“It was a really bitter time, people nowadays wouldn’t believe it, it was so, so bitter,”said Lao Wu about his time in the Red Army, while eating a bowl of potato, carrot, tomato and rice that his wife had prepared for us.

Lao Wu, 86 years old, lives in the town of Anding in a typical ‘yaodong’ cave house. The couple have two rooms, both of which have a ‘kang’, a stone bed heated by a pipe. It’s connected with the stove where the day’s cooking is completed. Curtains shade the two doors leading into the house, brightly coloured patchwork made of material from old clothes, showing the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. Inside the house Lao Wu also has a telephone and a television, bought for him by his son. They’re the only electrical appliances in the house, but Lao Wu never watches television, because “it’s all rubbish.” Instead he spends his days alongside some of the other elderly men in the town, sitting on the side of the main street in Anding, where they smoke and watch the other residents going by. “Where are you going?” “I’m going down there to do something.” These are the kind of vague greetings that get passed around, greetings not meant to be answered with specifics.

When Lao Wu is not sitting watching the residents of the town go about their business, he is tending to the small plots of land outside his house. They are the only couple that live in this particular courtyard, which contains buildings that are slowly falling apart, buildings that have centuries of history. Within the courtyard Lao Wu and his wife grow potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, sweet potatoes and cabbage. The vegetables are enough to feed the couple for the entire year, with only rice, bread, oil and salt bought from outside. “We don’t want to grow more to sell, that’s way too much trouble because we would have to pay so much in tax,” explained Lao Wu. Half a dozen hens roam the courtyard, and will provide a hearty meal for when Lao Wu’s children arrive home for Chinese New Year in another month’s time.

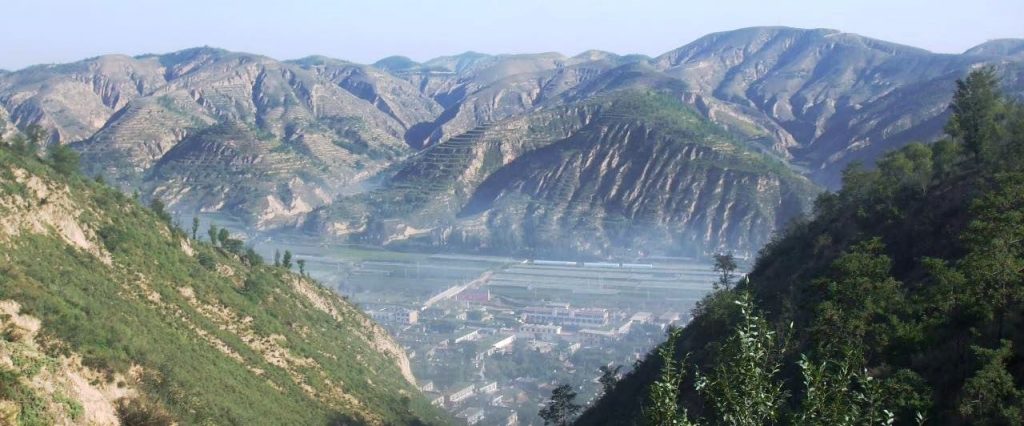

The town of Anding in northern Shaanxi province, north of the city of Yan’an, was part of the heartland of the Chinese Communist Party’s revolution. The nearby town of Wayaobao, now the county town of Zichang county, was the site of an important conference in 1935, presided over by Chairman Mao, when the decision was made to concentrate all efforts on defeating the Japanese imperialists, and to make the Communist Party a vehicle not just of the workers and peasants, but of the national and petit bourgeoisies too, a broader unity against the enemies of revolution, the landlords and the big capitalists, and the enemies of China – the Japanese Imperial Army. The importance of Wayaobao to the Chinese revolution inspires locals still today to refer to their county as Waguo, “Wa Country.”

Anding has been mainly gutted of its young adult population. The children remain for as long as they can stay in school, but their parents have mostly gone to the county town or further to find work. The fields are mainly farmed by people in their 40s or above, and most of the people in the age group 18-40 who remain are women, mothers looking after their children while their husbands go out to work elsewhere. Many of these women too have left, leaving the children in the care of grandparents. Anding is still home to many of this older generation, people who have experienced many of the changes of the 80 years or more of communist activity in the area, through the guerrilla period, the civil war, the liberation, the People’s Communes and the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the decollectivisation and market reforms after Deng Xiaoping took over, and the out-migration of the period of ‘development’ over the last few decades.

