgency which received the tacit backing of China and Vietnam, which helped to train and arm Cambodian guerrillas. This was largely kept a secret from the nominally allied government of Sihanouk, which had since 1965 been allowing Vietnamese forces to transport supplies through a route known as the Sihanouk Trail.

Things began to change in 1969 as American policy in Vietnam changed dramatically under recently elected president Richard Nixon. Sihanouk had always been a man playing a balancing act, preserving his nation’s neutrality by courting China on one hand and America on the other. Support to Vietnam was limited and existed only to prevent an assault he knew he had no chance of winning, but with American pressure mounting, he began a swing to the right-wing. Between March of 1969 and May of 1970, Operation Menu began, a covert bombing operation in which American bombers carpet-bombed the Sihanouk Trail. The operation was kept secret from all parties, including America and the American military itself due to its highly illegal nature. Sihanouk himself had never agreed to or been made aware of the operation, but had indicated to Americans prior that he would not necessarily oppose them chasing Vietnamese troops into Cambodian territory. Over a hundred thousand tons of explosives were dropped on Cambodia in complete secret.

In June of 1969, Sihanouk offered recognition to the south Vietnamese government. This coupled with the ongoing military attacks no-doubt swung Vietnamese opinions towards supporting the fledgling Khmer Rouge more closely. Even still, Sihanouk would not completely denounce the north Vietnamese and so his balancing act came on a narrower and narrower tightrope. In January of 1970, Sihanouk left Cambodia to visit France for several months, leaving prime minister Lon Nol in charge. During this time, riots began outside the north Vietnamese embassy demanding their withdrawal and when one of Sihanouk’s relatives was called up on corruption charges, they angrily demanded Lon Nol’s arrest. Seemingly seeing this as the final straw, troops loyal to Lon Nol arrested Sihanouk’s relative instead and the national assembly voted on March 18th to depose Sihanouk, granting Lon Nol emergency powers. What soon followed were massacres of Vietnamese living in the country, with the population of Vietnamese living in Cambodia dropping from 450,000 at the start of the coup to 140,000 five months later, most having fled while many others were killed. In response, Vietnamese forces stepped up military intervention in Cambodia, now actively seeking the government’s overthrow.

To Be Continued

And that is where we leave it now, with Sihanouk deposed, a new military dictator, thousands of civilians dead and the Khmer Rouge just a fringe little group active in a small province. This is the start of the Cambodian civil war, which was to last until April of 1975. The story of the Khmer Rouge is a long and complicated one, which I hope you’ve grasped the need for such elaborate explanations. Here’s Part 2! We’ll address the civil war era! Following that, we’ll take a look at the Khmer Rouge in power and what came after.