Lao Wu is part of this generation. He was born in 1929 and at the age of 17 joined the communists, becoming a messenger in the Eighth Route Army, the communist guerrilla army that was based in northern Shaanxi. “At the time, the Guomindang (Chinese Nationalist Party) came and occupied Wayaobao, the main town near here, but nobody would dare to join them. Even if we were going to starve to death we still wouldn’t join them! In Anding the communists had been organising for decades already, we knew about them and we respected them. They came through our town and talked with us. There were more than a few landlords in this area, but we were all so poor, we had little to eat. After the Japanese were defeated, we knew we had to defeat the Guomindang. It was that easy, so I decided to join the Eighth Route Army.”

Later, as the civil war intensified, battles were fought in the area, and earthen blocks were built along the ridges in the valley to allow communist snipers to fire at incoming Guomindang soldiers. The town of Wayaobao, and the county itself, had already been renamed Zichang by the communists in memory of Xie Zichang, the communist general and martyr who had died after being wounded in battle in 1935. When they pushed far enough down the valley to reach Xie Zichang’s hometown, near the town of Lijiacha, they discovered that the ‘feng shui’ of his village had been perfect for the birth of a hero. The hillside opposite resembled a dragon’s back, separated by the steady stream of a river. Fearing that this communist general’s influence lived on years after his death, and that the ‘feng shui’ continued to exert its pull, the Guomindang soldiers had destroyed part of the hillside hoping to destroy his posthumous influence on the civil war.

But even without the dragon’s back, by 1947 the Communists had routed the Guomindang in the valley and pushed them back out of Wayaobao, from where they retreated to Xi’an, the provincial capital over 300kms south. “After the Guomindang left we all felt elated. After all, this was our base, the base of our revolution. We followed Chairman Mao’s strategies – ‘when the enemy attacks we retreat, when the enemy retreats we attack’. Following these rules we easily beat them as they came down the valley past our town and further towards Lijiacha. After we chased them back to Wayaobao they dared not stay any longer and soon retreated all the way to Xi’an.”

By then the Eighth Route Army had been reorganised into the People’s Liberation Army.

“At that time I moved to Yan’an, which as you know was the capital of our revolution, where the Chairman was. But we didn’t stay long. We left our home and marched southwest where we liberated Baoji, in western Shaanxi. Then we marched northwest and liberated Lanzhou, in Gansu province. We were stationed in Lanzhou for the rest of the civil war and even after the liberation of 1949, when we pushed the Guomindang out of the mainland.

“How did I feel? Well, of course we were happy, we had won. But you can’t imagine how hard those times were. Our diet was so poor we mainly just ate millet. Have you ever eaten plain millet? Listen to me, you really don’t want to. We didn’t know what bread or rice was like in those days, let alone vegetables or meat. Sometimes we would only eat once every three days, and at the same time we might have to march vast distances, often at night. You know even these days people fall and die in the valleys around here, and at that time we marched in the pitch darkness on an empty stomach. I lost so many of my comrades, and not just in the fighting.”

After the establishment of ‘New China’, Lao Wu stayed in Lanzhou. The army helped in the reconstruction of war-torn China, especially after agriculture was collectivised in the early 1950s. “Of course, by that time we didn’t have to fight any more. We always stayed alert, especially after the Americans invaded Korea, but mainly our energy was spent in development. We went into the countryside and we helped with agricultural labour, but more importantly we dug irrigation ditches and canals, we made sure that our land could produce more food than ever before. In the army we started to eat better and feel content. I didn’t miss my home, I liked seeing new places, and we travelled all around northwest China. In 1959 there was an uprising in Tibet led by the Dalai Lama, we were sent from Lanzhou into Qinghai province to stop people from rebelling. We would walk for kilometres along mountain paths, so different from our mountains back home. They were green, and many of them were covered in snow. Our mountains back home, ha, only small shrubs can grow on that earth! But the Tibetan villages we passed through were all quiet, the trouble was mainly further south, and when the Dalai Lama fled they went west into India.”

But in 1960, after 14 years in the army, Lao Wu returned home to the yellow earth plateau of northern Shaanxi, back to Anding. “In 1960 my elder brother died, and so his wife and three sons had no means to support themselves. I had to return to raise them myself. In those days the farming was all collectivised, but I had to do my bit to get work points so that we could all eat. It was hard because I had to feed a lot of people. And I also got married at that time – my parents found a matchmaker who introduced my wife and me. At the time I was so nervous. You know I fought in battles and we marched for days on end without eating, but the day I went to meet my prospective wife I was more nervous than I had ever been in my entire life! We met with our parents and the matchmaker in the room as well, and the matchmaker began cursing me. She said, ‘look at you, you’re so thin, who would want to marry you!’ But we talked for over an hour and in that time everyone agreed with the match.” At this point Lao Wu’s wife shouted in from the other room, “you were so nervous you never said a thing,” to which Lao Wu reminded her, “and neither did you.” While many relationships in this county today are still done by ‘introduction’, at that time it was simply a matter for the parents, making sure the ‘astronomical suitability’ along with political background of the couple were a match.

Lao Wu worked in the collective fields to earn enough work points to keep his wife, along with his brother’s wife and their children, from going hungry. The women worked too, but earned fewer work points than the men. “The Great Leap Forward didn’t really affect us here. I remember people saying those three years were bitter, and the weather was so bad, but here the weather is bad every year, and we were bitter from work in the fields every year. I don’t remember many people dying, we were just very poor.” What about in the Cultural Revolution? “The Cultural Revolution, well, that was mainly some young folk creating disturbances. They would run around and they even bashed some heads off the statues in the temple near here, but other than that I don’t remember much. There were posters everywhere, of course, everyone wanted to air their opinions, and some local leaders were deposed.” What about education at that time? I know the primary school was already here. “Yes, the primary school was here, and more primary schools opened all around, in the villages along the valley and even up in the hills. In Anding the junior middle school also opened, but at that time we called it an Agricultural Institute. My children were all schooled there.”

During those years Lao Wu’s wife had given birth to five children, the first four being daughters and the last finally giving a son. The importance of a son was essential to the traditional culture, to the continuing of the lineage, a tradition that decades of communist propaganda – ‘women hold up half the sky’ – and years of Cultural Revolution – ‘destroy out-dated traditions’ – had failed to eradicate. After giving 14 years of his life to the army and the revolution, Lao Wu now receives 400 yuan a month, around £40, from the government. At over 80 years old he still has to grow his own vegetables, or the money will not be enough to live on. Their five children are therefore very important. “We have a daughter in this town, and another nearby. One is in Yongping in the next county, and one in Xianyang near Xi’an. We see our daughters who live nearby, but the ones outside of the county don’t come back regularly. Our son is working in Xi’an. He worked in Beijing before, something to do with electronics, and now he works in an office. He is busy, of course, so he only comes back for a few days at New Year. When will he come back this time? Who knows, we don’t even know what he’s doing. If we need any money he will give it to us, but we don’t really need any, we have enough for our lives.”

But Lao Wu is not discontent. “In the late 1970s we decollectivised and split the land into private plots. Did anyone oppose this move? Well, we didn’t have a choice. They’re the government, the Communist Party, they fought for us workers and peasants and without them who knows what it would be like. Now we have a government that looks after its people.” But didn’t you also just say Anding has hardly changed in these last two or three decades? “Yes, but that doesn’t matter, we’re content with our lives.” Unlike the younger generations, Lao Wu, along with many of his peers, feels no need to complain against his lot. As our conversation drew to a close we both munched our way through baked sweet potatoes before smoking one last cigarette. This old man has seen a lot, and a meal of rice and vegetables, with sweet potato for afters, is sure a change from a meal of millet every three days. After year upon year of working in the fields, the idea of not working hard and growing his own food, even at over 80 years old, is also a foreign concept for him. Lao Wu was a witness to the inequalities of his day and an actor in the efforts of men and women to change things, and as he reminded me as I walked out the door, “without the Communist Party there would be no New China!”

If you’re interested in meeting Lao Wu, or others with fascinating stories to tell, join us this November for our annual Revolutionary Tour of China. This tour takes you from the seat of Communist power Beijing to the ancient capital Xi’an, then north through Yan’an, to spend a night in a cave house and to meet with old Red Army veterans.